An extraordinary South African story

Almost twenty years old, I now had the opportunity to define my life according to my own precepts.

I had been groomed by Uncle Kenny to regard myself as different from other women of my age. He stressed that I was more articulate and intelligent, and would never be able to settle into the humdrum ways of ordinary township life.

Even when I was a child in KwaGuqa, my uncle would time his unexpected visits to coincide with my school holidays and, sweeping Ouma’s excuses aside, have my bags packed and drive off with me to his home in Springs. When I was driven back, his DKW would be full of packages of clothes and toys for me. Once, he even bought me a bicycle.

I never cried when my uncle left me back in KwaGuqa. I was always filled with awe and confidence, because he always came back for me. We would pay a surprise visit to my parents in Alexandra, who would be astounded by my appearance.

According to our Setlokwa custom, my father’s brothers were my fathers and their children were my brothers and my sisters. Uncle Kenny delighted in the exclamations of my parents as we made our surprise entrance.

READ: Felleng Yende | Redistribute resources in favour of women

Those were the best times of my childhood, and I never felt sad about waving goodbye to my parents as the case would be when they would leave KwaGuqa after a visit.

Uncle Kenny healed the deep feelings of orphanhood that used to wrack my body into an upheaval of shivers and hiccups long after the tears had gone. I loved him almost as much as I loved my brother, and my life afterwards, as a growing adult, would always be lacking without either of them. No one ever measured up to their high standing in my universe.

So, as I entered the stage of courtship, my yardstick shifted and slid to approximate the wit, the humour and the swaggering intelligence of those two: there was always something wanting in my suitors.

Many journalists came to the New Age offices to verify and follow up on stories, not least to get information about arrested leaders and other activists – the editor Fred Carneson, for instance.

Like many others who visited the office, Carneson had been a Treason Trialist, arrested over sixty times for his political activities. He was on trial for refusing to reveal the sources of a story in the paper.

Young journalists at Drum magazine, Golden City Post and the like often came to our offices to meet with Joe Gqabi or Ruth First. Govan Mbeki, who was on the New Age editorial board and was based in the Eastern Cape, was a frequent visitor.

As a new employee, I was not familiar with many of the activists who closed the door behind themselves when they entered Ruth and Kathy Kathrada’s office. They were well known to Joyce Mohamed and to Esther Mtshali, my colleagues who were in the inner circles of the movement.

I met Nat Nakasa at the New Age offices. Like many journalists, he had come to get information about a story.

The most frequent visitors were lawyers and trade union members. I recognised people such as Walter Sisulu, Nelson Mandela, Titus Nkobi and Duma Nokwe from my childhood days when they addressed ANC meetings at the square in Alexandra near 12th Avenue, and from photographs in the newspapers.

The atmosphere at the office was very relaxed. I do not remember being vetted or questioned about my background, and I never witnessed a quarrel among the comrades or sensed the existence of a cult surrounding any of the leaders.

Nor was there any open demonstration of hierarchy. Despite the deepening repression and the growing number of arrests, there was a cheerful air that ruled the interactions that were focused on the liberation struggle.

Soon I was riding on the back of Nat’s scooter and accompanying him to shebeens in Johannesburg and Soweto. Ours was more of a companionship than a love affair.

I remember that he came to pick me up for a date once, all agog because he had met the daughter of one of the wealthiest men in South Africa and she had agreed to go on a date with him.

It did not affect me; in the short time I had known him, I had learnt that he was a sucker for short-lived infatuations that soon petered out. He took me to my first “mixed party” at the home of Nadine Gordimer.

Nat was greatly influenced by his homeboy Lewis Nkosi, for whom he had great regard and admiration. Nkosi had introduced him to the Johannesburg scene and it was not long before he developed his own professional and social reputation. For one, he managed to win my father over and became a family friend rather than a suitor.

Both my parents spoke freely to him about their work in the Natalspruit Municipality. He had liaisons with other women and never made a secret of it, but he liked my company and we became very close friends and intellectual mates who shared opinions about books and writers.

It is during this time that I first met Yolisa Bokwe, with whom I have shared a friendship for over sixty years. Originally from Middeldrift in the Eastern Cape, she came to Johannesburg from Birmingham in England, where she had studied classical music. She taught the piano at Dorkay House.

Nat Nakasa took one look at this sophisticated, petite beauty and fell in love. I met her in Robinson Deep through Joyce Piliso, who was a neighbour of friends of my parents, the Denalanes.

We still roll about laughing when remembering the story of my arrest. It was a Sunday morning and I was at Yolisa’s cottage in a back yard in Parktown. There was a knock at the door and when Yoli opened it, a big white policeman shadowed the way and demanded to know what we were doing in a white area. He took our passes and we were under arrest.

As we waited for the police van to arrive, Yoli asked the policeman if she could go to the lavatory. He agreed, rather too readily. It was the custom of the police, then, to drive around all day collecting suspects and only to return to the police station when the van was full.

This was to be our fate too, but there was no Yolisa to be my partner in “crime” that day: she had climbed through the toilet window and escaped.

It was only when the van arrived with two more constables that it dawned on me that she had gone. I felt abandoned and betrayed as I bounced up and down in the empty van, which stopped periodically to pick up more reluctant passengers. Eventually, at dusk, after my charges were confirmed, I was taken to the women’s prison, where the Constitutional Court is now located.

I prepared myself for my first night in prison – ablution bucket, clanging doors and all. The cell reeked of dirt, dust, sweat and urine, and, for the first time, it dawned on me that I really was under arrest.

As I was coming to terms with my plight, there was a noise at the door, which was being unlocked, as my name was shouted out loudly.

I came out following the policeman. There, at the big counter, was a friend waiting. It was Andrew Lukhele, an advocate who was also a good friend and an Alexandra resident. He had managed to negotiate a trespass fine and I was free.

Outside waiting in his car was dear Yolisa.

I was impressed that her escape was not only to save herself, but to seek and find help to get me out of jail. Our friendship continues to thrive and I still rely on her for cool-headed, practical solutions.

But at this time, marriage was furthest from my mind. I was still looking forward to entering university and, with Uncle Kenny’s encouragement, had applied to what was then Pius XII University, at Roma Mission in Lesotho. When I had refused to go to the Bantustan Turfloop University, 1961 became a gap year for me.

The sexual terrorism I had experienced in Alexandra as a very young teenager, the train journey to Inanda Seminary with testosterone-charged young men on the rampage in the train corridors, the lustful conduct of close male friends as soon as you were alone with them, the bold remarks about one’s physical attributes, and more, did not make for a keen interest in a relationship.

There was something that turned men beastly about sex and it did not assist in one’s own self-regard. Additionally, coming from Inanda, the idea of men in charge, of men casually treating women as children they could rebuke – even punish and control – had become anathema, even as it was a common occurrence in society.

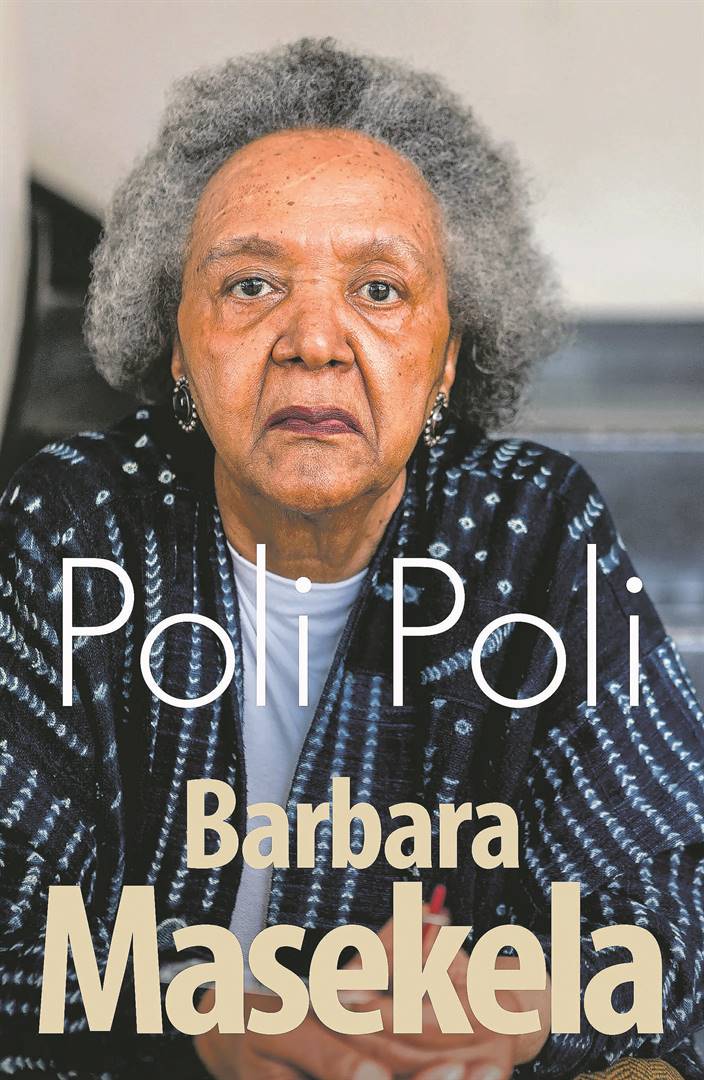

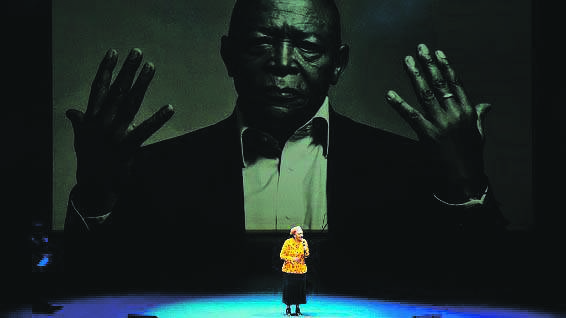

Masekela is SA’s former ambassador to the US. Her autobiography, Poli Poli, is published by Jonathan Ball