India-Canada Rift: Breaking Down the Socio-Economic Ties in Numbers

Image Courtesy: PTI

The diplomatic tensions between India and Canada existed for quite a long time. It became apparent as early as Indian independence when Canada supported a plebiscite in Kashmir in 1948. The top leadership of both nations have been at odds over the issue of Khalistan extremism in Canada. It hit a new low on September 19 when the prime Minister of Canada claimed that there was evidence to suggest a potential link between the murder of a Canadian Citizen- who happens to be wanted in India- and the Indian Government.

While tensions have existed between the two countries on one or two fronts, their relationship has generally been favourable for each other, and the connection happens to be deep and old, as Canada is one of the top preferences for Indians to immigrate, especially from the state of Punjab. Canada is home to more Sikhs than India. Here, we decode the socio-economic connection in numbers.

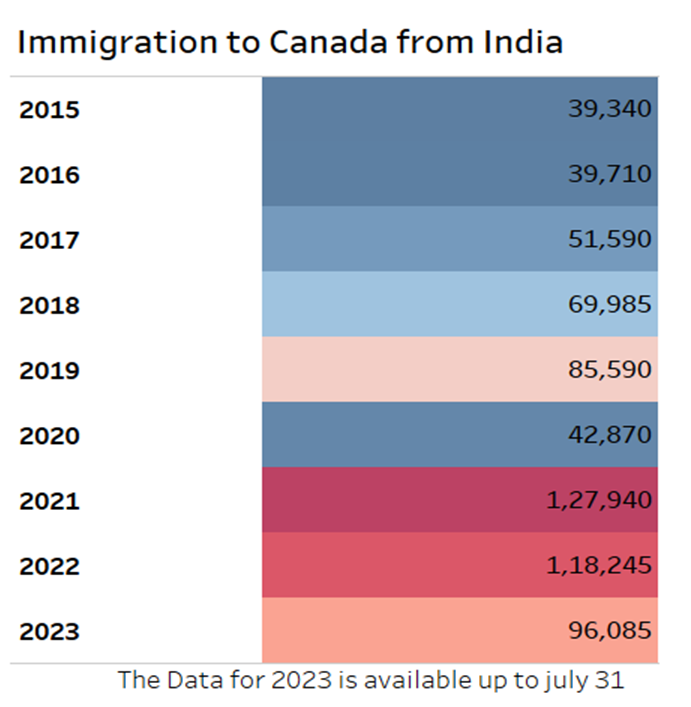

Indian Immigration to Canada Tripled in Just Seven Years

There are certain places in Canada, like Brampton, called Mini Punjab. Indians, especially the Sikh community, are a considerable share of the population in Canada. Immigration to Canada from India has witnessed a significant increase over the years. In the mere course of seven years, from 2015 to 2022, the number of people immigrating to Canada from India has increased by more than three times. In 2015, the number stood at 39,340, which increased to 1,18,245 in 2022.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused the number to fall to 42,870 in 2020 from 85,590 in 2019.

The number of Indians who became permanent residents in Canada rose from 39,000 in 2015 to 1,18,000 in 2022, a staggering increase of 202%, according to data available from Immigration, refugee & citizenship Canada.

In 2021, a whopping 1,27,940 Indians became permanent residents of Canada, increasing from 42,870 in 2020, a COVID-19 hit year. Arguably, this increase wasn’t just because of the ease of travel after COVID-19 but also due to restrictive immigration policies in the United States, particularly in the Trump administration.

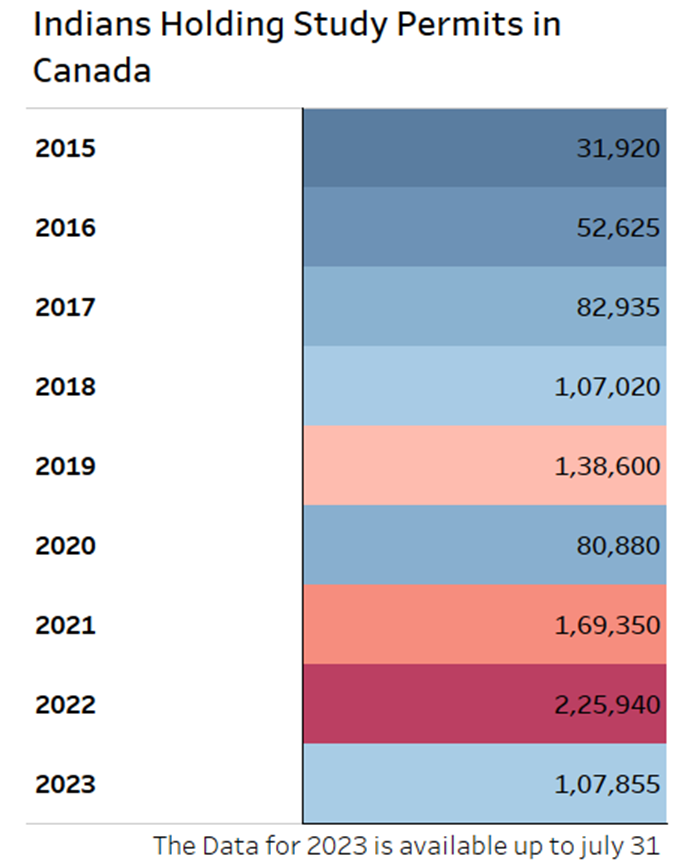

Indians With Study Permits In Canada Increased by 625%

The number of Indians living temporarily in Canada with study permits was just 31,920 in 2015, as per the data maintained by IRCC. This number increased to 2,25,940 in 2022, making it an increase of 625%. The number fell during the COVID-19 year. However, there was again a staggering increase of 33% from 1,69,350 in 2021 to 2,25,940 in 2022. 1,07,885 Indians have already received study permits till July 2023 to live temporarily in Canada.

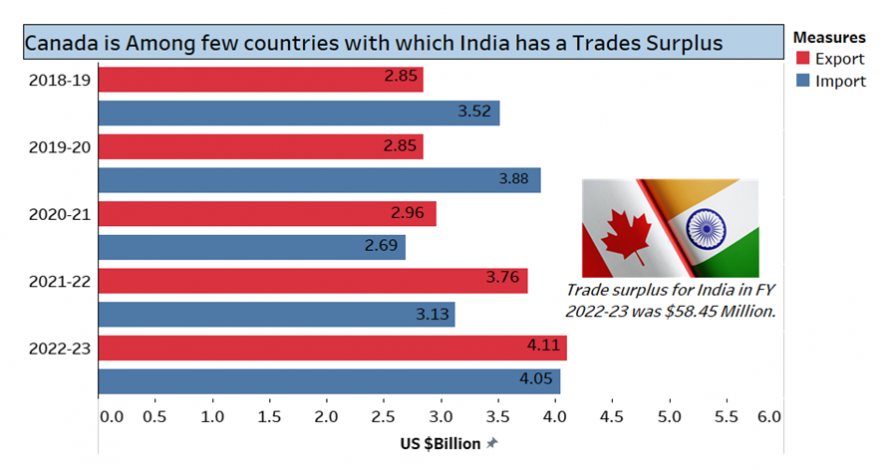

The Bilateral Trade is in Favour of India

There has been a net increase of 15% in Canadian imports from 3.52 billion dollars in the financial year 2018-19 to 4.05 billion dollars in 2022-23. Meanwhile, exports from India to Canada increased by 44% in the given period, from 2.85 billion dollars in 2018-19 to 4.11 billion dollars in the financial year 2022-23. Notably, Canada is not a big trading partner of India. India’s bilateral trade with Canada stood at 8.16 billion dollars during the FY 2022-23, which is 0.7% of the total.

Canada is among the few countries with which India trades in surplus. The trade balance favoured India with a 58.45 million dollar Trade balance in FY 2022-23. Regrettably, it has seen a sharp contraction in previous financial year. The trade balance in the financial year 2020-21 was 274.33 MDs- favouring India- increased to 631.21 million dollars, which sharply dropped in FY 2022-23, leaving a trade surplus of 58.45 million dollars.

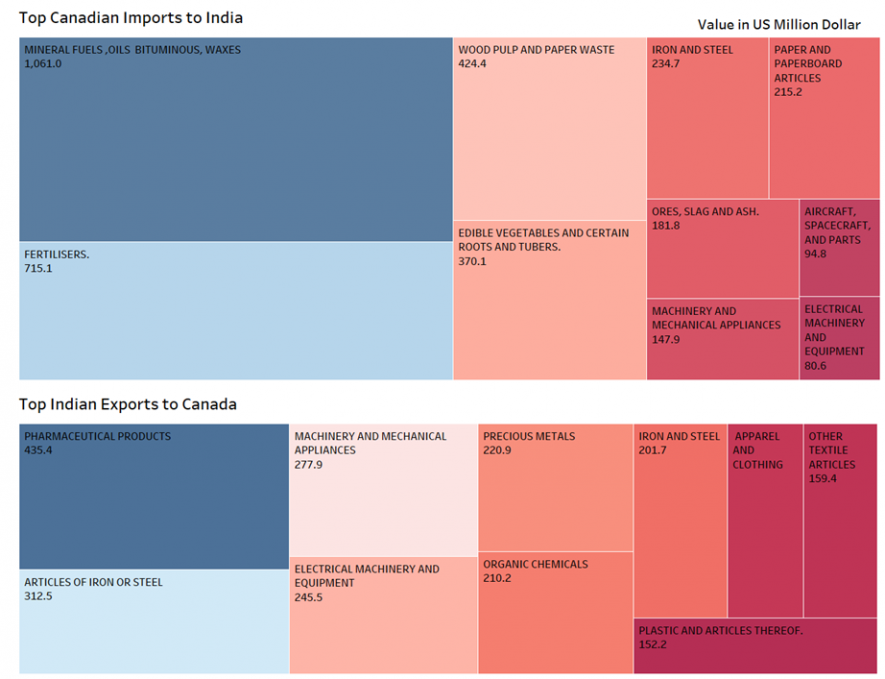

Minerals, fertilisers, paper products, and machines are the few top imports from Canada. In the financial year 2022-23, India imported commodities like mineral fuels, mineral oils, bituminous, and mineral waxes worth 1061 million dollars, which accounts for a 26% share of total imports in the given year.

Pharmaceutical products, articles of Iron or Steel, machines, precious metals, and organic chemicals are top export commodities from India to Canada. In 2022-23, India exported commodities of 4109 million dollars to Canada. The top ten export items accounted for 57% of the total worth of exports in the financial year 2022-23.

Canada is the Fourth-Largest Source of Foreign Tourists in India

Canada has consistently been one of the top source countries for foreign tourists in India. In 2021, the latest year for which data is available, Canada accounted for 5.3% of Foreign Tourist Arrivals (FTAs) in India, with 80,437 tourists. In 2017, Canada held a share of 3.4% of FTAs and was the fifth-largest source of tourists for India.

However, the number of tourists from Canada in 2021 was only a quarter of that in 2017. FTAs from Canada reached 3,51,859 in the pre-pandemic year of 2019 but fell sharply to 80,437 in 2021, a post-pandemic year. It's worth mentioning that while the number of foreign tourists from Canada dropped, the share of Canada in India's total foreign tourist arrivals increased, indicating an overall contraction in the total number of foreign tourists.

Source for All Data- IRCC, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, and Indian Tourism Statistics

Sikhs in Canada and India-Canada Tensions Over Khalistan Claims

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s statement in the House of Commons that Indian agencies were behind the murder of Canadian citizen Hardeep Singh Nijjar, a Sikh leader who held Khalistani views, has escalated tensions between India and Canada. According to Trudeau, Canadian intelligence agencies have information about Indian agencies’ involvement in Nijjar’s murder. He also said he told Prime Minister Narendra Modi about this during the G-20 Summit in Delhi, apart from having informed leaders of countries with close ties to Canada—the United States of America, Britain, France, and Australia. Trudeau has also said that the killing of a Canadian citizen by a foreign agency in his country challenges its sovereignty.

India has entirely and strictly rejected Trudeau’s allegations, calling them “absurd” and motivated. According to the Ministry of External Affairs, “Such baseless allegations are meant to divert attention from the Khalistani terrorists and radicals who have found refuge in Canada and threaten India’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. The Canadian government not taking any action in this matter has been a matter of concern for a long time.”

While the Canadian foreign ministry asked senior Indian diplomat, Pawan Kumar Rai, to leave the country, Trudeau has said he does not want to escalate tensions with India, but the Indian government must take Nijjar’s killing seriously. The Indian foreign ministry also asked Canadian diplomat Oliver Sylvester to leave the country. Canada advised its citizens not to visit ‘sensitive’ areas in India, and India asked its citizens in Canada to be alert and temporarily banned visa applications for Canadian citizens.

The United States, Britain and Australia have expressed concerns over the developments. However, all political parties in Canada—except Conservative leader Pierre Marcel Poilievre, who has demanded evidence from Trudeau—are with the Canadian government on this issue. The growing tensions between the two countries are a matter of concern for the people of Indian origin living in Canada. People with Khalistani notions do live in the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada, and India has put the Canadian government in the dock over this for many years—perhaps because the Air India conspiracy of 1985 was hatched on Canadian soil.

Stephen Harper, the Conservative Party prime minister of Canada, had visited India when Manmohan Singh was the prime minister. At the time, Minister of State for External Affairs Preneet Kaur had raised the issue of Khalistanis in Canada with him. Harper was still the prime minister during Modi’s first visit to Canada, but Modi has not visited Canada since the Liberal Party’s Trudeau became Prime Minister, first in 2015 and again in 2019. In 2018, during Trudeau’s first visit to India, the Indian government is believed to have displayed indifference towards him, reportedly over Canada’s “soft” attitude towards Sikh fundamentalists.

The Sikh community has a crucial place in Trudeau’s Cabinet, which, in 2018, had three Sikh ministers, including Defence Minister Sajjan Singh. Former Punjab chief minister Amarinder Singh had called Sajjan Singh a Khalistan supporter, a charge he had rejected, and he is still in Trudeau’s Cabinet. In 2018, a section of the Indian media also said Jaspal Atwal, who came with Trudeau to India, is Khalistani. But it has turned out since then that Atwal is a fan of Modi’s.

During the G-20 Summit, an allegedly heated exchange occurred between Modi and Trudeau, which the Indian media painted as a one-sided discussion led by the Indian Prime Minister. Reportedly, the discussion was over the actions of Sikh “separatists” in Canada, which Trudeau saw as India interfering in his internal affairs. He reportedly said in India that Canada believes in “democratic, pluralistic values and gives space to all kinds of ideas [but that he] will not tolerate violent activities”.

Trudeau was also stranded in India for two days because his private plane broke down. However, as soon as he reached his country, the news came that Canada had stopped its trade mission with India.

Hardeep Singh Nijjar

Forty-five-year-old Nijjar, originally from the Bhar Singh Pura village of the Jalandhar district, was president of the Guru Nanak Sikh Gurdwara of Surrey Delta and supporter of the Khalistani ideology. He had been in Canada since 1997 and was shot dead on 18 June at the gurudwara.

According to the Indian government, Nijjar headed the banned outfit, Khalistan Tiger Force, which is destroying India’s internal environment. The Indian government believes Nijjar was associated with Gurpatwant Singh Pannu’s banned organisation, Sikhs for Justice or SFJ. The National Investigation Agency declared Nijjar ‘most wanted’ and offered him a Rs 10 lakh cash reward.

On the other hand, people close to Nijjar say the Indian government has been tarnishing his character. A well-wisher of Nijjar, who lives in Sari, said on the condition of anonymity, “Though Nijjar supported Khalistani ideas, he was not a terrorist. He constantly spoke on human rights issues—not only the injustice to Sikhs but atrocities against other communities.”

After Nijjar’s death, his supporters demonstrated in many Canadian, American and British cities. Last July, pro-Khalistani organisations put up posters of some Indian ambassadors in Canada and appealed to target them. After this, India summoned the Canadian ambassador and expressed strong objections.

Others with Khalistani views have been killed before Nijjar, for which a section of Canadian Sikhs blame the Indian intelligence agencies. Last May, Khalistan supporter and one of India’s most wanted criminals, Paramjit Singh Panjwar, was murdered in Lahore, Pakistan. In 2017, Avtar Singh Khanda, a Khalistan supporter close to Waris Punjab De chief Amritpal Singh, died in a hospital in Birmingham, United Kingdom. Khalistan supporters say he was killed, while some reports attribute his death to blood cancer—the exact cause of his death remains unclear.

Babbar Khalsa leader Ripudaman Singh Malik—acquitted in 2005 of conspiracy charges in the 1985 Air India plane attack in which 331 people died—was shot dead in Surrey, Canada, on 15 June last year. This killing, too, remains a mystery. The Indian government had removed him from a ‘blacklist’, and he had openly praised Modi a few times. Many Sikhs in Canada—not just those Khalistan-backers—believed Malik was collaborating with the Indian authorities.

A few days before his death, in an interview with Gurpreet Singh, an Indian-origin Canadian journalist and radio broadcaster, Nijjar had expressed apprehensions about his safety. Gurpreet says: “After the murder of Paramjit Singh Panjwar in Pakistan, Nijjar issued a statement asking the Sikh community to be alert. He also offered ardas in the memory of Panjwar at Guru Nanak Sikh Gurudwara.”

In his last radio interview with Gurpreet, Nijjar said, “After Panjwar’s murder, all the Sikhs living here, people associated with human rights and especially those with Khalistan ideology need to be alert. The Indian government can get them killed... We will also ask Canadian government agencies to ensure our security. The Modi-Amit Shah duo has infiltrated Canadian politics for quite some time. People of their agencies have infiltrated our religious institutions… Ajit Doval himself has admitted that his agencies have their network spread in other countries.”

After Nijjar’s killing, his supporters petitioned the House of Commons to ask the Canadian government to investigate the incident and determine the role of Indian agencies. Online petitions to the House of Commons must have at least 500 signatures—this one sponsored by Liberal Party Member of Parliament Sukh Dhaliwal had around 1,000.

Speaking to this author, Sukh Dhaliwal said on Trudeau’s statement in the Canadian Parliament, “Our Prime Minister made it clear by making this statement that Canada is a sovereign country. No country can challenge our sovereignty by coming to our soil and taking such action.”

Before Trudeau’s statement in the House of Commons, prominent Canadian newspaper The Globe and Mail published a report citing anonymous government sources that said Canadian intelligence had solid “evidence” Indian agencies were behind Nijjar’s killing.

The editor of a Punjabi newspaper published in Toronto, Canada, says on condition of anonymity, “This matter can be seen from many perspectives. One thought is that just as the Modi government does politics on Hindutva and emotional issues to divert attention from the real issues, Trudeau may be a liberal leader, but his report card has been worsening for some time. By raising this issue, he would emerge as the guardian of Canada’s sovereignty and gain the Sikh community’s support, which, though small in number, holds an important position in Canada.”

The same editor says, “Even if Trudeau seeks political gains, we cannot deny that the Indian government, through its embassies, influences the diaspora’s cultural centres, like the gurdwaras, temples, etc. There are increased efforts to control the overseas Indian media through the embassies. Non-resident Indian journalists who express views against the Indian government are being silenced. The visas of those with dissenting views are restricted, or they are ‘blacklisted’ by the Indian government.”

He also says, “Very few harbour the Khalistan idea in Canada; and people with this viewpoint are in America, England, and Australia, too—so why does the Indian government only raise questions about Canada?

Gurpatwant Pannu, leader of the banned outfit SFJ, lives in America. To this, the editor says, “How many times has Modiji cornered the American President about this? Hindu fundamentalists are threatening secularists of Indian origin [in Canada]. Recently... those who wrote pro-Khalistan slogans at a temple in Australia turned out to be people with Hindutva thinking. Why did the Modi government never question this? Maybe these are their thoughts! The Khalistan idea is dead—no one wants it in Punjab, and very few support Khalistani ideas in Canada or other countries. The Modi government keeps the word ‘Khalistan’ alive to keep communal politics going. Punjabis settled in Canada raised a strong voice for the farmer movement—perhaps it is taking revenge for the same.”

In April 2020, a Canadian media group Global News reported that Indian intelligence agency ‘RAW’ tried to influence Canadian politics through a journalist. The Quint later reported the findings of a related court case.

Senior Canadian journalist Gurpreet Singh says, “I disagree that Trudeau is trying to please the Sikhs or that he is against India. Canada’s Sikhs are only 2% of the population, and not all are Khalistani thinkers. More Hindus live here than Sikhs, so why would Trudeau want Hindu voters to turn against him? So far, Trudeau’s relationship with the Modi government has been friendly. He has been accused of speaking out on human rights violations in other countries but not taking a strong stance on India.

“His cabinet has ministers like Anita Anand, who admire Modi. His Liberal Party Member of Parliament Chandra Arya is [pro-]Hindutva. Trudeau never objected to them. He did not just give a statement in Parliament, but told Modi about the activities of Indian agencies in Canada and also spoke with his allies, as a Canadian newspaper has reported. He did what a leader of any country would have done in this situation.”

The former Canadian Health Minister and former chief minister (premier) of British Columbia State, Ujjal Dosanjh, a known staunch anti-Khalistani, told Global News in an interview that it is “unbelievable” but “not entirely out of the question” that Indian agencies had a hand in the Nijjar affair. He seems to believe India is no longer the country he left; and a lot changed after Modi’s arrival.

Tensions between the countries have left people of Indian origin in Canada a worried lot. The students applying for visas and their parents are especially anxious, though experts believe they need not be. A 2002 report said more than 40% of international students in Canada are Indians.

Gurpreet Singh says, “There is greater uneasiness among the Indian community living in Canada. They worry about how the deterioration in relations will affect immigration and visas. There are person-to-person relations between residents of India and Canada, and travel is its mainstay.”

Canada is also one of 17 countries with which India has the most trade. Reuters has reported that 30 Indian companies including TCS, Infosys, and Wipro have invested billions in Canada, and employ thousands of people.

But Punjab-based economist Sucha Singh Gill is optimistic. He says, “Considering their deep relations, I do not think this bitterness will last long. Both countries are very inter-dependent. We have seen how even when tensions escalate some countries continue their trade through third parties—I don’t think business will be affected much.”

The author is an independent journalist. The views are personal.