World's largest whales eat more than previously thought, amplifying their role as global ecosystem engineers

New research co-authored by Nicholas Pyenson, curator of fossil marine mammals at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, shows evidence that the world's largest whales have been sold short. The study, published today in the journal Nature, finds that gigantic baleen whales—such as blue, fin and humpback whales—eat an average of three times more food each year than scientists have previously estimated. By underestimating how much these whales eat, scientists may also have been previously underestimating the importance of these undersea giants to ocean health and productivity.

Since whales eat more than previously thought, they also poop more, and whale poop is a crucial source of nutrients in the open ocean. By scooping up food and pumping out excrement, whales help keep key nutrients suspended close to the surface where they can power blooms of the carbon-absorbing phytoplankton that form the base of ocean food-webs. Without whales, those nutrients more readily sink to the seafloor, which can limit productivity in certain parts of the ocean and may in turn limit the capacity of ocean ecosystems to absorb planet-warming carbon dioxide.

The findings come at a pivotal moment as the planet faces the interconnected crises of global climate change and biodiversity loss. As the planet warms, the oceans absorb more heat and become more acidic, threatening the survival of food sources that whales need. Many species of baleen whales also have not recovered from industrial whaling during the 20th century, remaining at a small fraction of their pre-whaling population sizes.

"Our results say that if we restore whale populations to pre-whaling levels seen at the beginning of the 20th century, we'll restore a huge amount of lost function to ocean ecosystems," Pyenson said. "It may take a few decades to see the benefit, but it's the clearest read yet about the massive role of large whales on our planet."

Surprisingly, some basic biological questions remain unanswered when it comes to the world's biggest whales. Marine ecologist and Stanford University postdoctoral fellow Matthew Savoca, one of Pyenson's collaborators and lead author of the study, found himself confronted by one of these remaining mysteries: how much the massive filter-feeding baleen whales ate each day.

Savoca said the best estimates he encountered from past research were guesses informed by few actual measurements from the species in question. To crack the conundrum of just how much food 30- to 100-foot whales eat, Savoca, Pyenson and a team of scientists used data from 321 tagged whales spanning seven species living in the Atlantic, Pacific and Southern Oceans collected between 2010 and 2019.

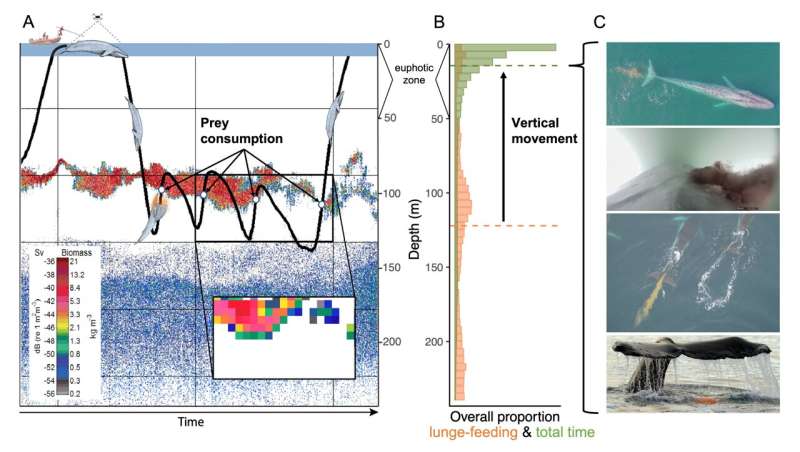

Savoca said each of these tags, suction-cupped to a whale's back, is like a miniature smartphone—complete with a camera, microphone, GPS and an accelerometer that tracks movement. The tags track the whales' movements in three-dimensional space, allowing the team to look for telltale patterns to figure out how often the animals were engaged in feeding behaviors.

The data set also included drone photographs of 105 whales from the seven species that were used to measure their respective lengths. Each animal's length could then be used to create accurate estimates of its body mass and the volume of water it filtered with each mouthful. Finally, members of the team involved in this near-decade-long data collection effort used small boats equipped with echo-sounders to race to sites where whales were feeding. The echo-sounders use sound waves to detect and measure the size and density of swarms of krill and other prey species. This step was crucial empirical grounding for the team's estimates of just how much food the whales might be consuming.

By braiding these three lines of evidence together—how often whales were feeding, how much prey they could potentially consume while feeding and how much prey was available—the researchers could generate the most accurate estimates to date of how much these gargantuan mammals eat each day and, by extension, each year.

For example, the study found an adult eastern North Pacific blue whale likely consumes 16 metric tons of krill per day during its foraging season, while a North Atlantic right whale eats about 5 metric tons of small zooplankton daily and a bowhead whale puts down roughly 6 metric tons of small zooplankton per day.

To quantify what these new estimates mean in the context of the larger ecosystem, a 2008 study estimated that all of the whales in what is known as the California Current Ecosystem, which stretches from British Columbia to Mexico, required about 2 million metric tons of fish, krill, zooplankton and squid each year. The new results suggest that the blue, fin and humpback whale populations living in the California Current Ecosystem each require more than 2 million tons of food annually.

To demonstrate how more prey consumption by whales increases their capacity to recycle key nutrients that might otherwise sink to the seafloor, the researchers also calculated the amount of iron all this extra whale feeding would recirculate in the form of feces. In many parts of the ocean, dissolved iron is a limiting nutrient, meaning that there might be plenty of other key nutrients such as nitrogen or phosphorus in the water, but a lack of iron prevents potential phytoplankton blooms. Because whales eat so much, they end up ingesting and excreting substantial amounts of iron. Prior research found whale poop has around 10 million times the amount of iron found in Antarctic seawater, and because whales breathe air they tend to defecate near the surface—just where phytoplankton need nutrients to help power photosynthesis. Using past measurements of the average concentrations of iron in whale poop, the researchers calculated that whales in the Southern Ocean recycle roughly 1,200 metric tons of iron every year.

These surprising findings led researchers to investigate what their results might tell them about the marine ecosystem before industrial whaling slaughtered 2 to 3 million whales over the course of the 20th century. Based on whaling industry records of animals killed in the waters surrounding Antarctica in the Southern Ocean, the researchers used existing estimates of how many whales used to live in the region combined with their new results to estimate how much those animals likely ate.

According to the analysis, minke, humpback, fin and blue whales in the Southern Ocean consumed some 430 million metric tons of krill annually at the beginning of the 1900s. That total is double the amount of krill in the entire Southern Ocean today and is more than twice the total global catch from all human wild-capture fisheries combined. In terms of the whales' role as nutrient recyclers, the researchers calculate that whale populations, before losses from 20th-century whaling, produced a prodigious flow of excreta containing 12,000 metric tons of iron, 10 times the amount whales currently recycle in the Southern Ocean.

These calculations suggest that when there were a lot more whales chowing down on krill, there must have been a lot more krill for them to eat. Savoca said that the decline of krill numbers following the loss of so many of their biggest predators is known to researchers as the krill paradox and that the decline in krill populations is most pronounced in areas where whaling was especially intense, such as the Scotia Sea between the Southern Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean southeast of South America.

"This decline makes no sense until you consider that whales are acting as mobile krill processing plants," Savoca said. "These are animals the size of a Boeing 737, eating and pooping far from land in a system that is iron-limited in many places. These whales were seeding productivity out in the open Southern Ocean and there was very little to recycle this fertilizer once whales were gone."

The paper posits that restoring whale populations could also restore lost marine productivity and, as a result, boost the amount of carbon dioxide sucked up by the phytoplankton—which are eaten by krill. The team estimates that the nutrient cycling services provided by pre-whaling populations at the start of the 20th century might fuel a roughly 11% increase in marine productivity in the Southern Ocean and a drawdown of at least 215 million metric tons of carbon, absorbed and stored in ocean ecosystems and organisms in the process of rebuilding. It is also possible these carbon reduction benefits would accrue year over year.

"Our results suggest the contribution of whales to global productivity and carbon removal was probably on par with the forest ecosystems of entire continents, in terms of scale," Pyenson said. "That system is still there, and helping whales recover could restore lost ecosystem functioning and provide a natural climate solution."

Pyenson said he, Savoca and others are pondering what the impact of whales might be if the team had been less conservative with their estimates, as well as a potential line of research comparing the relatively recent losses of large mammals in the sea to those lost on land, such as the American bison. Though based at Stanford, Savoca will continue his work this fall at the Smithsonian collecting samples from its extensive baleen whale collections.Study suggests climate change could prevent recovery of southern right whales

More information: Matthew Savoca, Baleen whale prey consumption based on high-resolution foraging measurements, Nature (2021). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-03991-5. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03991-5

Journal information: Nature

Provided by Smithsonian