Supported by

Dianna Wray

Sun 5 Sep 2021

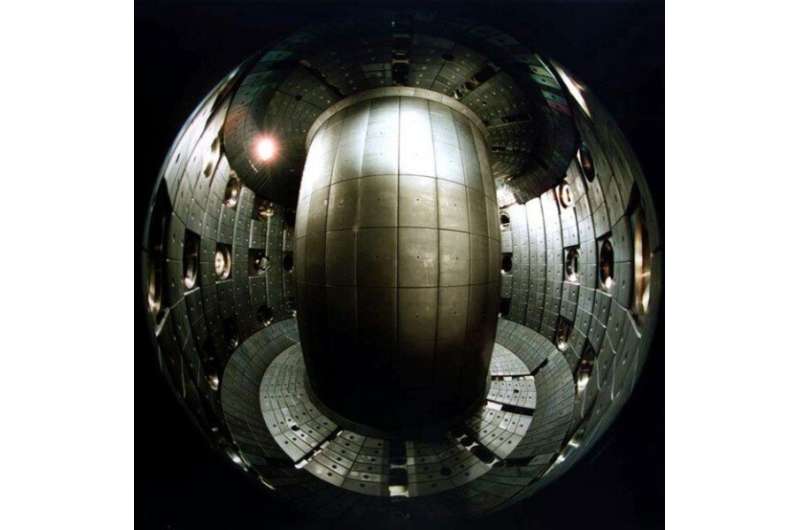

Everything seemed normal as SpaceX’s Starship juddered into the sky over south Texas last March, tangerine flames and white smoke pluming behind it. But roughly six minutes into the test flight, the spacecraft thudded back to Earth.

SpaceX, the company founded by Elon Musk in 2002, has a “test, fly, fail, fix, repeat” method for its commercial space program. That approach is part of why Musk wanted to put the launch site on a tract of land just off the Gulf of Mexico, close to the Texas border with Mexico. “We’ve got a lot of land with nobody around, so if it blows up, it’s cool,” Musk reportedly said at a press conference in 2018.

How the billionaire space race could be one giant leap for pollution

But David Newstead, director of the nonprofit Coastal Bend Bays and Estuaries, felt sick as he saw the fireball explode on the launchpad. SpaceX’s site is surrounded by state and federally protected lands. The explosion littered parts of the delicate ecosystem of the Boca Chica tract of the Lower Rio Grande Valley national wildlife refuge – comprising tidal flats, beaches, grasslands and coastal dunes that host a huge range of wildlife – with rocket debris.

“I knew from the other explosions that the rocket would be scattered all over the refuge,” Newstead said. Cleanup took three months, he added.

The private space race is already causing concern about the potential climate impacts of the fuel needed to propel the rockets. But environmentalists on the ground in south Texas say SpaceX’s testing site is having more immediate impacts.

The refuge is made up of parcels the US Fish and Wildlife Service has been buying or leasing since 1979 when the federal agency came up with its plan to preserve as much of the land tucked against the Gulf Coast and the mouth of the Rio Grande River as possible, creating a patchwork of federally managed refuge land. As part of that, the agency has been managing Boca Chica state park, a 1,000-acre (404 hectare) site, since 2007.

Boca Chica is a key piece of the Laguna Madre hypersaline lagoon system and home to a plethora of vulnerable species. The Kemp’s Ridley sea turtles nest on the shore of Boca Chica Beach each spring, while shorebirds such as plovers peck at the tidal flats to find food. The refuge is also home to endangered ocelots, the wild cats that once roamed across the south-west.

“It’s one of the most unique places on Earth,” said Jim Chapman, a local environmentalist with Save Rio Grande Valley.

Many Texas officials consider SpaceX’s presence a coup for the state. They had been interested in wooing Musk since he first began talking about building a private space port in 2011. State legislators passed a bill in 2013, which gave SpaceX the right to close Boca Chica beach during testing and launches. They also permitted limited road closures to Texas’ Highway 4, the only road to the SpaceX site – and to the Boca Chica section of the refuge.

In 2014, the Federal Aviation Administration issued its environmental impact statement, finding that SpaceX’s proposal for the region “would have no significant impact on the environment”. It didn’t seem like a big deal at the time, Newstead said, most people assumed that the anglers and beachgoers, the US Fish and Wildlife refuge managers who monitored the sea turtles and the conservationists studying the region’s more than 200 bird species would be able to coexist with SpaceX.

When Musk formally announced Boca Chica had been selected, most people focused on the opportunity. “We were seen as a border town, with all the negative national rhetoric that goes along with that,” said Josh Mejia, executive director of the Brownsville Community Investment Corporation. “But SpaceX choosing to build here, that gave us tremendous validation. Other businesses finally started looking at us and seeing potential.”

SpaceX’s activity on the ground ramped up as rocket testing began in 2019. Dirt mounds were quickly replaced by fuel storage tanks, construction equipment, a sea of Airstream trailers, and the latest rocket gleaming on the launchpad. SpaceX employees and contractors were constantly driving up and down Texas State Highway 4 and using roadsides – technically state land managed by the US Fish and Wildlife Service – for parking.

In April, SpaceX applied to expand its current site by filling in 17 acres of wetlands, which the EPA suggested could have “substantial and unacceptable adverse impacts on aquatic resources of national importance”.

Local environmentalists have grown increasingly concerned that SpaceX is dominating the road and the refuge land around it, closing roads and beaches for longer than their 300 permitted hours. In 2019, US Fish and Wildlife sent a letter to the FAA asking that SpaceX’s road closures and testing be halted until “noncompliance issues are resolved”. In June, the agency again wrote to the FAA about SpaceX reporting “unauthorized encroachments and trespass on the refuge”, according to 60 Minutes, including parking on refuge land and installing a drainage ditch.

In 2021, Save Rio Grande Valley wrote to the Cameron county district attorney claiming that SpaceX had cut off access to the beach and the refuge for more than 1,000 hours. In response to the district attorney’s inquiries, SpaceX denied the company road closures have exceeded the permitted 300 hours stating that the local environmentalists’ claims were “not accurate”.

“It’s really been shocking to witness the way the federal government has allowed this to happen,” said Bryan Bird, of the national environmental nonprofit Defenders of Wildlife. “Elon Musk is building a space complex in one of the most environmentally diverse, and inappropriate, places in the world.”

Advertisement

Launch site ditches, both on SpaceX land and public property, have dumped runoff water directly into the tidal flats, said Newstead, where he and his fieldworkers track nesting sites for snowy plovers, a wading bird that is close to landing on the federal threatened species list.

It would take a government agency to conduct the intensive rounds of ecological monitoring and study needed to understand how local wildlife is being affected by SpaceX’s presence, Newstead said, but he’s already seen a change in the snowy plovers.

There used to be about a dozen nests dotting the tidal flats on the edge of Boca Chica where the refuge abuts SpaceX’s property each spring, but last year the organization found just two pairs of the snowy plovers nesting, he said. This year they only spotted one. Newstead has also scaled back the nonprofit’s annual migratory bird census and multiple other programs, because, he says, they can’t access the refuge often enough to properly conduct the survey.

“These are complex systems, some of the only ones of their kind left in the world,” Newstead said. “I never thought there would be no impact whatsoever to SpaceX being here, but I did think government agencies would do more to ensure that things like this wouldn’t happen. I’m afraid of what we’ll find when we go out looking for their nests next spring.”

Jim Blackburn, a professor of environmental law at Rice University, said complaints about a lack of enforcement of environmental regulations are common. “A lot of people think that because we have these laws, the environment is protected, but that’s not how it works. People working on the ground for these agencies are often well meaning, but if the political will is there to allow a project like SpaceX to go through, that’s what happens.”

Advertisement

Neither SpaceX nor the US Fish and Wildlife Service responded to the Guardian’s requests for comment. The FAA told the Guardian that closures are implemented and enforced locally. It added that the 2014 environmental impact statement and the subsequent alterations remain valid, that the agency is still working on its environmental assessment of SpaceX’s revised plans for its launch testing site, and has no publication date at this time.

SpaceX has plans to launch the biggest rocket in the world, the Super Heavy booster and Starship, from Texas. SpaceX representatives have said they are eager to begin testing the new system, a process that many environmental campaigners in the community believe will ultimately see more rocket shrapnel lacerating refuge lands. The FAA is currently conducting an environmental assessment.

In 40 years of working to protect the Lower Rio Grande Valley national wildlife refuge, Chapman said he has never been more concerned. “People love space, they love the hype and glamour of rockets around here, but everything has a price,” Chapman said. “There’s always someone coming along who wants to develop the land out here. It used to be that we could rely on the government to step in, but now I’m not so sure about that.”