Capturing CO2 with electricity: A microbial enzyme inspires electrochemistry

Scientists isolate a microbial enzyme and branch it on an electrode to efficiently and unidirectionally convert CO2 to formate

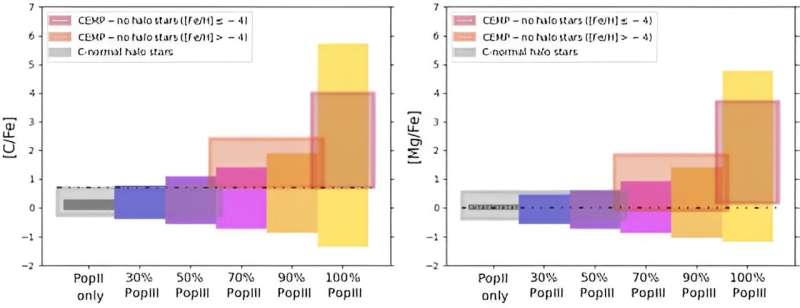

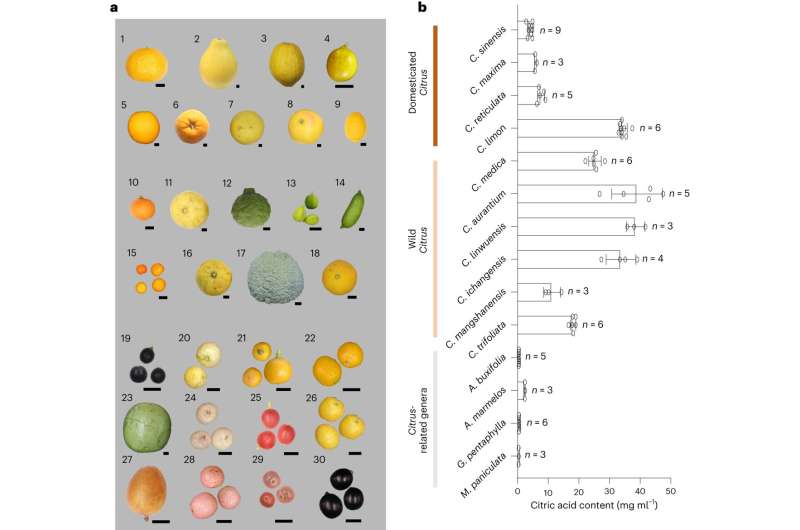

IMAGE: THE GAS CONVERSION PROCESS BY AN ELECTRODE-BASED ENZYMATIC REACTION. THE ENZYME EXTRACTED FROM THE MICROBE, BOUND TO A GRAPHITE ELECTRODE, CAN BE EMPLOYED TO CONVERT THE GREENHOUSE GAS CARBON DIOXIDE TO FORMATE, A MOLECULE THAT CAN BE USED AS SAFE ENERGY STORAGE OR AS A BASIS FOR CHEMICAL SYNTHESIS. THE TWO MOLECULES ARE SHOWN AS BALLS AND STICKS (CARBON ATOMS IN GREY, OXYGEN ATOMS IN RED). THE STRUCTURE OF THE PROTEIN FROM THE METHANOGEN METHANOTHERMOBACTER WOLFEII IS SHOWN AS A LIGHT BLUE SURFACE TO ILLUSTRATE THE ENZYME. THE ENERGY REQUIRED BY THE ELECTRODE CAN ORIGINATE FROM RENEWABLE ENERGY SOURCES. view more

CREDIT: O. LEMAIRE, M. BELHAMRI AND T. WAGNER/ MAX PLANCK INSTITUTE FOR MARINE MICROBIOLOGY

Seeking microorganisms that efficiently capture the greenhouse gas CO2

“The enzymes employed by the microorganisms represent a fantastic playground for scientists as they allow highly specific reactions at fast rates”, says Tristan Wagner, head of the Max Planck Research Group Microbial Metabolism at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology (MPIMM). Some of these enzymes have an interesting way of capturing CO2: They transform it into formate, a stable and safe compound that can be used to store energy or to synthesize various molecules for industrial or pharmaceutical purposes. One example is Methermicoccus shengliensis, a methanogen (a microbe producing methane) isolated from an oilfield and growing at 50 °C. It has been cultivated and studied over the past years by Julia Kurth and Cornelia Welte at Radboud University in the Netherlands. At the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Olivier Lemaire, Mélissa Belhamri and Tristan Wagner dissected the microbe to find its CO2-capturing enzyme and measure how fast and efficiently it can transform CO2.

A CO2-converting enzyme with great potential

The Max Planck-scientists undertook the challenging task to isolate the microbial enzyme. “Since we knew that such enzymes are sensitive to oxygen, we had to work inside an anaerobic tent devoid of ambient air to separate it from the other proteins – quite complicated, but we succeeded”, says Olivier Lemaire. Once isolated, the scientists characterized the enzyme’s properties. They showed that it efficiently generates formate from CO2 but performs the reverse reaction at very slow rates and poor yield. “Similar enzymes belonging to the family of formate dehydrogenases are well known to operate in both directions, but we showed that the enzyme from Methermicoccus shengliensis is nearly unidirectional and could not efficiently convert the formate back into CO2”, reports Mélissa Belhamri. “We were quite thrilled by this phenomenon, occurring only in the absence of oxygen”, she adds. “Since the formate generated from CO2-fixation cannot be transformed back and therefore accumulates, such a system would be a highly interesting candidate for CO2-capture, especially if we could branch it on an electrode”, Tristan Wagner points out. The advantage of that: With the enzyme naturally or chemically attached to an electrode, the “energy” required to capture the CO2 will be directly delivered by the electrode, without electric current loss or the need for expensive or toxic chemical compounds as relays. Consequently, the enzyme-bound electrodes are efficient and attractive systems for gas conversion procedures. Thus, the purified enzyme was sent to the University of Geneva to set up an electrode-based CO2-capture system.

Electricity-based gas conversion

Selmihan Sahin and Ross Milton from the University of Geneva are specialists in electrochemistry. They use electrodes connected to electric current to perform chemical reactions. The electrode-based formate generation from CO2 often requires polluting and rare metals, and that is why they tried to replace these metals with the enzyme extracted in the group of Tristan Wagner at the MPIMM. The procedure of enzyme binding on an electrode is not always as efficient as expected, but the enzyme from Wagner’s research group has specific characteristics that could facilitate the process. The scientists from Switzerland managed to fix the enzyme on a graphite electrode, where it performed the gas conversion. The measured rates were comparable to those obtained with classic formate dehydrogenases. “The strength of this biological system coupled to the electrode lies in its efficiency in transferring the electrons from the electricity towards CO2 transformation”, highlights Lemaire. Sahin and Milton also confirmed that the system performs the reverse reaction poorly, as previously observed in the reaction tube. Consequently, the modified electrode continuously converted the greenhouse gas to formate without any detectable side-products generated or electric current loss.

Towards a new solution for atmospheric CO2 utilization

The collaborative work provides a new molecular tool to the scientific community: An enzyme converting CO2 by transferring electricity with high efficiency. Renewable green energy (e.g., wind or solar) could provide electricity to the electrode-based system that would turn CO2 into formate, a molecule directly usable for applications or to store energy. “Before us, no one ever tried to study an enzyme from such a methanogen for an electrode-based gas conversion”, says Tristan Wagner. “Yet, methanogens are natural outstanding gas converters”. As powerful as they could be, employing enzymes for large-scale processes would also require similar-scale enzyme production systems, a considerable investment. Therefore, while the discovered strategy could, in theory, significantly improve CO2 transformation, a deep knowledge of the enzyme mechanism is necessary before its application, and the team of researchers will now have to dissect in depth the molecular secrets of the reaction.

JOURNAL

Angewandte Chemie International Edition

ARTICLE TITLE

Bioelectrocatalytic CO2 Reduction by Mo-Dependent Formylmethanofuran Dehydrogenase

![The distribution of stars in our galaxy. Credit: NASA, ESA, and A. Feild [STScI] We can't see the first stars yet, but we can see their direct descendants](https://scx1.b-cdn.net/csz/news/800a/2023/we-cant-see-the-first-1.jpg)