Colleagues say they knew Hardeep Singh Nijjar could be targeted by India for his role in Canada as a community leader

Sarah Berman in Surrey, British Columbia

Justin Trudeau may have shocked the world this week when he linked “agents of India” to the murder of a Canadian citizen in British Columbia, but colleagues who worked alongside Sikh leader Hardeep Singh Nijjar before he was shot dead this summer said the link was already clear.

“We’re not surprised,” said Gurkeerat Singh, a volunteer at the Surrey temple that Nijjar led from 2019 until his death on 18 June. “The whole community knew who was behind it. We knew that Hardeep Singh Nijjar could be targeted by the Indian state for his role as a community leader advocating for human rights and for a separate Sikh state.”

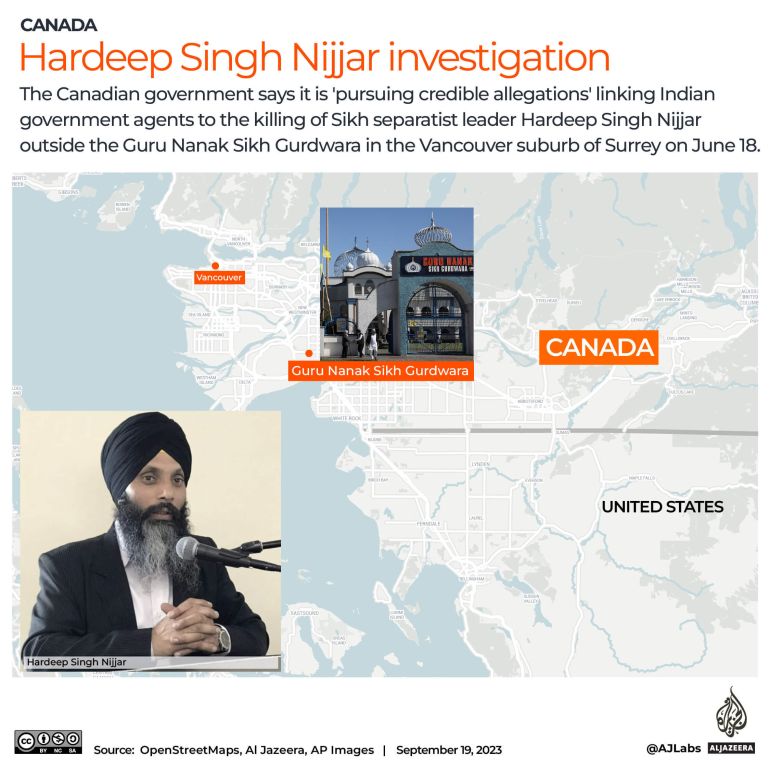

Surrey, British Columbia is a sprawling suburb outside Vancouver, hemmed in by highways to the east and west, the Fraser River to the north, and the United States border to the south. Since the 1980s the area has become a landing pad for many diasporic communities.

It is home to one of the largest Sikh communities outside of India, and the Guru Nanak Gurdwara – where Nijjar served as president – is a prominent global voice advocating for the creation of a Sikh homeland. But it also plays a key role in local life: every day the temple fills with hundreds of people seeking meals, disaster relief, and other kinds of aid.

Named after the religion’s founder, the temple sits on a deep lot behind blue and white pointed arches, with a silver dome and flagpoles rising above the front gates.

Worshippers at the gurdwara on Tuesday expressed overlapping relief, anger, hope and fear in reaction to Trudeau’s comments: relief that India’s alleged foreign interference was publicly named; anger that more wasn’t done to protect Nijjar; hope that Canada would take further action to hold perpetrators to account; and fear for personal safety as global tensions rise.

One temple volunteer, who asked not to be named, said that Canadian Sikhs with family in India were struggling.

“We are grateful somebody has finally stepped up and spoken for minorities in India,” she said. “Now obviously there are safety concerns. So, [for] Canadians that are going to be travelling to India, is it safe for us? Can we go? What’s going to happen if we go?”

On Tuesday, Canada issued new travel advice for India, warning of an increased threat of terror attacks in the country. On Wednesday, India followed suit, warning its nationals of “growing anti-India activities and politically condoned hate crimes” in Canada.

When Trudeau made his statement to parliament late on Monday, Nijjar’s supporters were set to gather for an evening prayer at the site of his assassination, a parking lot behind the gurdwara.

When the crowd started to gather on Monday night, news of the prime minister’s allegations had already filtered through the community. The prayer circle expanded to include performance, poetry reading, speeches and political organising.

“The way we deal with loss in our Sikh community is very different. Yes, there’s sadness,” Singh explained, “but if his sacrifice is what led to India’s hypocrisy and India’s brutality to be unmasked in front of the whole world, then his sacrifice is something to be celebrated.”

Three months after Nijjar’s death, no new president has replaced him. Volunteers who attended Monday’s gathering say there were both tears and smiles as the community celebrated its central pillar. Rows of yellow and blue Khalistani flags and a billboard bearing his likeness framed the scene.

“We feel like his spirit, his strength, is still among us,” Singh said.

Nijjar, who was born in Punjab, moved in the mid-90s to Canada, where he married, had two sons and opened a plumbing business. He was a naturalised Canadian citizen.

In 2020 Indian authorities accused Nijjar of belonging to a proscribed group and designated him as a “terrorist”. Last year, officials accused him of involvement in an alleged attack on a Hindu priest, and announced a cash reward for information leading to his arrest.

His colleagues remember him as a hard-working servant of his community, who would wake up before dawn to wash dishes or clean bathrooms before an early morning program at the temple. “He would be the first one to show up here and the last one to leave,” Singh recalled.

Sikh diaspora activism has long been a source of tension between India and Canada, with Delhi repeatedly accusing Ottawa of tolerating “terrorists and extremists”.

In the 1980s Sikh separatists were linked to attacks on India’s prime minister and Air India flight 182, which killed 329 people. Thousands of Sikhs were killed in retaliatory riots.

Gurkeerat Singh, 30, wasn’t born when these violent events took place, but he knows a “terrorist” stigma still lingers. Some Canadian Sikhs who oppose India’s crackdown on religious minorities don’t support an ethno-national solution, either.

Instead of silencing the separatists, Nijjar’s murder seems to be giving new life to the exiled political movement, he said.

The Guru Nanak temple’s walls are lined with posters asking members to vote “YES” for Punjabi independence.

“The Indian state might have thought that by killing one individual they might put a hold on this cause or put fear inside people,” Singh said. “For us, the people who were close to him, it gives us more inspiration.”

The temple hosted a non-binding separatist vote last month, and there are plans to host a second vote on 29 October. The Sikhs for Justice campaign, which has collected ballots in communities around the globe since 2021, aims to hold a vote in India by 2025.

Moninder Singh, spokesperson for the BC Sikh Gurdwara Council and a close friend of Nijjar, spoke to supporters in a video message on Monday.

“The underlying feeling is one of frustration and anger,” he said. “Nobody did anything for his protection. Nobody did anything to hold India accountable in any which way.”

Moninder Singh also raised concerns about ongoing intelligence sharing between Canada and India.

But amid the frustration, anger, and fears that another attack could follow, Singh said there was also a glimmer of hope. “Canada has never called India out like this before,” he said. “The people behind this attack on Canadian sovereignty should be held accountable no matter how high-ranking they are in the Indian government.”