American robins now migrate 12 days earlier than in 1994

Every spring, American robins migrate north from all over the U.S. and Mexico, flying up to 250 miles a day to reach their breeding grounds in Canada and Alaska. There, they spend the short summer in a mad rush to find a mate, build a nest, raise a family, and fatten up before the long haul back south.

Now climate change is making seasonal rhythms less predictable, and springtime is arriving earlier in many parts of the Arctic. Are robins changing the timing of their migration to keep pace, and if so, how do they know when to migrate? Although many animals are adjusting the timing of their migration, the factors driving these changes in migratory behavior have remained poorly understood.

A new study, published in Environmental Research Letters, concludes that robin migration is kicking off earlier by about five days each decade. The study is also the first to reveal the environmental conditions along the migration route that help the birds keep up with the changing seasons. Lead author Ruth Oliver completed the work while earning her doctorate at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

At Canada's Slave Lake, a pit stop for migrating birds, researchers have been recording spring migration timing for a quarter century. Their visual surveys and netting censuses revealed that robins have been migrating about five days earlier per decade since 1994.

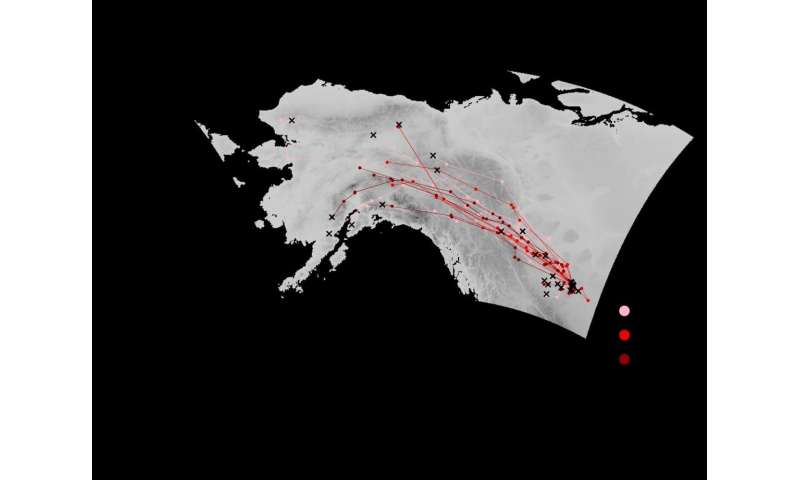

In order to understand what factors are driving the earlier migration, Oliver and Lamont associate research professor Natalie Boelman, a coauthor on the paper, knew they needed to take a look at the flight paths of individual robins.

Their solution was to attach tiny GPS "backpacks" to the birds, after netting them at Slave Lake in mid-migration. "We made these little harnesses out of nylon string," Oliver explained. "It basically goes around their neck, down their chest and through their legs, then back around to the backpack." The unit weighs less than a nickel—light enough for the robins to fly unhindered. The researchers expect that the thin nylon string eventually degrades, allowing the backpacks to fall off.

The researchers slipped these backpacks onto a total of 55 robins, tracking their movements for the months of April through June. With the precise location from the GPS, the team was able to link the birds' movements with weather data on air temperature, snow depth, wind speed, precipitation, and other conditions that might help or hinder migration.

The results showed that the robins start heading north earlier when winters are warm and dry, and suggest that local environmental conditions along the way help to fine-tune their flight schedules.

"The one factor that seemed the most consistent was snow conditions and when things melt. That's very new," said Oliver. "We've generally felt like birds must be responding to when food is available—when snow melts and there are insects to get at—but we've never had data like this before."

Boelman added that "with this sort of quantitative understanding of what matters to the birds as they are migrating, we can develop predictive models" that forecast the birds' responses as the climate continues to warm. "Because the timing of migration can indirectly influence the reproductive success of an individual, understanding controls over the timing of migratory events is important."

For now, it seems as though the environmental cues are helping the robins to keep pace with the shifting seasons. "The missing piece is, to what extent are they already pushing their behavioral flexibility, or how much more do they have to go?" said Oliver.

Because the study caught the birds in mid-migration, the tracking data doesn't reflect the birds' full migration path. To overcome this limitation, the researchers plan to analyze tissue from the robins' feathers and claws, which they collected while attaching the GPS harnesses, to estimate where each bird spent the previous winter and summer.

Over the long term, Oliver says, she hopes to use the GPS trackers to sort out other mysteries as well, such as how much of the change in migration timing is due to the behavioral responses found in the study versus natural selection to changing environments, or other factors.

"This type of work will be really cool once we can track individuals throughout the course of their life, and that's on the near-term horizon, in terms of technological capabilities," she said. "I think that will really help us unpack some of the intricacies of these questions."Fifty years of data show new changes in bird migration

More information: Ruth Y Oliver et al, Behavioral responses to spring snow conditions contribute to long-term shift in migration phenology in American robins, Environmental Research Letters (2020). DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/ab71a0

Journal information: Environmental Research Letters

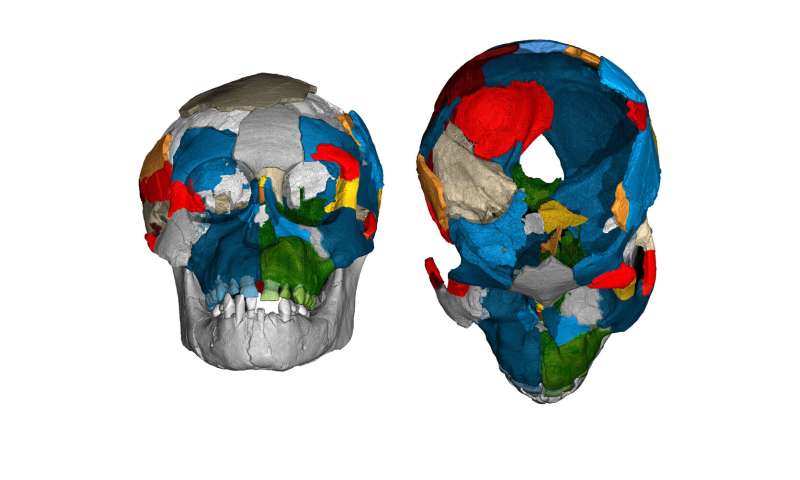

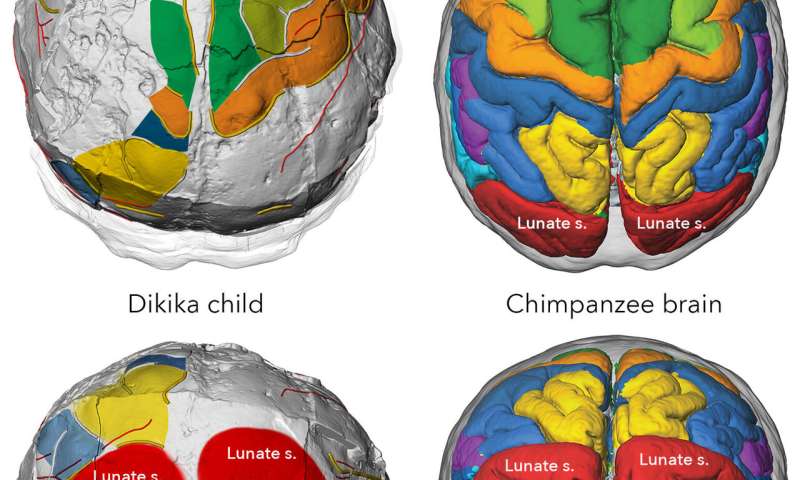

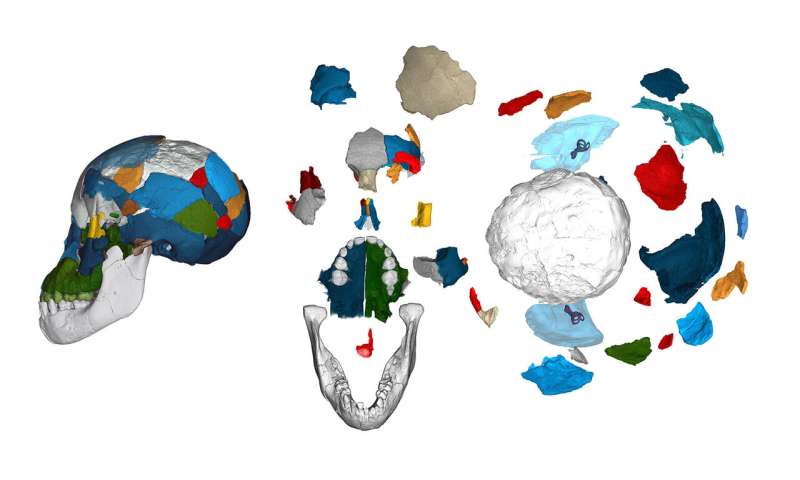

Brain imprints (shown in white) in fossil skulls of the species Australopithecus afarensis shed new light on the evolution of brain growth and organization. Several years of painstaking fossil reconstruction, and counting of dental growth lines, yielded an exceptionally preserved brain imprint of the Dikika child, and a precise age at death. Credit: Philipp Gunz, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Brain imprints (shown in white) in fossil skulls of the species Australopithecus afarensis shed new light on the evolution of brain growth and organization. Several years of painstaking fossil reconstruction, and counting of dental growth lines, yielded an exceptionally preserved brain imprint of the Dikika child, and a precise age at death. Credit: Philipp Gunz, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0