From 49.6C in Canada to 53.2C in Kuwait, Al Jazeera looks at where the hottest places are on Earth.

By Mohammed Haddad

1 Jul 2021

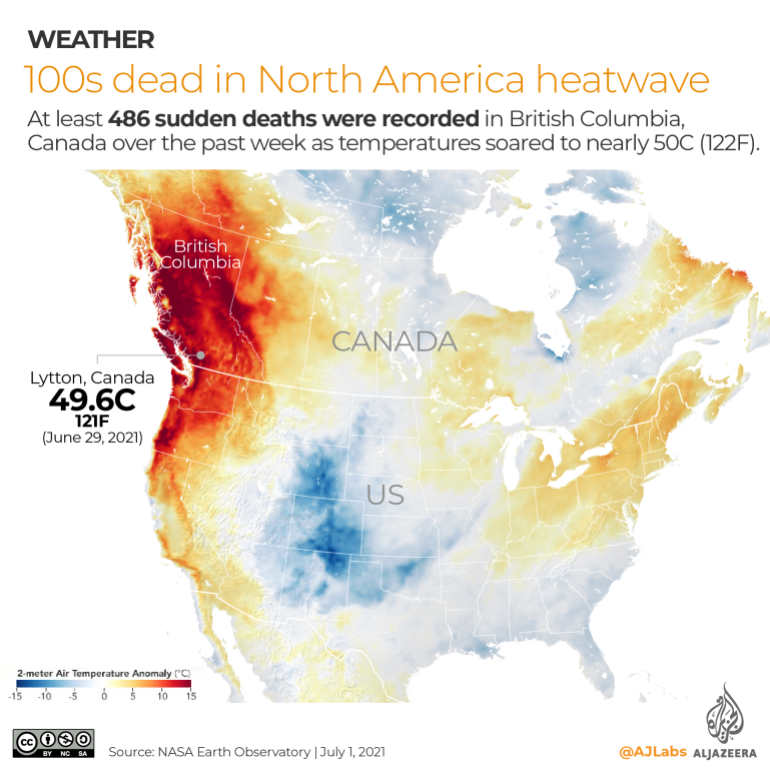

June was an exceptionally hot month for several countries in the northern hemisphere. Since Friday June 25, at least 486 sudden deaths have been recorded in Canada’s British Columbia province as temperatures soared to nearly 50C (122F). In the United States, the ongoing heatwave has buckled highways and melted power lines. A so-called “heat dome”, where high pressure traps the heat, is being blamed for the excessively high temperatures.

Record-breaking temperatures

On June 29, Lytton, a small town about 200km (124 miles) from Vancouver, hit 49.6C (121F), setting a national record for the highest temperature ever recorded across Canada. Schools, universities and vaccination centres were closed across British Columbia.

Just south of the border in the US state of Oregon, the city of Portland hit an all-time high of 46.6C (116F), breaking the previous high of 41.6C (107F), first set in 1965.

Kuwait – the hottest place on Earth in 2021

On June 22, the Kuwaiti city of Nuwaiseeb recorded the highest temperature in the world so far this year at 53.2C (127.7F). In neighbouring Iraq, temperatures reached 51.6C (124.8F) on July 1, 2021, with Omidiyeh, Iran, not far behind with a maximum temperature of 51C (123.8F) recorded so far. Several other countries in the Middle East, including the United Arab Emirates, Oman and Saudi Arabia, recorded temperatures higher than 50C (112F) in June.

The Gulf is known for its hot and humid climate with temperatures regularly exceeding 40C (104F) in the summer months.

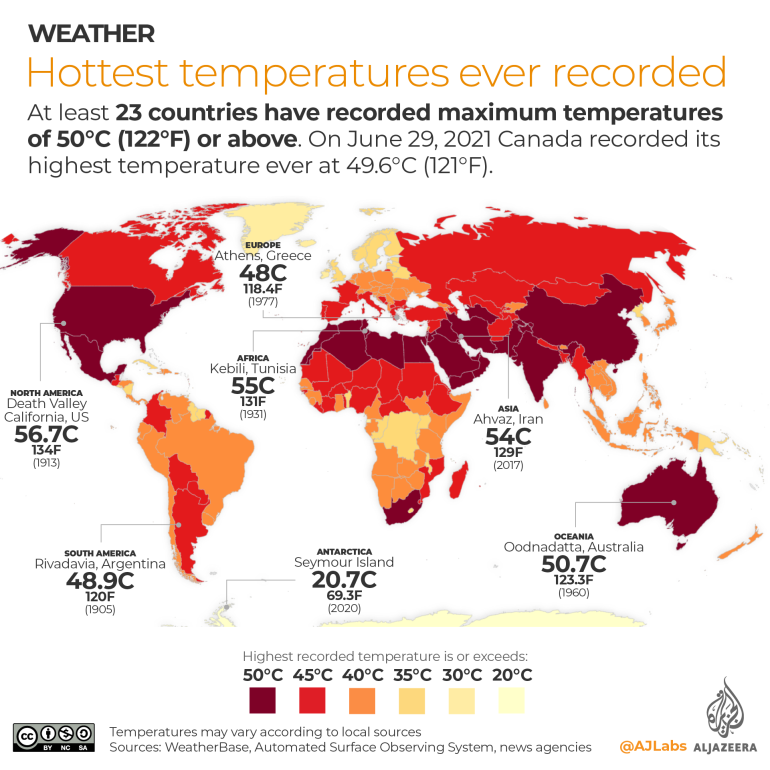

Hottest temperatures ever recorded

The map below shows the hottest temperatures ever recorded in each country around the world. At least 23 countries have recorded maximum temperatures of 50C (122F) or above.

Currently, the highest officially registered temperature is 56.7C (134F), recorded in California’s Death Valley back in 1913. The hottest known temperature in Africa is 55C (131F) recorded in Kebili, Tunisia in 1931. Iran holds Asia’s hottest official temperature of 54C (129F) which it recorded in 2017.

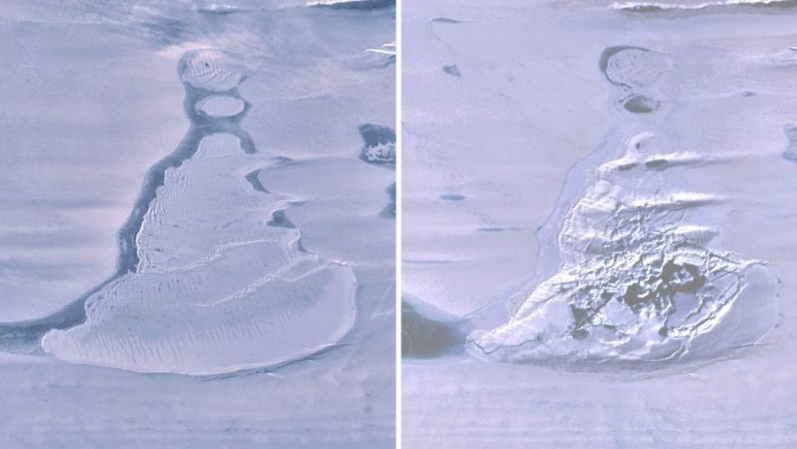

In 2020, Seymour Island in Antarctica recorded a maximum temperature of 20.7C (69.3F). According to the United Nations’ World Meteorological Organization (WMO), temperatures on the Antarctic Peninsula have risen by almost 3C (5.4F) over the past 50 years.

How temperature is measured

The temperature that you see on the news or on the weather app on your phone relies on a network of weather stations positioned around the globe. To ensure accurate readings, weather stations use specialist platinum resistance thermometers placed in shaded instruments known as a Stevenson screen at a height of 1.25-2 metres (4-6 feet) above the ground.

There are two well-known scales used to measure temperature: Celsius and Fahrenheit. Only a few countries, including the US, use Fahrenheit as their official scale. The rest of the world uses the Celsius scale named after Swedish astronomer Anders Celsius who invented the 0-100 degree freezing and boiling point scale in 1742.

The world is getting hotter

A report published by NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) found that the Earth’s global average surface temperature in 2020 tied with 2016 as the warmest year on record.

GISS Director Gavin Schmidt said, “The last seven years have been the warmest seven years on record, typifying the ongoing and dramatic warming trend. Whether one year is a record or not is not really that important – the important things are long-term trends. With these trends, and as the human impact on the climate increases, we have to expect that records will continue to be broken.”

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/world/2021/07/01/arctics-last-ice-area-shows-earlier-than-expected-melt/20210701110736-60dde1b425fc7a41a397fcbdjpeg.jpg)