"So much for 'building back better' and a 'green recovery,'" said youth climate leader Greta Thunberg.

An aerial view shows Marathon Petroleum Corporation's Los Angeles refinery on April 22, 2020. (Photo: David McNew/Getty Images)

Climate campaigners and energy experts are responding to a recent rise in fossil fuel demand by reiterating the necessity of rapidly transitioning to renewable sources like solar and wind, with Swedish activist Greta Thunberg warning Monday that "we are still speeding in the wrong direction."

Thunberg yet again took aim at world leaders' empty promises to combat the climate emergency, including through policies and investments provoked by the Covid-19 pandemic. As she put it: "So much for 'building back better' and a 'green recovery.'"

The 18-year-old—whose solo protests outside the Swedish Parliament sparked the global youth-led Fridays for Future movement—was reacting on Twitter to new reporting from Reuters that demand for coal and gas has topped pre-coronavirus highs, "with oil not far behind, dealing a setback to hopes the pandemic would spur a faster transition to clean energy."

Reuters highlighted figures from the International Energy Agency (IEA), the global energy watchdog which made clear in May that countries' current climate pledges are deeply inadequate and allowing new fossil fuel projects is incompatible with the global goal to dramatically cut planet-heating pollution.

Three-quarters of the world's total energy demand is still met by fossil fuels and both coal and gas demand are projected to surpass 2019 levels, according to the IEA. Coal demand is expected to rise 4.5% this year and gas demand is on track to increase 3.2%, after falling 1.9% last year.

As the news agency reported:

Global natural gas shortages, record gas and coal prices, a power crunch in China, and a three-year high on oil prices all tell one story—demand for energy has roared back and the world still needs fossil fuels to meet most of those energy needs.

"The demand fall during the pandemic was entirely linked to governments' decision to restrict movements and had nothing to do with the energy transition," Cuneyt Kazokoglu, head of oil demand analysis at FGE told Reuters.

"The energy transition and decarbonization are decade-long strategies and do not happen overnight."

Fatih Birol, head of the Paris-based IEA, has recently not only agreed with the consultant's analysis but also made a case for transitioning power systems.

Faced with a steep rise in European gas prices last month, Birol said in a statement that "it is inaccurate and misleading to lay the responsibility at the door of the clean energy transition."

"Today's situation is a reminder to governments, especially as we seek to accelerate clean energy transitions, of the importance of secure and affordable energy supplies—particularly for the most vulnerable people in our societies," Birol added. "Well-managed clean energy transitions are a solution to the issues that we are seeing in gas and electricity markets today—not the cause of them."

"Well-managed clean energy transitions are a solution to the issues that we are seeing in gas and electricity markets today—not the cause of them."

—Fatih Birol, IEA

Reporting last week on the rising demand for gas and its impact on electricity bills and factories, The New York Times noted that "growing concerns about climate change, expressed by shareholders or via court cases like the decision by a Dutch court in May ordering Royal Dutch Shell to cut greenhouse-gas emissions, may make some companies hesitate to invest in new multibillion-dollar fossil fuel projects."

While one expert at the consultancy Rystad Energy suggested that such hesitancy could lead to "more volatile" markets, the Times added that a shift to power from clean sources like wind and solar eventually "may help protect consumers from the tyranny of the global commodity markets," though "the events of this fall suggest that goal is some distance away."

In response to that report, some experts called for speeding up the transition to clean energy and storage rather than clinging to gas. The Times coverage came as youth climate leaders, including Thunberg and Ugandan activist Vanessa Nakate, marched through Milan, Italy.

That march followed the United Nations-sponsored Youth4Climate summit that featured speeches from Thunberg and Nakate, and was held to craft proposals for attendees of the U.N. conference known as COP 26, set to begin in Glasgow, Scotland later this month.

"'Build back better.' Blah blah blah," Thunberg said in her address. "This is all we hear from our so-called leaders. Words—words that sound great but so far have led to no action. Our hopes and dreams drowned in their empty words and promises."

Oct 5, 2021

David R Baker, Stephen Stapczynski, Dan Murtaugh and Rachel Morison, Bloomberg News

The world is living through the first major energy crisis of the clean-power transition. It won’t be the last.

The shortages jolting natural gas and electricity markets from the U.K. to China are unfolding just as demand roars back from the pandemic. But the planet has faced volatile energy markets and supply squeezes for decades. What’s different now is that the richest economies are also undergoing one of the most ambitious overhauls of their power systems since the dawn of the electric age -- with no easy way to store the energy generated from renewable sources.

The transition to cleaner energy is designed to make those systems more resilient, not less. But the actual switch will take decades, during which the world will still rely on fossil fuels even as major producers are now drastically shifting their output strategies.

“It is a cautionary message about how complex the energy transition is going to be,” said Daniel Yergin, one of the world’s foremost energy analysts and author of The New Map: Energy, Climate and the Clash of Nations.

In the throes of fundamental change, the world’s energy system has become strikingly more fragile and easier to shock.

RECIPE FOR VOLATILITY

Take the turmoil in Europe. After a colder-than-normal winter depleted natural gas inventories, gas and electricity prices soared as demand from rebounding economies surged too fast for supplies to match. Something similar probably would have happened had COVID-19 struck 20 years ago.

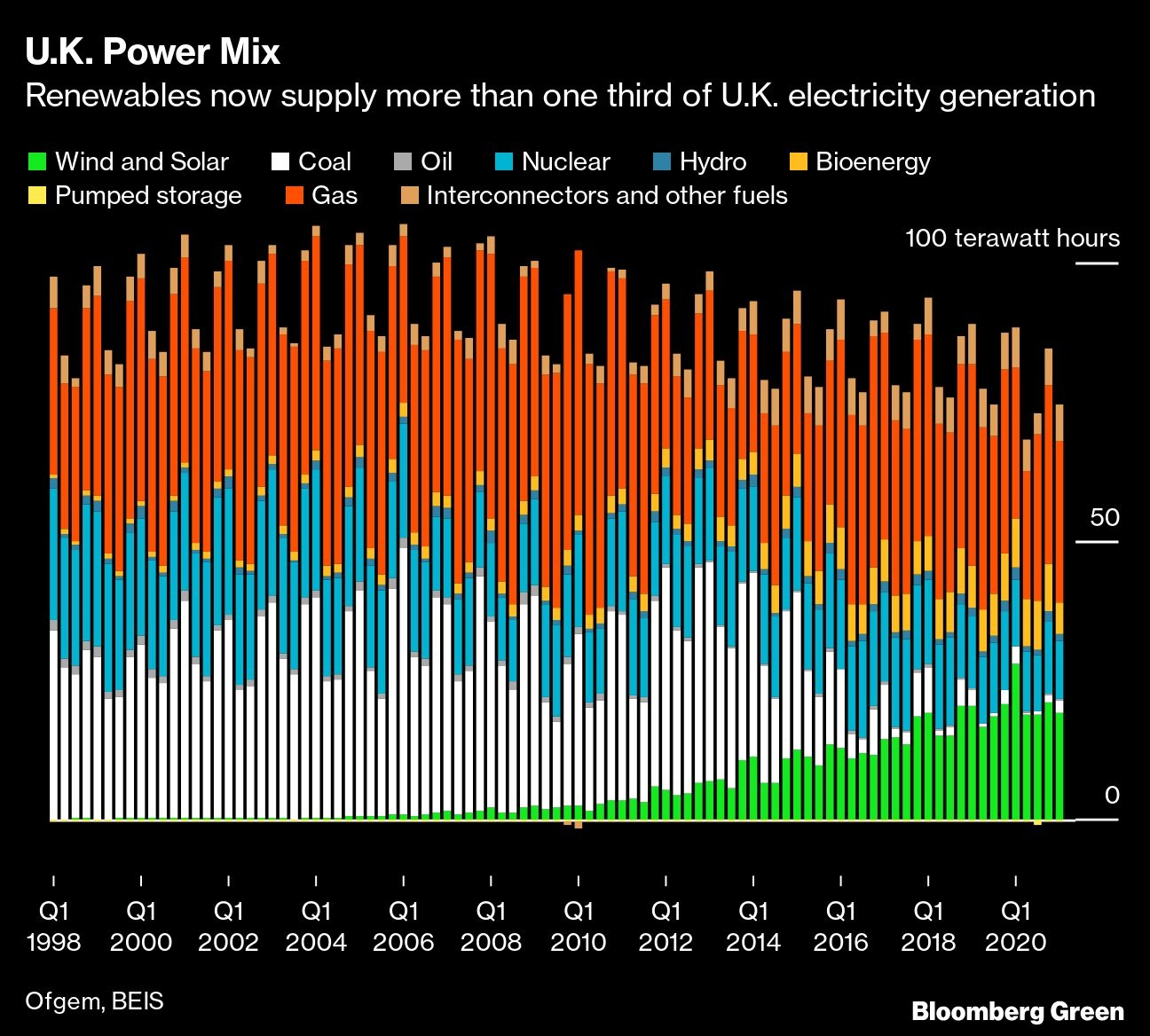

But now, the U.K. and Europe rely on a very different mix of energy sources. Coal has been cut back drastically, replaced in many instances by cleaner-burning gas. But surging global demand this year has left gas supplies scarce. At the same time, two other sources of power -- wind and water -- have had unusually low output, thanks to unexpectedly slower wind speeds and low rainfall in areas including Norway.

In other words: A strained global gas market triggered Europe’s record-setting spike for electricity prices -- and the transition amplified it.

The pain hitting Europe is an ominous sign of the types of shocks that could strike more of the globe. Even as solar and wind power become increasingly plentiful and cheap, many parts of the world will for decades still depend on natural gas and other fossil fuels as backups. And yet, investor and company interest in producing more of them is waning.

That’s a good recipe for volatility, Nikos Tsafos with the Center for Strategic and International Studies, wrote in a recent analysis.

“You’re definitely moving into a system that’s more vulnerable,” Tsafos, the center’s James R. Schlesinger chair for energy and geopolitics, said in an interview.

To be clear, the transition itself -- imperative for the planet -- didn’t cause the squeeze. But any big, complex system can become more fragile when it’s undergoing major change.

POWER DEMAND

All this is happening at a time when power consumption is projected to increase 60 per cent by 2050, according to BloombergNEF, as the world phases out fossil fuels and switches to cars, stoves and heating systems that run on electricity.

Continued economic and population growth will also drive consumption higher. And as the world moves even more into all things digital, it will mean that this heightened vulnerability comes at a time when people need reliable power more than ever.

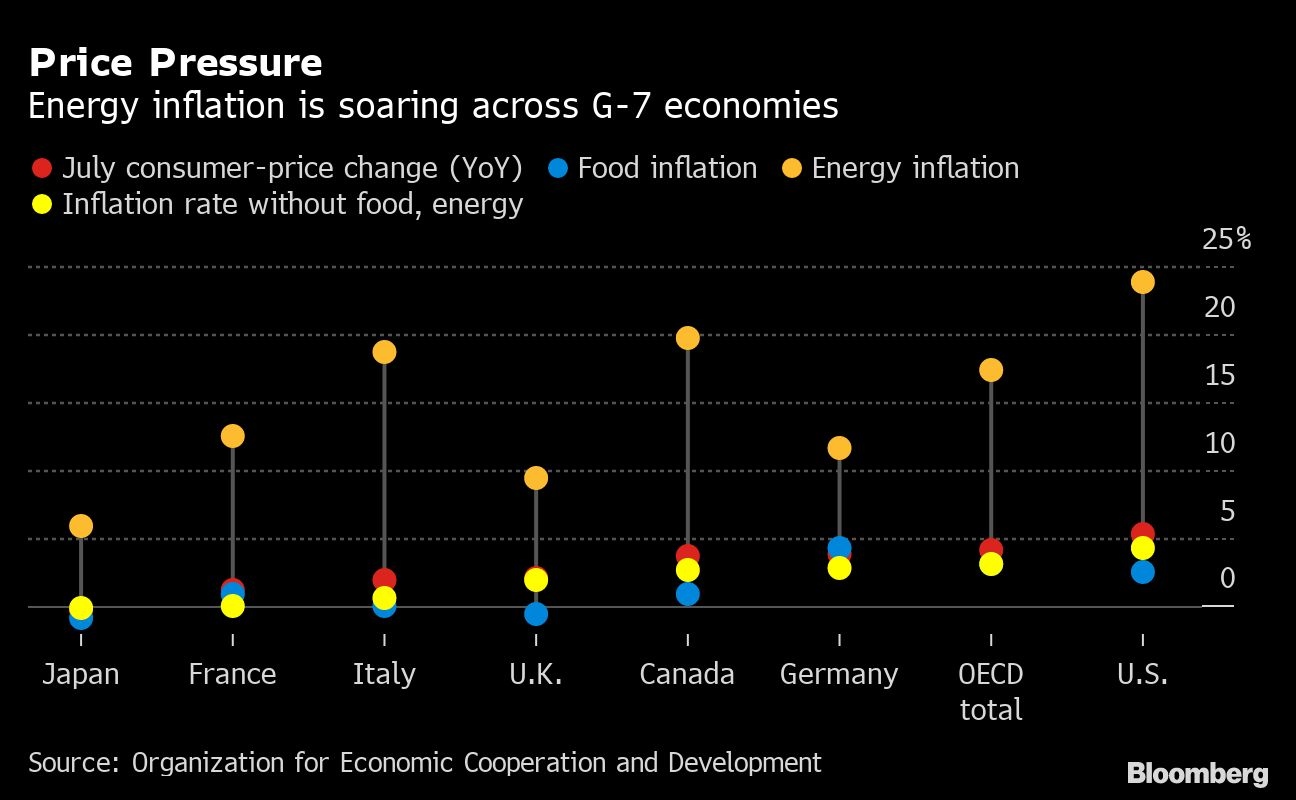

The surge in electricity demand combined with fuel-price volatility means the world could be in a for a rocky few decades. The consequences will likely range from periods of energy-driven inflation, exacerbating income inequalities, to the looming threat of power outages and lost economic growth and production.

GLOBAL FALLOUT

The planet’s energy systems are interconnected, so the crisis and its spillover are being felt across the world. The crunch has had knock-on effects across industries, obstructing silicon production, disrupting food supplies and snarling supply chains.

In the U.S., natural gas futures have already more than doubled this year, before the peak demand that comes with the winter cold. With 40 per cent of the country’s electricity now generated by burning gas, those higher prices will inevitably push up electricity and heating bills.

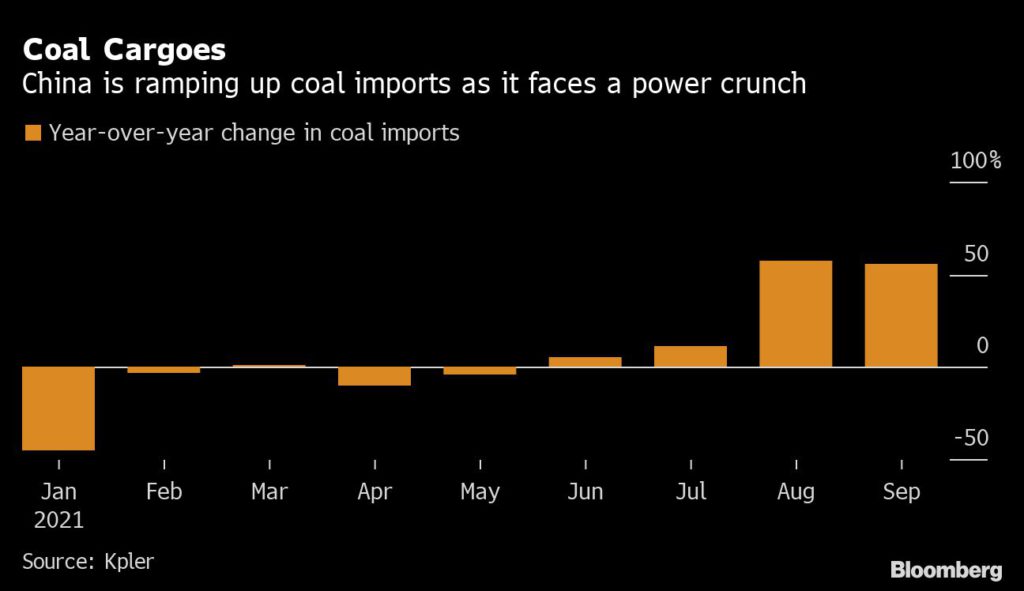

In China, even as the government pushes to ramp up renewable power, the industrial economy still relies heavily on fossil fuels: coal, gas and oil. And when its factories started humming again during the pandemic rebound, the country simply didn’t have enough fuel. Chinese manufacturing contracted in September for the first time in 19 months, suggesting that soaring energy costs have become the biggest shock to strike the economy since the beginning of the pandemic.

China’s government is now vowing to stabilize the situation by procuring more overseas coal and liquefied natural gas. That puts the nation in direct competition with Europe, threatening to starve the continent of fuel and worsen that crisis.

There will be an inevitable fight over what exports are available, leaving some developing countries such as India and Pakistan worried they can’t compete.

TIGHTER FUEL SUPPLIES

As major Western producers from BP Plc to Royal Dutch Shell Plc work to reduce emissions and America’s shale drillers take a step back from expansion, the finite amount of exportable supplies is growing tighter.

Jeff Currie, global head of commodities research at Goldman Sachs Group Inc., points to underinvestment in fossil fuels as a big part of the problem. Investors seeking the big returns that come from new businesses have been pouring money into alternative energy stocks rather than fossil fuel companies. Others are actively dumping coal and oil stocks, seeing them as a risk while the energy transition accelerates. And some fossil fuel companies have themselves started directing investments into the low-carbon future rather than focusing solely on their old role of finding, pumping and delivering more oil and gas.

“In many parts of the world, you’ve overbuilt wind, you’ve overbuilt solar,” Currie said in an interview on Bloomberg TV.

“The new economy is over-invested and the old economy is starved.”

Wind and solar power production have soared in the last decade. But both renewable sources are notoriously fickle -- available at some times and not at others. And electricity, unlike gas or coal, is difficult to store in meaningful quantities. That’s a problem, because on the electrical grid, supply and demand must be constantly, perfectly balanced. Throw that balance out of whack, and blackouts result.

So far, natural gas plants have served as the stable backup that wind and solar power need. That interdependence works fine, so long as gas prices aren’t going through the roof.

STORAGE SOLUTIONS

One of the biggest obstacles ahead will be storing power generated by intermittent wind and water sources. Solutions do exist, but it will be years before we have them at the scale on which they’re needed.

“The transition is both the challenge and the opportunity,” said Amy Myers Jaffe, managing director of the Climate Policy Lab at Tufts University.

Australia and California are plugging massive batteries into the grid to keep power supplies steady when the sun sets on solar plants. That deployment is just in nascent stages, and the batteries themselves are limited, usually supplying electricity for about four hours at a time. Many countries and companies have pinned their hopes on hydrogen, seeing it both as a way to store energy and as a fuel for transportation and industry.

Hydrogen can be split from water using machines called electrolyzers powered by renewable energy, whenever it’s abundant. The process produces no greenhouse gases. The hydrogen can then be burned in a turbine or fed through a fuel cell to generate electricity -- all without carbon emissions. And unlike oil, gas and coal, such “green hydrogen” can be produced most anywhere there’s water and strong sun or wind.

The first wave of green hydrogen plants is still in planning stages. Many of the potential users -- heavy industries and utility companies -- are still studying whether the solution will work for them. The point at which hydrogen could underpin our global energy system, if it arrives, is likely years away.

In the short term, a warm winter across the northern hemisphere would bring gas prices down and allow storage fields to fill back up. But the current price spike has served as a reminder that even as the world is trying to build a new energy system, it’s still reliant on the old one.

“It’s not just about capacity of the amount of power we can get onto the network, it’s about the flexibility and the ability to deliver that power at the right time,” said James Basden, founder and director of Zenobe Energy Ltd., which is building Europe’s biggest battery.

Bloomberg News | October 3, 2021 |

Dust-up in the coal trade. Stock Image.

Coal prices soared to their highest on record as China accelerated a global struggle for resources that has brought the dirtiest fossil fuel roaring back.

High-quality thermal coal loaded on ships at Newcastle port in Australia surged to $203.20 a ton, breaking the previous record set in July 2008. That’s the benchmark price for Asia, the world’s largest market for the fuel by far.

The rally comes during a global energy crunch that’s hitting China, the world’s biggest coal producer and consumer, especially hard. And as gas prices spike higher in Europe, there’s been a resurgence in demand for the fossil fuel that the continent’s policy makers have long been trying to phase out.

Still, there isn’t enough coal to go around. A German electricity producer closed one of its plants recently after it ran out of the fuel.

Earlier this week, Chinese Vice Premier Han Zheng ordered state-owned energy giants to secure fuel supplies for winter at any cost. China consumes and mines half the world’s coal, and it’s also the largest importer. The government told miners to keep digging even if they’ve exceeded their annual quota.

Prices for thermal coal tracked by IHS Markit and Argus have surged since late 2020 as demand rebounded from the depths of the pandemic and with substitute fuels like natural gas becoming more expensive. The emissions-heavy fuel is back in vogue just weeks before nations gather in Scotland for the COP26 summit on climate change.

Supply issues also boosted prices. China has struggled to raise output amid tighter safety controls following fatal accidents, while torrential rains, labor problems and transportation bottlenecks hampered exports from countries such as Indonesia, Australia, Colombia and South Africa, among others.

The Newcastle coal benchmark could average $190 a ton from October to December, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. said in a note in September.

The gains come as the world plans to shift away from the emissions-intensive fuel in favor of renewable sources that will help reach net-zero targets. Even China aims to start reducing domestic consumption by 2026, and President Xi Jinping pledged to stop building new coal-fired power plants abroad.

In the short term, demand in key nations is proving resilient. Thermal power generation in China was 14% higher in the year through August than in the previous two years. Demand in 2022 could be marginally higher than this year, potentially rising 1%, said Shirley Zhang, a coal analyst with Wood Mackenzie Ltd.

(By Dan Murtaugh, with assistance from Ann Koh and Stephen Stapczynski)

Global energy mess the first of many more shocks in the clean power era

In the throes of fundamental change, the world's energy system has become strikingly more fragile and easier to shock

Author of the article:

Bloomberg News

David R Baker, Stephen Stapczynski, Dan Murtaugh and Rachel Morison

Publishing date:Oct 05, 2021 •

The world is living through the first major energy crisis of the clean-power transition. It won’t be the last.

The shortages jolting natural gas and electricity markets from the U.K. to China are unfolding just as demand roars back from the pandemic. But the planet has faced volatile energy markets and supply squeezes for decades. What’s different now is that the richest economies are also undergoing one of the most ambitious overhauls of their power systems since the dawn of the electric age — with no easy way to store the energy generated from renewable sources.

The transition to cleaner energy is designed to make those systems more resilient, not less. But the actual switch will take decades, during which the world will still rely on fossil fuels even as major producers are now drastically shifting their output strategies.

“It is a cautionary message about how complex the energy transition is going to be,” said Daniel Yergin, one of the world’s foremost energy analysts and author of The New Map: Energy, Climate and the Clash of Nations.

In the throes of fundamental change, the world’s energy system has become strikingly more fragile and easier to shock.

Recipe for volatility

Take the turmoil in Europe. After a colder-than-normal winter depleted natural gas inventories, gas and electricity prices soared as demand from rebounding economies surged too fast for supplies to match. Something similar probably would have happened had COVID-19 struck 20 years ago.

But now, the U.K. and Europe rely on a very different mix of energy sources. Coal has been cut back drastically, replaced in many instances by cleaner-burning gas. But surging global demand this year has left gas supplies scarce. At the same time, two other sources of power — wind and water — have had unusually low output, thanks to unexpectedly slower wind speeds and low rainfall in areas including Norway.

In other words: A strained global gas market triggered Europe’s record-setting spike for electricity prices — and the transition amplified it.

The pain hitting Europe is an ominous sign of the types of shocks that could strike more of the globe. Even as solar and wind power become increasingly plentiful and cheap, many parts of the world will for decades still depend on natural gas and other fossil fuels as backups. And yet, investor and company interest in producing more of them is waning

That’s a good recipe for volatility, Nikos Tsafos with the Center for Strategic and International Studies, wrote in a recent analysis.

“You’re definitely moving into a system that’s more vulnerable,” Tsafos, the centre’s James R. Schlesinger chair for energy and geopolitics, said in an interview.

To be clear, the transition itself — imperative for the planet — didn’t cause the squeeze. But any big, complex system can become more fragile when it’s undergoing major change.

Power demand

All this is happening at a time when power consumption is projected to increase 60 per cent by 2050, according to BloombergNEF, as the world phases out fossil fuels and switches to cars, stoves and heating systems that run on electricity.

Continued economic and population growth will also drive consumption higher. And as the world moves even more into all things digital, it will mean that this heightened vulnerability comes at a time when people need reliable power more than ever.

The surge in electricity demand combined with fuel-price volatility means the world could be in a for a rocky few decades. The consequences will likely range from periods of energy-driven inflation, exacerbating income inequalities, to the looming threat of power outages and lost economic growth and production.

Global fallout

The planet’s energy systems are interconnected, so the crisis and its spillover are being felt across the world. The crunch has had knock-on effects across industries, obstructing silicon production, disrupting food supplies and snarling supply chains.

In the U.S., natural gas futures have already more than doubled this year, before the peak demand that comes with the winter cold. With 40 per cent of the country’s electricity now generated by burning gas, those higher prices will inevitably push up electricity and heating bills

In China, even as the government pushes to ramp up renewable power, the industrial economy still relies heavily on fossil fuels: coal, gas and oil. And when its factories started humming again during the pandemic rebound, the country simply didn’t have enough fuel. Chinese manufacturing contracted in September for the first time in 19 months, suggesting that soaring energy costs have become the biggest shock to strike the economy since the beginning of the pandemic.

China’s government is now vowing to stabilize the situation by procuring more overseas coal and liquefied natural gas. That puts the nation in direct competition with Europe, threatening to starve the continent of fuel and worsen that crisis.

There will be an inevitable fight over what exports are available, leaving some developing countries such as India and Pakistan worried they can’t compete.

Tighter fuel supplies

As major Western producers from BP Plc to Royal Dutch Shell Plc work to reduce emissions and America’s shale drillers take a step back from expansion, the finite amount of exportable supplies is growing tighter.

Jeff Currie, global head of commodities research at Goldman Sachs Group Inc., points to underinvestment in fossil fuels as a big part of the problem.

Investors seeking the big returns that come from new businesses have been pouring money into alternative energy stocks rather than fossil fuel companies. Others are actively dumping coal and oil stocks, seeing them as a risk while the energy transition accelerates. And some fossil fuel companies have themselves started directing investments into the low-carbon future rather than focusing solely on their old role of finding, pumping and delivering more oil and gas.

“In many parts of the world, you’ve overbuilt wind, you’ve overbuilt solar,” Currie said in an interview on Bloomberg TV.

The new economy is over-invested and the old economy is starvedJEFF CURRIE

“The new economy is over-invested and the old economy is starved.”

Wind and solar power production have soared in the last decade. But both renewable sources are notoriously fickle — available at some times and not at others. And electricity, unlike gas or coal, is difficult to store in meaningful quantities. That’s a problem, because on the electrical grid, supply and demand must be constantly, perfectly balanced. Throw that balance out of whack, and blackouts result.

So far, natural gas plants have served as the stable backup that wind and solar power need. That interdependence works fine, so long as gas prices aren’t going through the roof.

Storage solutions

One of the biggest obstacles ahead will be storing power generated by intermittent wind and water sources. Solutions do exist, but it will be years before we have them at the scale on which they’re needed.

“The transition is both the challenge and the opportunity,” said Amy Myers Jaffe, managing director of the Climate Policy Lab at Tufts University.

Australia and California are plugging massive batteries into the grid to keep power supplies steady when the sun sets on solar plants. That deployment is just in nascent stages, and the batteries themselves are limited, usually supplying electricity for about four hours at a time.

Many countries and companies have pinned their hopes on hydrogen, seeing it both as a way to store energy and as a fuel for transportation and industry.

Hydrogen can be split from water using machines called electrolyzers powered by renewable energy, whenever it’s abundant. The process produces no greenhouse gases. The hydrogen can then be burned in a turbine or fed through a fuel cell to generate electricity — all without carbon emissions. And unlike oil, gas and coal, such “green hydrogen” can be produced most anywhere there’s water and strong sun or wind.

European Industry Buckles Under a Worsening Energy Squeeze

Bloomberg News

Vanessa Dezem and William Wilkes

Publishing date: Oct 06, 2021 •

(Bloomberg) — European industry is being pushed closer to breaking point as the region’s energy crisis worsens by the day.

Power and gas prices are hitting fresh records almost daily, and some energy-intensive companies have temporarily shut operations because they’re becoming too expensive to run. As winter approaches and Europeans start to turn on their heaters, the squeeze will intensify, pushing more executives into tough decisions about keeping plants open.

Ammonia producer SKW Stickstoffwerke Piesteritz GmbH is among those that’s been forced into drastic steps. The German company, which burns through 640 gigawatt hours of natural gas each year, equivalent to about 50,000 households, said Tuesday it will cut production by 20% to offset rising gas prices.

“It doesn’t make sense to make ammonia at these price levels,” said Chief Executive Officer Petr Cingr. “A complete production stop looms if the government doesn’t act.”

On Wednesday, the European Union issued a fresh warning and said it will outline measures including tax cuts and state aid that governments can use to help.

“This price shock cannot be underestimated,” EU energy chief Kadri Simson said. “If left unchecked, it risks compromising Europe’s recovery.”

Those comments came a day after the U.K.’s Energy Intensive Users Group called on the government there to roll out emergency measures or face businesses shutting down this winter.

The crisis ripping through the region is the result of a supply crunch tangled up with a burst in demand after the Covid-19 pandemic. It threatens to put the brakes on the economic rebound by jacking up business costs and household energy bills, sending inflation to multi-year highs.

Many companies are trying to increase their energy efficiency, but any gains are being overwhelmed by the extent of the cost surge. The damage will worsen if the crisis evolves from a price shock to shortages, and more industries have to take the dramatic step of flicking the “off” switch.

There’s even a risk that governments intervene directly, as has happened in China. That could involve restrictions on industrial energy consumption to conserve dwindling supplies and keep homes heated over winter, especially at Christmas.

Front-month Dutch gas futures jumped as much as 22.4% on Wednesday after closing 20% higher on Tuesday. The U.K. equivalent benchmark jumped as much as 27.6%.

“It’s really scary,” said Carsten Rolle, head of the energy department at Germany’s BDI industry association. “The price rises make you dizzy.”

Last month, CF Industries Holding Inc., a major fertilizer maker, halted operations at two U.K. plants, citing high natural gas prices. Austria’s Borealis AG and Norwegian chemical firm Yara International ASA have also reduced output.

These measures will affect other industries, such as agriculture, adding to pressure on food prices. More widespread shutdowns would dent economic growth and put jobs at risk.

Options to alleviate the spikes seem to be limited. On the supply side, not much relief is expected from major natural gas producers, which have held back flows for their own domestic needs.

The longer the crisis drags on, the greater the chance of all-out supply shortages.

German giant BASF SE is already preparing for that, and says it’s secured long-term contracts with a range of gas providers to avoid getting hit by a crunch at any one supplier. The company’s Ludwigshafen facility, Europe’s largest chemical plant, has been designated “systemically relevant” by Germany’s grid operator, meaning its electricity supply wouldn’t be cut off in order to protect public supplies.

The impact of record gas, electricity and carbon prices has been greater on small and medium industrial producers, which have fewer financial protection options and are more exposed to volatility.

Already hurt by coronavirus lockdowns, many of Germany’s smaller firms decided against securing long-term energy supplies earlier this year and can’t afford to catch up now as gas prices are so high, according to Andreas Loeschel, professor of resource economics at Ruhr-University Bochum.

“So much depends on the the demand side of the equation,” he said, referring to the potential for a colder-than-expected winter. “A number of unlikely events are building up to cause a situation we’ve never seen before.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

Bloomberg.com

The Energy Transition Will Take Decades Not Years

- With natural gas, coal, and oil prices all soaring this summer, it is clear that a successful energy transition will take decades not years

- Some energy transition proponents may have confused Covid energy demand destruction with a change in consumer behavior

- The truth is that an energy transition can only occur when clean energy can be provided both cheaply and reliably

This year’s global demand for all three fossil fuels has sent a message to overly enthusiastic proponents of the energy transition - hold your horses.

Those who predicted last year the demise of oil, gas, and coal after the pandemic and those who said that peak oil demand was already behind us because lasting changes in consumer behavior would reduce the use of crude are now facing reality.

Global oil demand is just a few months away from reaching pre-pandemic levels, while natural gas and coal demand have already exceeded the 2019 volumes.

Sure, international airline travel is still struggling because of COVID-related travel restrictions in place in many countries. But economies are bouncing back, industries are growing, and the world needs a lot of energy, once again.

Fossil Fuels Support Economic Growth

And fossil fuels continue to supply most of that energy and will do so for years to come. Last year’s slump in fossil fuel consumption is being erased, and those who expected oil, gas, and coal demand to never return to pre-COVID levels now know they were wrong.

Also wrong were all those who hoped the ‘build back greener’ policies that governments pledged last year would suddenly lead to solar, wind, biofuels, sustainable aviation fuels, and hydrogen displacing fossil fuel-generated energy overnight.

Economies are recovering post-COVID, and consumer habits haven’t changed all that much: consumers still want a warm home, power, the latest tech gadgets, and to be able to freely travel and spend money.

Apart from a share of renewables for power generation, solar and wind, for example, are not really providing the energy and all the stuff consumers buy. Fossil fuels do. And they will continue to do so for at least another decade until the energy transition - including in industries other than power generation - accelerates.

The share of renewable energy sources in electricity generation continues to rise, but renewables are incapable of meeting the rebounding power demand, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said in July.

The IEA also says that if the world were to meet a net-zero target in 2050, it should stop investing in new oil, gas, and coal supply now.

Yet, these days, both the most developed economies in Europe and the fastest-growing developing economies in Asia - China and India - are experiencing first-hand what undersupplied coal and gas markets mean: very high prices of energy commodities and power supply, and industries halting factories because of shortage of electricity or gas.

Coal And Gas Demand Back Above Pre-Covid Levels

The post-COVID economic recovery drove demand for oil, coal, and gas, with coal and gas consumption already exceeding pre-pandemic levels. As a result, the record slump in global emissions from 2020 is also being erased, posing another conundrum to the global fight against climate change.

On average, coal demand declined by 4 percent last year - the steepest drop since World War II - but it was already back to pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2020, the IEA says.

“Coal use in the fourth quarter was 3.5% higher than in the same period in 2019, contributing to a resurgence in global CO2 emissions,” Carlos Fernández Alvarez, Senior Energy Analyst at the IEA, wrote in a commentary in March.

This year, coal demand is rebounding strongly in 2021, driven by the power sector, the agency said in its Global Energy Review 2021 in April. Natural gas demand is also bouncing back and is expected to erase the 2020 loss and push demand 1.3 percent above 2019 levels, as per IEA estimates in the same review.

Oil Demand Set To Reach 2019 Levels Within A Few Months Oil demand is also on track to soon reach 2019 levels and exceed them. Many analysts and oil companies see global oil demand returning to the pre-crisis levels of 2019 as early as the start of next year, if not earlier, by the end of 2021. According to OPEC’s latest estimate, global oil demand in 2022 will average 100.8 million bpd and exceed pre-COVID levels.

Related: Gas Prices In Europe Are Now The Equivalent Of $205 Oil

The current gas, coal, and power crisis in Europe and Asia is also set to accelerate oil demand recovery in the winter if gas-to-oil switching becomes more widespread.

By early 2022, demand for all fossil fuels is expected to have reached or exceeded pre-pandemic levels, highlighting the challenges of the energy transition to secure reliable - and preferably affordable - energy for the world.

“The energy transition and decarbonisation are decade-long strategies and do not happen overnight,” Cuneyt Kazokoglu, head of oil demand analysis at consultancy FGE, told Reuters.

Last year’s slump in fossil fuel demand had nothing to do with the energy transition: it had everything to do with the lockdowns and economic decline, Kazokoglu said.

A rushed transition without considering the still enormous role that fossil fuels play in the economy and consumers’ lifestyle risks exposing the global energy market to supply crunches and price spikes.

“Prices for fossil fuels will remain volatile, perhaps more so than today since the risk of a supply-demand imbalance is greater in a market that is shrinking where the case for further investment is weak, which could produce short-term rallies,” Nikos Tsafos, the James R. Schlesinger Chair for Energy and Geopolitics with at Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), wrote in a commentary last month.

The price of commodities critical for the energy transition - such as the key metals lithium, cobalt, nickel, or copper - are also prone to volatility, Tsafos notes.

The energy transition will not be smooth sailing and will take decades. In the meantime, fossil fuels will continue to support the global economy and the security of the energy supply.

Even the IEA, while saying that well-managed energy transitions would be the solution - not the problem - in the current gas and power crises, acknowledged that “The links between electricity and gas markets are not going to go away anytime soon. Gas remains an important tool for balancing electricity markets in many regions today.”

By Tsvetana Paraskova for Oilprice.com