For FBI legend J. Edgar Hoover, Christian nationalism was the gospel truth, argues new book

In 'The Gospel of J. Edgar Hoover,' Stanford professor Lerone Martin details how the longtime FBI director shaped the belief in America as a Christian nation.

(RNS) — Lerone Martin’s new book began with a cup of coffee that led him to sue the FBI.

While working on a book about religious broadcasters, a colleague suggested over coffee that Martin, a religion scholar, research the FBI to see if they had any related files. At the time, the colleague, scholar William J. Maxwell, author of “F.B. EYES,” had been studying the FBI’s surveillance of Black writers. Perhaps the FBI had been keeping an eye on religious broadcasters as well.

Martin, then living in St. Louis, began filing Freedom of Information requests. Around the same time, he was also hearing from local pastors in St Louis who had been contacted by the FBI in the wake of the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson. The FBI, they told Martin, wanted to know what the pastors were going to do to calm protests in that city.

“That got me thinking,” said Martin. “This is not a surveillance story. This is a story of partnership.”

Martin began thinking about the kinds of pastors the FBI might want to partner with. Chief among them was the late evangelist Billy Graham, known for his crusades for Jesus and against communism and liberals.

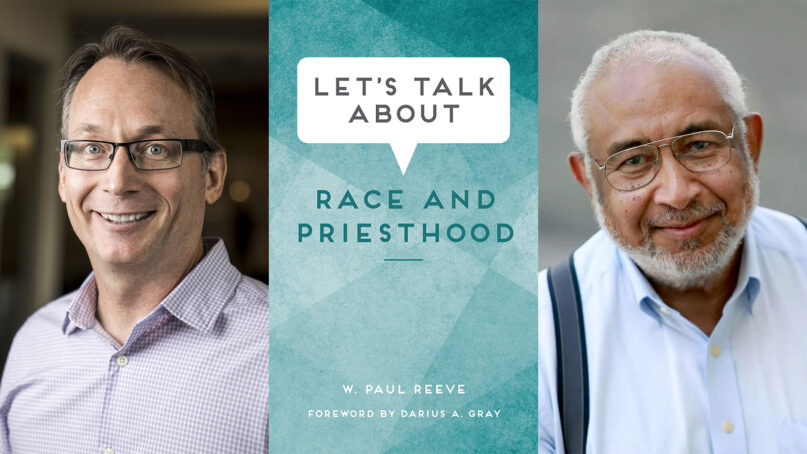

Lerone Martin. Photo by Andrew Brodhead/Stanford University

When Graham died in 2018, Martin asked for his FBI file. The Department of Justice said no. So, Martin sued in federal court and three years later settled with the FBI and got the files. He also obtained files on other Christian leaders and organizations, most notably more than a thousand pages of documents outlining the relationship between longtime FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and the editors of Christianity Today, the flagship publication of Graham’s evangelical movement.

What Martin, now an associate professor of religion at Stanford, found in those files was this: Hoover was perhaps the most influential Christian leader in America during his tenure in office, promoting a gospel of America as a Christian nation and labeling anyone who threatened the power of white Christian men as communists and a threat to God’s will.

“Hoover saw his politics as nothing more than an extension of his faith,” said Martin, author of “The Gospel of J. Edgar Hoover: How the FBI Aided and Abetted the Rise of White Christian Nationalism.“ “And because America is a Christian nation, the FBI is charged with defending and perpetuating that ideal.”

RELATED: Old-school Christian nationalism’s avatar of racism, antisemitism and conspiracies

Unlike early Christian nationalists, like Father Charles Coughlin — a star of early broadcast radio — or Gerald L.K. Smith, longtime editor of “The Cross and the Flag,” Hoover had the institutional power and discipline to make his beliefs stick. And he had a gift for convincing conservative Christian leaders to join his crusade.

When the Nation magazine ran a series of articles critical of the FBI and Hoover, legendary Christianity Today editor Carl Henry rode to his aid, offering to run one of Hoover’s essays in the magazine. When the essay arrived, Henry was effusive in his praise.

In his book, Martin documents how Hoover saw anyone who upset the status quo and pushed for goals like “love, justice, and the brotherhood of man” or “personal freedom” as part of an atheistic communist plot. He used the power of his office to investigate those who opposed him, including religious leaders like the National Council of Churches and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

“The Gospel of J. Edgar Hoover: How the FBI Aided and Abetted the Rise of White Christian Nationalism” by Lerone Martin. Courtesy image

He turned his office into a bully pulpit, writing essays for major Christian publications, saying that all the nation’s problems — including issues of race — could be solved if only everyone gave their hearts to Jesus. The FBI then reprinted those essays, adding an FBI seal as if they reflected official government policies, and shared them with churches, Sunday schools and almost anyone who wanted them.

Some preachers even preached them word for word on Sundays, Martin recounts, complete with Hoover’s warnings of disaster if America strayed from its spiritual roots and the Marxists took over.

“We are today threatened by twin menaces,” he wrote in a 1961 essay for Christianity Today. “Materialism has fathered both crime and communism. The criminal statistics for the year just past attest to the steady growth of the one evil. The progress of the other — and the intensity of the struggle in which we are engaged with it — does not yield to such forthright measure.”

Many evangelical leaders were eager to join Hoover’s crusade against communism and liberals. They also saw the advantages of having Hoover as an ally, said Martin in an interview.

“What better way in the midst of a cold war to authenticate your organization than to have the approval of the FBI — the organization that knows all and sees all?” said Martin.

Evangelicals embraced Hoover even though he shared few of their theological convictions. He did not believe in being “born again,” said Martin, and never had the kind of conversion experience that is so essential to evangelical life. He also did not share evangelical prejudice against Catholics, which was common in the middle of the 20th century. Instead, Martin writes, he saw Catholics as essential partners.

“I am a Protestant,” he said in a 1939 address to a Catholic gathering in Washington, D.C., that is recounted in Martin’s book. “And as a Protestant, I say sincerely and from experience, that the Catholic Church is the greatest protective influence in our nation today.”

Martin writes that Hoover was a particular admirer of the Society of Jesuits and recruited Jesuit priests to train FBI agents to be spiritual warriors. The FBI held yearly retreats for agents at a Jesuit retreat house in Annapolis led by his friend, the Rev. Robert S. Lloyd, and donated a chalice engraved with “FBI” to Lloyd for use during Mass.

The agency also held an annual Mass and Communion breakfast for Catholic agents and an interdenominational vespers service for Protestant agents to counter rumors the FBI had been taken over by Catholics. At both, only White Christian agents were welcomed, Martin writes. Agents of color never received invitations.

J. Edgar Hoover, left, fingerprints Vice President John N. Garner, circa 1939. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress/Creative Commons

In an interview, Martin said Hoover was a true Christian nationalist, who believed he was working for God — not the Constitution or the American people. He saw enforcing the law as a spiritual battleground, said Martin, a view he developed as a teenage Sunday school teacher.

“He saw Sunday school as spiritual formation — and believed the Bible teaches you how to live your life in a moral way,” he said. “And if you follow the teachings of God, you will be a great American citizen. And then the reverse of that is — if you’re a criminal, that means that you didn’t get the spiritual teachings as a child. And if you did get them and are a criminal, you’ve just decided to reject them.”

Hoover’s commitment to law and order above all and his views of America as a white Christian nation led him to reject Martin Luther King Jr. and other leaders of the civil rights movement. Martin, who also directs the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford, said Hoover dismissed civil rights legislation as misguided and called King and other civil rights leaders “extremists.”

“Hoover’s gospel was focused on the individual soul,” Martin writes. “The best way to fix America’s race problem was not violence, protest, or legislation. Rather, individual and group piety was the best way for Black Americans to earn white respect and the eventual prize of equality.”

Any other approach, Hoover believed, was simply the work of communists.

Hoover remained influential for decades, said Martin, in part because he was a master at mythmaking. During his tenure, the FBI and its agents were cultural heroes, stars of “This Is Your FBI,” a popular radio program; television shows like “The Untouchables”; and a long list of movies. In the popular imagination, the FBI was America’s protector — which, combined with his endorsements of Christian America, turned Hoover into one of the most well-respected people in the country.

Martin said Hoover’s views — and his strategies — still shape American politics. Especially his habit of labeling all his enemies as socialists or Marxists. Doing that, Martin said, allowed Hoover to dismiss any criticism of American culture.

“Today we see people using ‘socialist’ the same way,” he said. “It’s a tactic where you don’t have to actually engage opposing ideas, you can just dismiss them while using that label.”

RELATED: How big Christian nationalism has come courting in North Idaho

(This story was was reported with support from the Stiefel Freethought Foundation.)