HWY. BR-319: The beginning of the end for Brazil’s Amazon forest (commentary)

Commentary by Philip M. Fearnside on 3 November 2020

Brazil’s planned reconstruction of the BR-319 (Manaus-Porto Velho) Highway paralleling the Purus and Madeira rivers would give deforesters access to about half of what remains of the country’s Amazon forest, and so is perhaps the most consequential conservation issue for Brazil today.

The highway route is essentially a lawless area today, and the lack of governance is a critical issue in the battle over licensing the highway reconstruction project.

The BR-319 upgrade would link the current “arc of deforestation” to central Amazonia, allowing movement of deforestation actors to all forest locations with road links to Manaus, while a planned BR-319 connecting road would open the vast forest area between the BR-319 and the Peruvian border.

The BR-319 Environmental Impact Assessment has many flaws, including ignoring impacts beyond those adjacent to the highway. The EIA also contains passages admitting to some disastrous project impacts. This post is a commentary. The views expressed are those of the author, not necessarily Mongabay

The text of this commentary is updated from an earlier Portuguese-language version of the author’s column at Amazônia Real.

The BR-319 (Manaus-Porto Velho) Highway was built in the early 1970s by Brazil’s military dictatorship, but was abandoned in 1988. In 2016, a “maintenance” program was authorized, and the highway is now passable during the dry season.

The currently proposed “Reconstruction” of BR-319, which would build a new paved road atop the old dirt roadbed, is certainly among the most consequential decisions facing Brazil today. The environmental impact assessment (EIA) for the project has been submitted to the licensing agency (IBAMA, Brazil’s environmental agency), where it is receiving accelerated treatment for what appears to be a foreordained approval. The hasty authorization of a project that implies a major expansion of the area in Amazonia that is exposed to deforestation is extremely unwise.

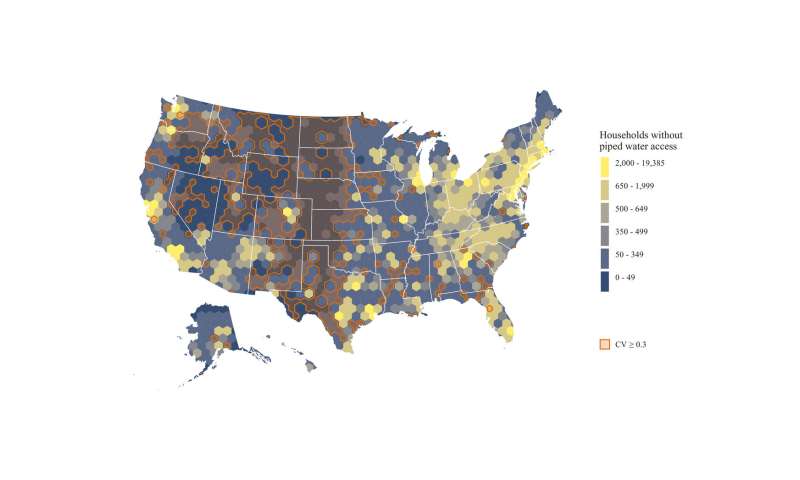

So far, deforestation has been almost entirely limited to the “arc of deforestation” along the southern and eastern edges of the Amazon forest in Brazil, and to the eastern half of the region where road access is already implanted.

Large-scale impacts

The impact of the BR-319 will extend far beyond the strip along the highway route that is the subject of the EIA.

The BR-319 opens the central and northern portions of Amazonia to the migration of land grabbers (grileiros), loggers, cattlemen, individual squatters (posseiros) and organized landless farmers (sem-terras). These actors are already present in the “arc of deforestation” and have moved into areas in the southern portion of the state of Amazonas where there is road access, including Apuí, Igarapé Realidade and Lábrea (see black and white map below).

Critically, BR-319 is associated with plans for additional roads, such as AM-366, that would open the vast area of intact rainforest in the western part of the state of Amazonas.

Opening this “Trans-Purus” region in western Amazonas to deforestation would be catastrophic for Brazil, leading to loss of critical environmental services. These include water supply to the city of São Paulo: the Trans-Purus area is the last great block of intact forest in Brazilian Amazonia, and losing this area means losing the Amazon forest’s function of recycling the water that is carried in the “flying rivers” to Brazil’s major urban and agricultural areas (see here, here, here, here and here). Amazonia is supplying 70% of the water during the peak of the rainy season in São Paulo, when the reservoirs that supply the city fill. São Paulo has nearly run out of water several times, even with Amazonia’s water cycling function still intact.

The environmental impact assessment (EIA) for reconstructing the “middle stretch” of the BR-319 is now publicly available. The EIA defines an “area of direct impact” (ADA) and an “area of indirect impact” (AIA) that excludes the wider impacts of the highway, including the critical “Trans-Purus” region to the west of the Purus River.

Despite the many deficiencies of the EIA, buried in the document’s 3735 pages there are passages that recognize many of the project’s true impacts, for which the authors should be congratulated. Among these is the threat that reconstructing the BR-319 poses to the Trans-Purus region by unleashing a chain of events that would result in opening the planned AM-366 road, thus allowing deforesters to enter this critical region:

The repaving and full operation of the BR-319 along its entire length may encourage regional politicians to pressure the government of Amazonas to resume the project to implement the AM-366 highway. This risk is very concrete in that, a few years after the opening of BR-319, a “picadão” [big trail] linking BR-319 to the city of Tapauá was opened by an initiative that was probably from private agents. (ECI-Apurina, p. 119).

The EIA also mentions the relevance of Brazil’s current presidential administration to the increased danger of the AM-366 being built:

In the political-institutional conditions now present in the region and in the country, added to the initiatives of the executive branch of the federal government to review environmental protection measures and to facilitate the advance of agribusiness in southern Amazonas — as previously noted — it is quite possible that the AM-366 could obtain sufficient political support for its implementation. (ECI-Apurina, p. 119).

The potential for invasion of the areas opened up by the AM-366 road and the illegal side roads along its route between Tapauá and the BR-319 is mentioned:

[AM-366] would offer migrants from the south and southeast regions, and especially those from Rondônia, an open route for opening lots in government lands — at zero cost. (ECI-Apurina, p. 83).

The EIA also mentions the likelihood of the AM-366 sprouting side roads (ramais) to provide access to oil and gas production areas planned for exploitation under the massive “Solimões Sedimentary Area Project”:

The question of the exploration of the blocks in the Solimões [Upper Amazon] basin. ,,, gains greater relevance due precisely to the possible interconnection between the BR-319 and the municipalities of Tefé and Coari via the AM-366 highway, from which ramais [side roads] could “branch off” to the locations of the oil installations … (ECI-Apurina, p. 106).

Illegal side roads (ramais) branching off BR-319 are already being built, such as one begun in February 2020 entering a protected area, the Lago do Capanã Grande Extractive Reserve. There are also illegal roads being built in the opposite direction, starting from towns on the Purus River and progressing towards the BR-319. In addition to the illegal side road being built from Tapauá (ECI-Apurina, pp. 119-121), the EIA mentions a similar illegal road being built to connect Canutama to the BR-319, which is already 40 kilometers long (EIA, p. 2565). The obvious lack of governance in the area is a key issue in the battle over licensing.

The oil and gas project is a major threat to the forests of the Trans-Purus region because the scale of the project means that the companies exploiting the oil and gas would have a major motive for pressuring the government to provide road access.

The EIA touches on the responsibility of DNIT, Brazil’s National Department of Transportation Infrastructure, for the disastrous outcome that would result from the BR-319’s role in increasing the likelihood of the AM-366 being built:

….this chain of events…, in a certain way, gives the entrepreneur some degree of responsibility for the eventual terrestrial connection of BR-319 to the city of Tapauá …. (ECI-Apurina, p. 120).

Despite some passages in the EIA recognizing the BR-319’s wider impact, this does not translate into recommendations about what to do about it. Instead, the focus is restricted to the ADA and AIA, and the recommendations are limited to pointing out that governance is needed to minimize impacts. Questioning the existence of the project, or delaying it for a substantial period of years while governance is established, are not presented as serious options.

Instead, the recommendations for avoiding the massive impacts are limited to the standard call for “governance,” but the chances of such a program being implemented on a scale that would avoid disaster are near zero. The BR-319 area is essentially lawless today, with land grabbing (grilagem) and illegal land invasions, logging and building of side roads occurring with impunity. It is simply fictitious that “BR-319 will be an example of sustainability for the World,” as the members of the Legislative Assembly of the state of Amazonas claim.

Impacts on Indigenous peoples

The Indigenous component is critical. This project element was apparently submitted to the licensing agency (IBAMA) some time after the rest of the EIA. Although the separation in time was relatively short in this case, it is an important irregularity, repeating the scandal that surrounded the 2015 EIA for the São Luis do Tapajós Dam. As with that controversial dam, the Relatório de Impacto Ambiental (RIMA), which is the document that serves for public discussion of the BR-319 project (including the public hearings), was obviously completed before the Indigenous component was available and contains no information on Indigenous peoples.

The question of consultation of Indigenous peoples affected by the BR-319 highway project represents a key test of Brazil’s legal system. Brazil’s Federal Public Ministry (a public prosecutor’s office established by Brazil’s 1988 constitution to defend the rights of the people) has long been trying to bring the rule of law to Brazil in this regard, but these efforts have so far failed, as in the cases of the Belo Monte and São Manoel Dams (see here, here and here).

The EIA for the BR-319 mentions the fact that Brazilian law and Convention 169 of the International Labour Organization (ILO-169), of which Brazil is a signatory, require prior consultation of affected Indigenous peoples. This legally required consultation needs to not only occur before the construction work begins, but rather before any decision is made on whether or not to go ahead with the project:

And Article 15 of the Convention makes it explicit that this consultation must take place before governments undertake or authorize any program for prospecting or exploiting resources that exist in the habitat of Indigenous peoples. (ECI-Apurina, p. 27).

In the case of BR-319, no Indigenous people have been consulted, despite the project’s bidding already having been opened and its initiation being immanent in violation of ILO-169 and by Brazilian law (10.088, de 5 de novembro de 2019, formerly 5.051, de 19 de abril de 2004), which implements the convention.

However, DNIT plans to do its “consultation” while the road construction is underway. The plan is to only consult five Indigenous areas, despite the road’s impact extending much farther. IBAMA’s internal regulations (Portaria Interministerial Nº 419, de 26 de outubro de 2011, Anexo II) consider all Indigenous areas within 40 kilometers of a highway in Amazonia to be “directly impacted” and requires them to be included in the Indigenous component of the EIA. In the case of the entire BR-319 highway (not only the “middle stretch”), there are 13 Indigenous areas within the 40-kilometer limit.

Reconstruction of the middle stretch is what would trigger the socio-environmental impacts from the entire road by opening the floodgates for traffic and migration. ILO-169 and its replication in Brazilian law have no distance limit for impacts requiring consultation. These impacts clearly go far beyond the area considered in the EIA. In addition to adversely affecting Indigenous peoples already living within the areas of migration flow that the highway would stimulate, such as those in the state of Roraima, deforestation from the highway route itself can spread far beyond 40 kilometers. If a 150-kilometer limit is considered, 63 Indigenous areas would be considered impacted.

In conclusion, reconstructing the BR-319 highway would have enormous impacts and few benefits. In addition to the need to comply with legal requirements such as obtaining the free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous peoples, Brazil’s leaders should pause to consider the wisdom of the project itself, given the threat it represents to the country’s national interests. Risking the loss of Amazonia’s environmental services, such as supplying water to São Paulo, is no small matter for Brazil.