AI’s flaws and dangers are glaring, yet the industry keeps growing, fueled by fantasies and fears of missing out (FOMO)

By Emily M. Bender & Alex Hanna ,

Truthout/Harper

August 16, 2025

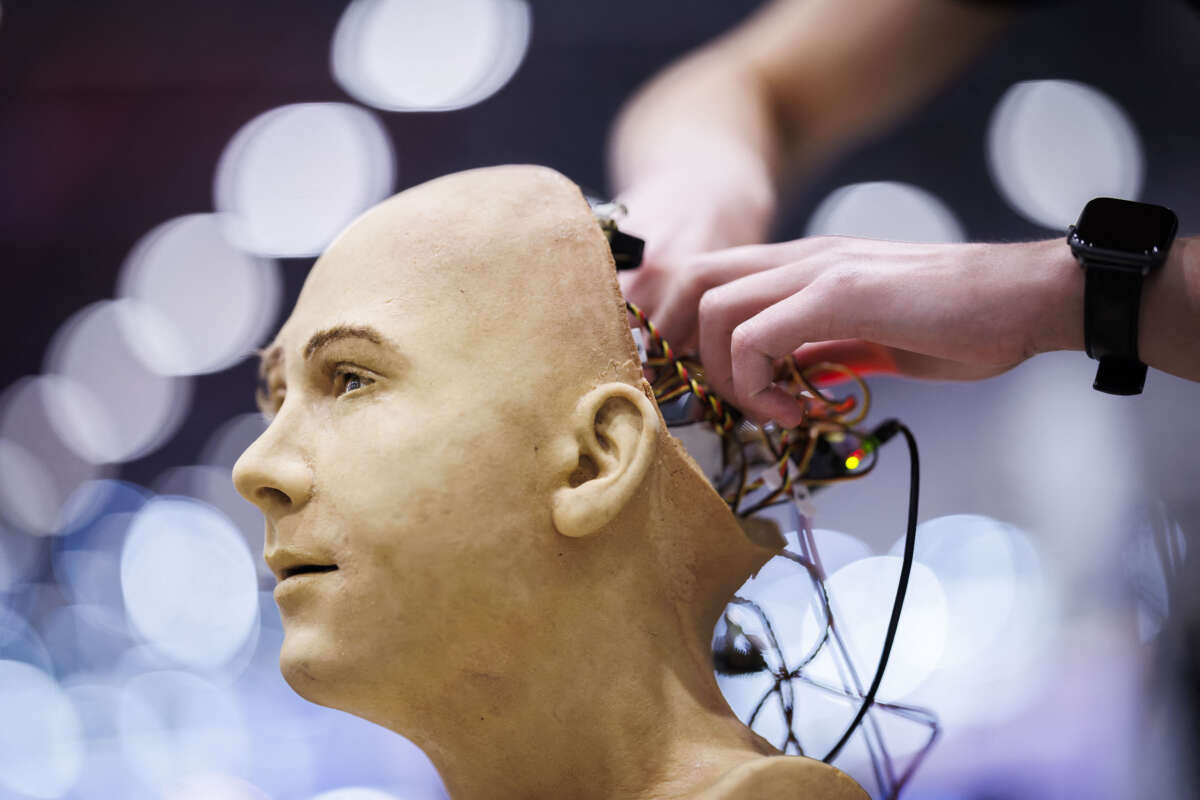

A man works on the electronics of Jules, a humanoid robot from Hanson Robotics that uses artificial intelligence, at a stand during the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) AI for Good Global Summit in Geneva, Switzerland, on July 8, 2025.

VALENTIN FLAURAUD / AFP via Getty Images

Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

This article is an excerpt adapted from the book The AI Con: How To Fight Big Tech’s Hype and Create the Future We Want by Emily M. Bender and Alex Hanna (Copyright © 2025 by Emily M. Bender and Alex Hanna). Reprinted courtesy of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

As long as there’s been research on AI, there’s been AI hype. In the most commonly told narrative about the research field’s development, mathematician John McCarthy and computer scientist Marvin Minsky organized a summer-long workshop in 1956 at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, to discuss a set of methods around “thinking machines”. The term “artificial intelligence” is attributed to McCarthy, who was trying to find a name suitable for a workshop that concerned a diverse set of existing knowledge communities. He was also trying to find a way to exclude Norbert Wiener — the pioneer of a proximate field, cybernetics, a field that has to do with communication and control of machines — due to personal differences.

The way the origin story is told, Minsky and McCarthy convened the two-month working group at Dartmouth, consisting of a group of ten mathematicians, physicists, and engineers, which would make “a significant advance” in this area of research. Just as it is today, the term “artificial intelligence” did not have much coherence. It did include something similar to today’s “neural networks” (also called “neuron nets” or “nerve nets” in those early documents), but also covered topics that included “automatic computers” and human-computer language interfaces (what we would today consider to be “programming languages”).

Fundamentally, the forerunners of this new field were concerned with translating dynamics of power and control into machine-readable formulations. McCarthy, Minsky, Herbert Simon (political scientist, economist, computer scientist, and eventual Nobel laureate), and Frank Rosenblatt (one of the originators of the “neural network” metaphor) were concerned with developing tools that could be used for the guidance of administrative — and ultimately— military systems. In an environment where the battle for American supremacy in the Cold War was being fought on all fronts — military, technological, engineering, and ideological — these men sought to gain favor and funding in the eyes of a defense apparatus trying to edge out the Soviets. They relied on huge claims with little to no empirical support, bad citation practices, and moving goalposts to justify their projects, which found purchase in Cold War America. These are the same set of practices that we see from today’s AI boosters, although they are now primarily chasing market valuations, in addition to government defense contracts.

The first move in the original AI hype playbook was foregrounding the fight with the Soviets. The second was to argue that computers were likely to match human capabilities by arguing that humans weren’t really all that complex. In 1956, Minsky claimed in an influential paper that “[h]uman beings are instances of certain kinds of very complicated machines.” If that were indeed the case, we could use more controllable electronic circuits in place of people in military and industrial contexts.

In the late 1960s, Joseph Weizenbaum, a German émigré, professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and contemporary of Minsky, was alarmed by how quickly people attributed agency to automated systems. Weizenbaum developed a chatbot called ELIZA, named for the working-class character in George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion who learns to mimic upperclass speech. ELIZA was designed to carry on a conversation in the style of a Rogerian psychotherapist; that is, the program primarily repeated what its users said, reframing their thoughts into questions. Weizenbaum used this form for ELIZA, not because he thought it would be useful as a therapist, but rather because it was a convenient setup for the chatbot: this kind of psychotherapy is one of the few conversational situations where it wouldn’t matter if the machine didn’t have access to other data about the world.

Despite its grave limitations, computer scientists used ELIZA to celebrate how thoroughly computers could replace human labor and heralded the entry into the artificial intelligence age. A shocked Weizenbaum spent the rest of his life as a critic of AI, noting that humans were not meat machines, while Minsky went on to found MIT’s AI laboratory and rake in funding from the Pentagon unhindered.

Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

This article is an excerpt adapted from the book The AI Con: How To Fight Big Tech’s Hype and Create the Future We Want by Emily M. Bender and Alex Hanna (Copyright © 2025 by Emily M. Bender and Alex Hanna). Reprinted courtesy of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

As long as there’s been research on AI, there’s been AI hype. In the most commonly told narrative about the research field’s development, mathematician John McCarthy and computer scientist Marvin Minsky organized a summer-long workshop in 1956 at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, to discuss a set of methods around “thinking machines”. The term “artificial intelligence” is attributed to McCarthy, who was trying to find a name suitable for a workshop that concerned a diverse set of existing knowledge communities. He was also trying to find a way to exclude Norbert Wiener — the pioneer of a proximate field, cybernetics, a field that has to do with communication and control of machines — due to personal differences.

The way the origin story is told, Minsky and McCarthy convened the two-month working group at Dartmouth, consisting of a group of ten mathematicians, physicists, and engineers, which would make “a significant advance” in this area of research. Just as it is today, the term “artificial intelligence” did not have much coherence. It did include something similar to today’s “neural networks” (also called “neuron nets” or “nerve nets” in those early documents), but also covered topics that included “automatic computers” and human-computer language interfaces (what we would today consider to be “programming languages”).

Fundamentally, the forerunners of this new field were concerned with translating dynamics of power and control into machine-readable formulations. McCarthy, Minsky, Herbert Simon (political scientist, economist, computer scientist, and eventual Nobel laureate), and Frank Rosenblatt (one of the originators of the “neural network” metaphor) were concerned with developing tools that could be used for the guidance of administrative — and ultimately— military systems. In an environment where the battle for American supremacy in the Cold War was being fought on all fronts — military, technological, engineering, and ideological — these men sought to gain favor and funding in the eyes of a defense apparatus trying to edge out the Soviets. They relied on huge claims with little to no empirical support, bad citation practices, and moving goalposts to justify their projects, which found purchase in Cold War America. These are the same set of practices that we see from today’s AI boosters, although they are now primarily chasing market valuations, in addition to government defense contracts.

The first move in the original AI hype playbook was foregrounding the fight with the Soviets. The second was to argue that computers were likely to match human capabilities by arguing that humans weren’t really all that complex. In 1956, Minsky claimed in an influential paper that “[h]uman beings are instances of certain kinds of very complicated machines.” If that were indeed the case, we could use more controllable electronic circuits in place of people in military and industrial contexts.

In the late 1960s, Joseph Weizenbaum, a German émigré, professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and contemporary of Minsky, was alarmed by how quickly people attributed agency to automated systems. Weizenbaum developed a chatbot called ELIZA, named for the working-class character in George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion who learns to mimic upperclass speech. ELIZA was designed to carry on a conversation in the style of a Rogerian psychotherapist; that is, the program primarily repeated what its users said, reframing their thoughts into questions. Weizenbaum used this form for ELIZA, not because he thought it would be useful as a therapist, but rather because it was a convenient setup for the chatbot: this kind of psychotherapy is one of the few conversational situations where it wouldn’t matter if the machine didn’t have access to other data about the world.

Despite its grave limitations, computer scientists used ELIZA to celebrate how thoroughly computers could replace human labor and heralded the entry into the artificial intelligence age. A shocked Weizenbaum spent the rest of his life as a critic of AI, noting that humans were not meat machines, while Minsky went on to found MIT’s AI laboratory and rake in funding from the Pentagon unhindered.

Cover of The AI Con: How to Fight Big Tech’s Hype and Create the Future We Want

Harper

The murky, unethical funding networks — through unfettered weapons manufacturing then, and with the addition of ballooning speculative venture capital investments now — around AI continue to this day. So does the drawing of false equivalences between the human brain and the calculating capabilities of machines. Claiming such false equivalences inspires awe, which, it turns out, can be used to reel in boatloads of money from investors whipped into a FOMO frenzy.

When we say boatloads, think megayachts: in January 2023, Microsoft announced that it intended to invest $10 billion in OpenAI. This is after Mustafa Suleyman (former CEO of DeepMind, made CEO of Microsoft AI in March 2024) and LinkedIn cofounder Reid Hoffman received a cool $1.3 billion from Microsoft and chipmaker Nvidia in a funding round to their young startup, Inflection.AI. OpenAI alums cofounded Anthropic, a company solely focused on creating generative AI tools, and received $580 million in an investment round led by crypto-scammer Sam Bankman-Fried. These startups, and a slew of others, have been chasing a gold mine of investment from venture capitalists and Big Tech companies, frequently without any clear path to robust monetization. By the second quarter of 2024, venture capital was dedicating $27.1 billion, or nearly half of their quarterly investments, to AI and machine learning companies.

The incentives to ride the AI hype train are clear and widespread — dress something up as AI and investments flow. But both the technologies and the hype around them are causing harm in the here and now.

Of Hype and Harm

There are applications of machine learning that are well scoped, well tested, and involve appropriate training data such that they deserve their place among the tools we use on a regular basis. These include such everyday things as spell-checkers (no longer simple dictionary look-ups, but able to flag real words used incorrectly) and other more specialized technologies like image processing used by radiologists to determine which parts of a scan or X-ray require the most scrutiny. But in the cacophony of marketing and startup pitches, these sensible use cases are swamped by promises of machines that can effectively do magic, leading users to rely on them for information, decision-making, or cost savings — often to their detriment or to the detriment of others.

As investor interest pushes AI hype to new heights, tech boosters have been promoting AI “solutions” in nearly every domain of human activity. We’re told that AI can shore up threadbare spots in social services, providing medical care and therapy to those who aren’t fortunate enough to have good access to health care, education to those who don’t live in a wealthy school district, and legal services for people who can’t afford a licensed attorney. We’re told that AI will provide individualized versions of all of these things, flexibly meeting user needs. We’re told that AI will “democratize” creative activity by allowing anyone to become an artist. We’re told that AI is on the verge of doing science for us, finally providing us with answers to urgent problems from medical breakthroughs (discovering a cure for cancer!) to the climate crisis (discovering a solution for global warming!). And self-driving cars are perpetually just around the corner (watch out: that means they’re about to run into you). But as you may have surmised from our snarky tone, these solutions are, by and large, AI hype. There are myriad cases in which AI solutions have been posed but fall short of their stated goals.

In 2017, a Palestinian man was arrested by Israeli authorities over a Facebook post in which he posed next to a bulldozer with the caption (in Arabic) of “good morning.” Facebook’s machine translation software rendered that as “hurt them” in English and “attack them” in Hebrew — and the Israeli authorities just took that at face value, never checking with any Arabic speakers to see if it was correct. Machine translation has also become a weak stopgap in other critical situations, such as in handling asylum cases. Here, the problem to solve is one of communication, between people fleeing violence in their home countries and immigration officials. Machine translation systems, which can work well in cases like translating newspapers written in standard varieties of a handful of dominant languages, can fail drastically in translating asylum claims written or spoken in minority languages or dialects.

In August 2020, thousands of British students, unable to take their A-level exams due to the COVID-19 pandemic, received grades calculated based on an algorithm that took as input, among other things, the grades that other students at their schools received in previous years. After massive public outcry, in which hundreds of students gathered outside the prime minister’s residence at 10 Downing Street in London, chanting “Fuck the algorithm!” the grades were retracted and replaced with grades based on teachers’ assessment of student work. In May 2023, Jared Mumm, a professor at Texas A&M University, suspected his students of cheating by using ChatGPT to write their final essays — so he input the essays into ChatGPT and asked it whether it wrote them. After reading ChatGPT’s affirmative output, he assigned the whole class incomplete grades, and some seniors were (temporarily) denied their diplomas.

On our roads, promises of self-driving cars have led to death and destruction. A Tesla employee died after engaging the so-called “Full Self-Driving” mode in his Tesla Model 3, which ran the car off the road. (We know this partially because his passenger survived the crash.) A few months later, on Thanksgiving Day 2022, Tesla CEO Elon Musk announced the availability of Tesla’s “Full Self-Driving” mode. Hours later, it was involved in an eight-car pileup on the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge.

In 2023, lawyer Steven A. Schwartz, representing a plaintiff in a lawsuit against an airline, submitted a legal brief citing legal precedents that he found by querying ChatGPT. When the lawyers defending the airline said they couldn’t find some of the cases cited and the judge asked Schwartz to submit them, he submitted excerpts, rather than the traditional full opinions. Ultimately, Schwartz had to own up to having trusted the output of ChatGPT to be accurate, and he and his cocounsel were sanctioned and fined by the court.

In November 2022, Meta released Galactica, a large language model trained on scientific text, and promoted it as able to “summarize academic papers, solve math problems, generate Wiki articles, write scientific code, annotate molecules and proteins, and more.” The demo stayed up for all of three days, while the worldwide science community traded examples of how it output pure fabrications, including fake citations, and could easily be prompted into outputting toxic content relayed in academic-looking prose.

What all of these stories have in common is that someone oversold an automated system, people used it based on what they were told it could do, and then they or others got hurt. Not all stories of AI hype fit this mold, but for those that don’t, it’s largely the case that the harm is either diffuse or undocumented. Sometimes, people are able to resist AI hype, think through the possible harms, and choose a different path. And that brings us to our goal in writing this book: preventing the harm from AI hype. When people can spot AI hype, they make better decisions about how and when to use automation, and they are in a better position to advocate for policies that constrain the use of automation by others.

Copyright © 2025 by Emily M. Bender and Alex Hanna

The murky, unethical funding networks — through unfettered weapons manufacturing then, and with the addition of ballooning speculative venture capital investments now — around AI continue to this day. So does the drawing of false equivalences between the human brain and the calculating capabilities of machines. Claiming such false equivalences inspires awe, which, it turns out, can be used to reel in boatloads of money from investors whipped into a FOMO frenzy.

When we say boatloads, think megayachts: in January 2023, Microsoft announced that it intended to invest $10 billion in OpenAI. This is after Mustafa Suleyman (former CEO of DeepMind, made CEO of Microsoft AI in March 2024) and LinkedIn cofounder Reid Hoffman received a cool $1.3 billion from Microsoft and chipmaker Nvidia in a funding round to their young startup, Inflection.AI. OpenAI alums cofounded Anthropic, a company solely focused on creating generative AI tools, and received $580 million in an investment round led by crypto-scammer Sam Bankman-Fried. These startups, and a slew of others, have been chasing a gold mine of investment from venture capitalists and Big Tech companies, frequently without any clear path to robust monetization. By the second quarter of 2024, venture capital was dedicating $27.1 billion, or nearly half of their quarterly investments, to AI and machine learning companies.

The incentives to ride the AI hype train are clear and widespread — dress something up as AI and investments flow. But both the technologies and the hype around them are causing harm in the here and now.

Of Hype and Harm

There are applications of machine learning that are well scoped, well tested, and involve appropriate training data such that they deserve their place among the tools we use on a regular basis. These include such everyday things as spell-checkers (no longer simple dictionary look-ups, but able to flag real words used incorrectly) and other more specialized technologies like image processing used by radiologists to determine which parts of a scan or X-ray require the most scrutiny. But in the cacophony of marketing and startup pitches, these sensible use cases are swamped by promises of machines that can effectively do magic, leading users to rely on them for information, decision-making, or cost savings — often to their detriment or to the detriment of others.

As investor interest pushes AI hype to new heights, tech boosters have been promoting AI “solutions” in nearly every domain of human activity. We’re told that AI can shore up threadbare spots in social services, providing medical care and therapy to those who aren’t fortunate enough to have good access to health care, education to those who don’t live in a wealthy school district, and legal services for people who can’t afford a licensed attorney. We’re told that AI will provide individualized versions of all of these things, flexibly meeting user needs. We’re told that AI will “democratize” creative activity by allowing anyone to become an artist. We’re told that AI is on the verge of doing science for us, finally providing us with answers to urgent problems from medical breakthroughs (discovering a cure for cancer!) to the climate crisis (discovering a solution for global warming!). And self-driving cars are perpetually just around the corner (watch out: that means they’re about to run into you). But as you may have surmised from our snarky tone, these solutions are, by and large, AI hype. There are myriad cases in which AI solutions have been posed but fall short of their stated goals.

In 2017, a Palestinian man was arrested by Israeli authorities over a Facebook post in which he posed next to a bulldozer with the caption (in Arabic) of “good morning.” Facebook’s machine translation software rendered that as “hurt them” in English and “attack them” in Hebrew — and the Israeli authorities just took that at face value, never checking with any Arabic speakers to see if it was correct. Machine translation has also become a weak stopgap in other critical situations, such as in handling asylum cases. Here, the problem to solve is one of communication, between people fleeing violence in their home countries and immigration officials. Machine translation systems, which can work well in cases like translating newspapers written in standard varieties of a handful of dominant languages, can fail drastically in translating asylum claims written or spoken in minority languages or dialects.

In August 2020, thousands of British students, unable to take their A-level exams due to the COVID-19 pandemic, received grades calculated based on an algorithm that took as input, among other things, the grades that other students at their schools received in previous years. After massive public outcry, in which hundreds of students gathered outside the prime minister’s residence at 10 Downing Street in London, chanting “Fuck the algorithm!” the grades were retracted and replaced with grades based on teachers’ assessment of student work. In May 2023, Jared Mumm, a professor at Texas A&M University, suspected his students of cheating by using ChatGPT to write their final essays — so he input the essays into ChatGPT and asked it whether it wrote them. After reading ChatGPT’s affirmative output, he assigned the whole class incomplete grades, and some seniors were (temporarily) denied their diplomas.

On our roads, promises of self-driving cars have led to death and destruction. A Tesla employee died after engaging the so-called “Full Self-Driving” mode in his Tesla Model 3, which ran the car off the road. (We know this partially because his passenger survived the crash.) A few months later, on Thanksgiving Day 2022, Tesla CEO Elon Musk announced the availability of Tesla’s “Full Self-Driving” mode. Hours later, it was involved in an eight-car pileup on the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge.

In 2023, lawyer Steven A. Schwartz, representing a plaintiff in a lawsuit against an airline, submitted a legal brief citing legal precedents that he found by querying ChatGPT. When the lawyers defending the airline said they couldn’t find some of the cases cited and the judge asked Schwartz to submit them, he submitted excerpts, rather than the traditional full opinions. Ultimately, Schwartz had to own up to having trusted the output of ChatGPT to be accurate, and he and his cocounsel were sanctioned and fined by the court.

In November 2022, Meta released Galactica, a large language model trained on scientific text, and promoted it as able to “summarize academic papers, solve math problems, generate Wiki articles, write scientific code, annotate molecules and proteins, and more.” The demo stayed up for all of three days, while the worldwide science community traded examples of how it output pure fabrications, including fake citations, and could easily be prompted into outputting toxic content relayed in academic-looking prose.

What all of these stories have in common is that someone oversold an automated system, people used it based on what they were told it could do, and then they or others got hurt. Not all stories of AI hype fit this mold, but for those that don’t, it’s largely the case that the harm is either diffuse or undocumented. Sometimes, people are able to resist AI hype, think through the possible harms, and choose a different path. And that brings us to our goal in writing this book: preventing the harm from AI hype. When people can spot AI hype, they make better decisions about how and when to use automation, and they are in a better position to advocate for policies that constrain the use of automation by others.

Copyright © 2025 by Emily M. Bender and Alex Hanna

Emily M. Bender

Dr. Emily M. Bender is a professor of linguistics at the University of Washington, where she is also the faculty director of the Computational Linguistics Master of Science program and affiliate faculty in the School of Computer Science and Engineering and the Information School. In 2023, she was included in the inaugural TIME 100 list of the most influential people in AI. She is frequently consulted by policy makers, from municipal officials to the federal government to the United Nations, for insight into how to understand so-called AI technologies.

Alex Hanna

Dr. Alex Hanna is director of research at the Distributed AI Research Institute (DAIR) and a lecturer in the School of Information at the University of California Berkeley. She is an outspoken critic of the tech industry, a proponent of community-based uses of technology, and a highly sought-after speaker and expert who has been featured across the media, including articles in The Washington Post, Financial Times, The Atlantic, and TIME.

Amazon drivers strike in Bologna, Italy, on April 18, 2025. The picket sign calls for higher pay and lighter package loads for drivers.Giuseppe Picconetti

Amazon drivers strike in Bologna, Italy, on April 18, 2025. The picket sign calls for higher pay and lighter package loads for drivers.Giuseppe Picconetti