Is it too late to halt deep-sea mining? Meet the activists trying to save the seabed

If mining companies are given the go-ahead to exploit the ocean depths, the environmental cost will be devastating. As the clock ticks down to a crucial deadline in July, Michael Segalov reports

Michael SegalovTHE OBSERVER

Sun 21 May 2023

For almost 30 years, much of what went on at the secretive-sounding International Seabed Authority (ISA) in Jamaica was unreported and scarcely noticed. Whatever was said by delegations from its 168 member countries in its cavernous assembly hall – all mustard chairs, in-ear live interpreters, UN-style country place cards and views out to the Caribbean Sea – was seemingly of interest to only a smattering of environmental NGO types and a handful of representatives from vague-sounding international businesses.

Over the past 18 months, however, more attention has been turning towards the negotiations taking place inside the ISA’s brutalist HQ on the Kingston coast, where the authority has, since 1994, been tasked with deciding if and how mining the deep sea for metals and minerals – once the preserve of science fiction, now edging ever closer to reality – might start to take place n in international waters on the ocean floor.

There have been allegations of secrecy and interference against its governing body and of legal loopholes being exploited. After discussions chugged along quietly for decades, a growing community of campaigners, scientists and now governments are raising an urgent alarm about what’s happening within these walls. They argue that unless immediate action is taken, it might be too late to halt the devastating environmental and ecological impact of mining the global high seas. Their warning is simple: humanity’s insatiable appetite to plunder the planet for profit might mean some of the Earth’s most untouched corners are exploited before we even understand what it is we risk losing. As Louisa Casson, who is leading Greenpeace’s global campaign to stop deep-sea mining, puts it: “It’s a threat, continental in scale, that until recently nobody was even talking about.”

These groups have support from all sorts of places. Global brands including Samsung, Google, Volvo, Philips and BMW have joined the chorus. Countries including Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, New Zealand and Spain have expressed opposition, and an all-out ban has been demanded by France’s President Macron.

Regardless, due to a quirk in an ageing international treaty, deep-sea mining might happen in a matter of months after the pulling of a legal lever by a Canadian-owned company and the government of Nauru. Some believe the ISA’s members have been delivered a legitimate ultimatum: either agree the regulations for mining within two years or allow it to go ahead regardless. Others argue this is a worrying misinterpretation of the body’s ruling text. Either way, the clock runs out this July. There’s every reason to be concerned. That said, on my first morning at the ISA’s 28th session on a bright Tuesday in March there’s little sign of an impending emergency. The debates are anything but fevered. Suited diplomats potter quietly; a merch rail sells ISA-branded T-shirts outside the main assembly room.

Inside, discussions are being held on agenda item 10, Fourth Meeting of the Informal Working Group on the Protection and Preservation of the Marine Environment: Continued Negotiations on the Facilitator’s Further Revised text. It’s slow and tedious. One by one, state delegations lay out their positions. Russia, the UK and Korea discuss the use of the word “synergistic”. Australia wants to tweak a sentence. Norway asks how paragraph five relates to paragraph three. It’s only at the end of each scheduled topic that discussions take on a more pressing tone. In these gaps, those sitting in the galleries above – environmental groups, scientists, conservationists and indigenous activists – make interventions in an effort to shift the focus away from the granular detail and back to the fundamental question of whether deep-sea mining should be allowed to start.

Dr Diva Amon is a Trinidad and Tobago-based deep-sea biologist who has attended these meetings since 2017. “When I first started coming,” she says, “it was very different. We’ve gone from broad discussions to regulations being drawn up, and now negotiated line-by-line. Honestly? It’s like watching paint dry.”

‘It’s a threat, continental in scale, that nobody was even talking about’: Uncle Sol Kaho’ohalahala flanked by Jonathan Mesulam and activist Alanna Smith. Photograph: Yannick Ried

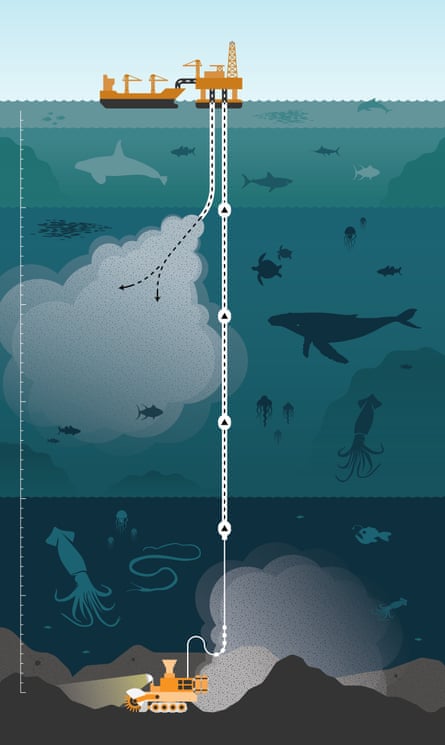

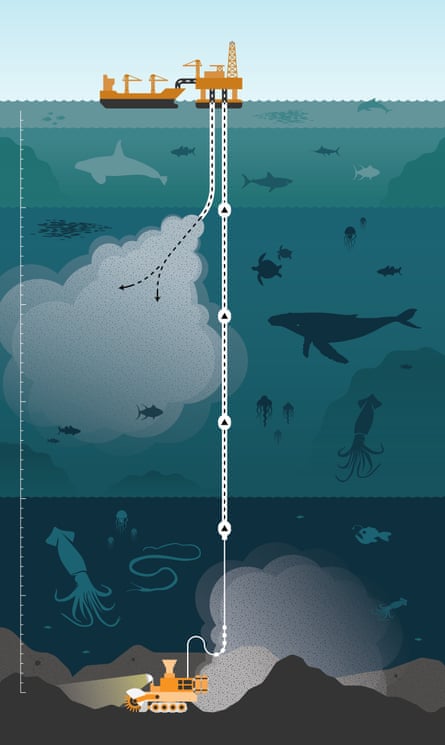

Still, she lays out the basics. Since the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea came into force in 1994, nation states have had the right to exploit and explore natural resources, such as wind and wave energy in waters up to 200 nautical miles off their respective coastlines. This international treaty saw countries establish the ISA. What happens on the sea bed beyond these ocean borders was left for ISA members to decide. “That’s 40% of the entire planet’s surface it’s responsible for,” explains Amon. “Because of the vast depths of these oceans, that equates to 90% of the habitable space where animals can live.”

Deep-sea mining exploration and research has been ongoing since the 1960s, but nothing on an industrial scale has yet begun. Much of the technology it would require remains in development, or it’s privately owned and commercially sensitive, and out of the public domain. Regulations for mining are yet to be agreed upon. There’s a vagueness, therefore, to some of the specifics of how mining might occur for various metals and minerals: nickel, cobalt, manganese and copper, gold, silver and platinum.

Mining’s major proponents, notably a small collection of European and North American companies, say these materials are needed for renewable technology, in particular car batteries. It’s not just scientists and environmentalists who take issue with this suggestion (“It’s like smoking to ease stress,” says Amon, “a short-term fix that does far more long-term harm”), but car manufacturers, too. BMW, Volvo, Volkswagen and Renault have all called for a moratorium on deep-sea mining, saying they won’t use these materials in their products. Regardless, miners hope to drill into hydrothermal vents (those iconic deep-sea chimneys), and also extract metals from mountains protruding from the seabed. Most commonly explored, however, and likely to be the first mining undertaken, are what’s known as polymetallic nodules: lumps of metals and minerals mixed with all sorts of sediment which sit on the ocean floor.

This mining will see hordes of large mining machines moving along the seafloor like bulldozing combine harvesters, scooping up nodules and whatever else is in their path. “Everything around them will be disturbed,” says Amon. “The top 10cm for certain, home to the majority of life on the seafloor. That means huge amounts of habitat and animals will be lost.” Out the back, water, sediment and shredded wildlife will be pumped out, wreaking havoc. Everything else collected will be pumped through a network of pipes up to a ship on the surface. “Here the nodules will be separated from other materials like water, sediment and likely crumbled pieces of metal that will be spewed out into the ocean as waste.”

For scientists like Amon, it’s of huge concern. “If the technology being discussed is used, we know all this will be affected. What’s unknown is the extent.”

Last year she co-authored a paper which found that across all the areas where mining exploration had started, only 1.1% of the science required to ascertain its impact had been done. We simply do not know enough. The deep sea, she accepts, might well feel distant. “But not only is it full of life,” she makes clear, “a biodiversity reservoir, with two thirds of the species that live there still undiscovered, it’s also essential to the planet being habitable.” There’s the ocean’s climate regulation: carbon is locked away beneath the seabed and the ocean absorbs heat (scientists have determined that the ocean absorbs more than 90% of excess heat attributed to greenhouse gas emissions). Billions rely on fish and seafood as a primary source of protein. “And deep-sea life, having survived in extreme conditions, has evolved in ways that are already proving hugely helpful for humanity,” Amon continues. “We’re only just scratching the surface, but we’re finding compounds down there useful for everything from new medicine to household work. There’s so much to tap into that is still unknown.”

With the clock ticking towards the July deadline, the cacophony of opposition to deep-sea mining gets louder. Over the days I’m present at the ISA, two more countries add their names to the list of nations calling for a pause – Vanuatu and the Dominican Republic. But it’s not only a scientific case for a mining moratorium that is being made. At this meeting, for the first time, a delegation of Pacific Island activists are in attendance, each bringing with them the perspective of oceanic communities who, they say, for too long have been left unheard in this debate.

Uncle Sol Kaho’ohalahala is one of them. A seventh-generation resident of Lanai, an island of Hawaii, his relationship with the ocean is profound. Through the 1950s and 60s, he was part of an indigenous group that fought the US army using the Hawaiian island of Kahoolawe as a bombing range, and he’s spent 40 years traversing the Pacific as crew on a traditional canoe. For indigenous Hawaiians, a relationship with the ocean can be traced back to humankind’s creation. “The Kumulipo is our genealogy,” he says, “our chant of creation. It tells us the first creature was the coral polyp. And from that, all creatures follow.” To Uncle Sol and his community, therefore, deep-sea mining isn’t only a scientific and environmental issue, it would be an act of cultural vandalism, too. “Our responsibility as native Hawaiians is to honour our elders and ancestors,” he says. “And our oldest ancestor is in the ocean. At some point, it was decided the ocean belongs to nobody. I challenge that. It belongs to us – people here need to know this is my country they are about to do irreparable damage to.”

Digging deep: from the top 200m sunlight zone, through twilight and midnight zones,

to the abyss, at 600m.

Illustration: Carlos Coelho @ debut art

Another indigenous activist, Jonathan Mesulam, shares stories of fighting deep-sea mining for a decade in his home country of Papua New Guinea. “It’s common knowledge that any industry on this scale will cause damage to the environment,” he explains one afternoon over lunch. “We’ve seen it on our land, with logging and mining; we had no doubt the same devastation would be caused by mining at sea.” A teacher by profession, he started to campaign on behalf of his coastal community. “The sea is our home. We’ve survived for generations from marine resources. What’ll happen to us if this goes ahead? Fisheries support the local and national economy. Our traditional practices rely on our waters. This would disturb it all.”

Mesulam successfully fought off mining in Papua New Guinea. Many of those same executives are now involved in the Canadian company working with Nauru.

Despite the best efforts of those desperately trying to change the tide of the debate, the ISA meeting mostly remains on course. At evening and lunchtime events, attempts are made by campaigners to lobby delegates. But the ISA’s secretariat, its administrative body, shows little interest in entertaining the question of pressing pause. Frustration has already begun to bubble up. At the start of this meeting, a German minister wrote to the ISA’s secretary general, British lawyer Michael Lodge, implying he had abandoned neutrality and was interfering with decisions being made. Lodge responded, rejecting the allegations.

When I meet Greenpeace’s Louisa Casson at the end of my week at the ISA, she argues this is symptomatic of a deeper problem. “The ISA has never turned down a licence to explore for mining,” she says, “and it benefits from every application – around $500,000 for each one, and they’re paid regular fees by the contractors. People are questioning how they can be a regulator when they have such a financial interest.” Lodge has also sometimes appeared to downplay environmental concerns – he once told an interviewer: “Turtles with straws up their noses and dolphins are very, very easy to get public sympathy.” He even appeared in a promotional video for a mining company. In a film made by DeepGreen Metals, Lodge appeared on a ship alongside its executives who were promoting deep-sea mining. In a statement, an ISA spokesperson reiterated its commitment to “protecting the environment as a prerequisite for any mining activity”, and said that the footage of Lodge, who was on an official visit, was used without the organisation’s consent.

“The law of the sea says you can only start deep-sea mining if you can ensure there won’t be harm to the marine environment,” explains Casson, “and that it will benefit humankind. Right now, neither of those conditions can be met.” Not a single scientist I speak to makes the case that it’s sensible and safe to start mining now. “And how on earth could this be considered for the good of humankind,” Casson asks, “when the industry is so concentrated in privately owned companies?”

It’s why, she argues, this controversial two-year rule has been tugged. “It stinks of desperation. The only people actively making the case for mining starting now are the companies themselves. For many, it’s their entire business model. But as deep-sea mining gains a public profile, more and more governments turn against it. Earlier this year, we signed a global oceans treaty: it makes no sense to now undermine this with a new destructive industry.”

There are certainly signs that it might be possible to stop deep-sea mining before it even starts. Protecting a part of the planet so untouched and unspoiled? It’s the rarest of opportunities. There are positive signs. Weapons manufacturer Lockheed Martin, the industry’s longest-running and biggest player, recently sold off its seabed mining interests. Just last week, major Danish shipping giant Maersk, dropped its investment in a deep-sea mining company, too.

When the ISA was established, little was known about what lived deep in our oceans, or how important these environments were. We now know so much more. No conclusion was come to at the end of this most recent ISA meeting. The can was kicked down the road. Delegations will return this July, with no more room for delay. As a complicated legal battle unfolds, politicians will be faced with a simple question. “And that,” says Casson, “is should the world be bullied into destroying our oceans because a few businesses want to get rich quick based on an outdated rule? Or should global governments wrestle back control? The answer is really obvious.”