INTERVIEWCOMPLETE TEXT OF KAFKA’S DIARIES IN ENGLISH FOR THE 1ST TIME

Kafka uncensored: A new version of the writer’s diaries adds back the sordid details

When the ‘Metamorphosis’ author died his friend Max Brod published his journals – cutting the parts he thought too personal. Now they’re complete thanks to translator Ross Benjamin

21 April 2023

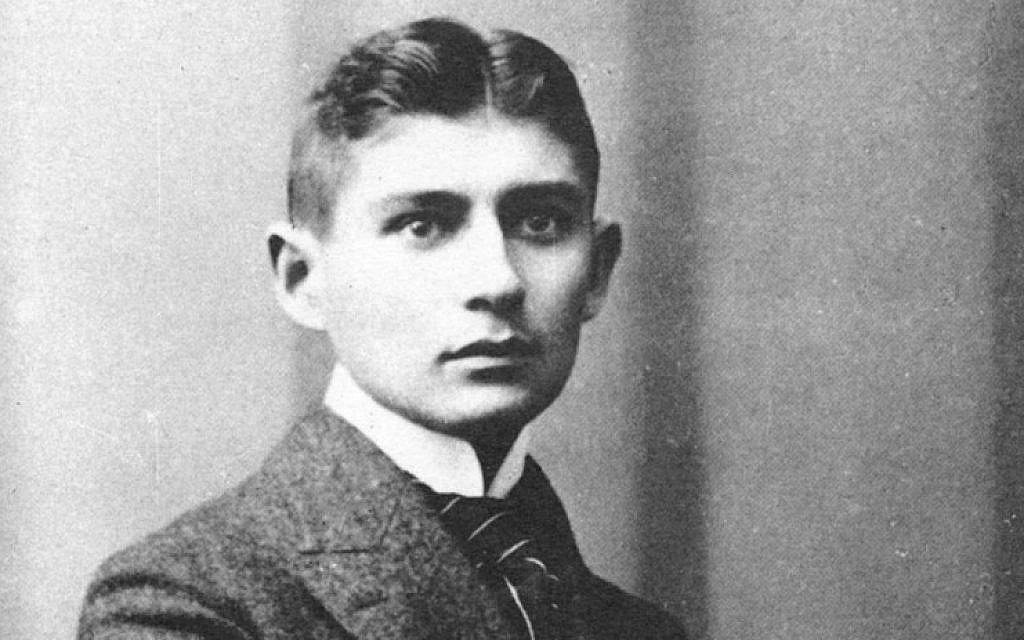

Franz Kafka in 1906. (Public domain)

In 1915, Franz Kafka read two draft chapters of his novel in progress, “The Trial,” to his close friend and fellow writer, Max Brod. “The Trial” remained uncompleted when Kafka died from tuberculosis in June 1924 at the age of 40.

Prior to his death, Kafka — who was born into a German-speaking Jewish family in what was then the Bohemian capital of Prague — left strict written instructions for Brod to burn all of his literary manuscripts, with the exception of three or four short stories. Brod betrayed his friend’s last wishes.

A committed Zionist, Brod fled the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1939, emigrated to Mandatory Palestine, and died in Tel Aviv in 1968. As Kafka’s sole literary executor, Brod edited and prepared posthumous editions of Kafka’s unpublished novels: “The Trial” came out in 1925, followed by “The Castle” in 1926, and “The Missing Person,” which Brod retitled “Amerika,” in 1927.

Brod also published two volumes of Kafka’s diaries, in English, in 1948-49. The first volume was translated by Joseph Kresh and the second by Martin Greenberg in cooperation with Hannah Arendt, who was then an editor at Schocken Books in New York. In the postscript to volume one of the diaries in 1948, Brod claimed the diaries were as complete as it was possible to make them. “A few passages, apparently meaningless because of their fragmentary nature are omitted,” Brod wrote.

Ross Benjamin, an American translator of German-language literature, now claims Brod was being economical with the truth.

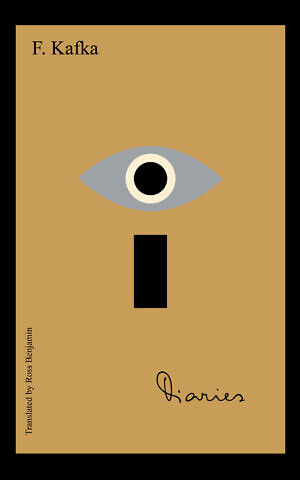

“Besides omitting or altering the names of and details about people still living at the time of the [diaries] publication, Brod manipulated the diaries in several places that presumably seemed to him to reflect unfavorably on himself or Kafka,” Benjamin writes in the preface to “The Diaries of Franz Kafka,” which published in early January.

Ross Benjamin, translator of a new version of ‘The Diaries of Franz Kafka.’ (Courtesy/ David Schloss)

The book took Benjamin eight years to translate from the original German and offers English-speaking readers the complete text of Kafka’s diaries for the first time. Written between 1909 and 1923, the diaries contain daily events, reflections and observations, literary sketches, letters, reviews, accounts of dreams, outlines for future planned creative works, descriptions of people with whom Kafka crossed paths, and all but finished prose pieces. In 1913, Kafka wrote in one diary entry: “I am made of literature. I am nothing else and cannot be anything else.”

Benjamin’s previous translations include Daniel Kehlmann’s “Tyll” and “You Should Have Left,” and Joseph Roth’s “Job.” In 2010, Benjamin was awarded the Helen and Kurt Wolff Translator’s Prize for his translation of Michael Maar’s “Speak, Nabokov.” Benjamin’s writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Times Literary Supplement, Bookforum, The Nation, and other publications.

The Times of Israel caught up with Benjamin via Zoom from his home in Nyack, New York, to speak about his new translation of Kafka’s diaries and the insights they give us into Kafka’s life and work. The conversation has been edited for clarity.

The Times of Israel: In the preface to these diaries, you are very critical of Kafka’s friend and literary executor, Max Brod. What kind of things did Brod censor from Kafka’s diaries that were published in English in 1948-49?

Ross Benjamin: Brod deleted whole huge chunks of text that he thought were too personal. He also deleted literary texts that Kafka had drafted in the diaries, which Brod slapped a title on and then published as fiction elsewhere. Brod authorized himself to take liberties with Kafka’s texts and made the decision that since he was the one who [really] knew Kafka, he knew what should be part of Kafka’s literary legacy and what should be shielded from public view.

‘The Diaries of Franz Kafka,’ translated by Ross Benjamin. (Courtesy: Schocken Books)

Did Brod censor and edit the diaries in parts where Kafka wrote about Brod?

Sometimes Brod kept in passages where Kafka wrote about him critically. For example, Kafka wrote at one point in the diaries: “Me and Max must be fundamentally different.” Brod did not cut that. But he cut other entries which he was more sensitive about. An entry, for instance, where Kafka described how Brod came back from a reading he did in Berlin in December 1911 and how a critic, Franz Werfel, had written something disparaging about Brod afterward in a review. Kafka’s diary documented how Brod had those disparaging remarks removed, and how Brod then had the review reprinted (minus the criticism) in a Prague daily newspaper, the Prager Tagblatt. Brod, however, cut all that detail in the diaries.

Brod spent many decades championing Kafka’s prose to a global audience. But he also mythologized Kafka’s life and biography. Can you talk about this?

Brod idealized Kafka as a writer and once said that “the proper category for understanding Kafka is the category of sainthood, not the category of literature.” Personally, I think it is the category of literature. I don’t get the impression that Brod was branding or marketing Kafka as this saint figure. I think that’s how he genuinely saw Kafka, at least after his death.

Did Brod’s editorial decisions alter Kafka’s prose significantly, specifically, in Kafka’s three novels that were published posthumously?

Brod inserted standard punctuation, and he also fixed the syntax where it was muddled. Kafka, after all, wrote hastily. Brod also rearranged the texts of those novels and decided the chronology of the chapters, which were just part of a whole lot of material that Kafka left behind. For example, Brod left out certain fragments that he could not piece together from “The Trial.” But other versions of “The Trial” have since appeared [in print] that kept in those same rough edges of Kafka’s prose in the novel that Brod had ironed out.

You describe Kafka’s diaries as “a laboratory for his literary production.” What do you mean by this?

In many instances in the diaries, Kafka is actually writing as a fictional narrator rather than as a diarist. Every time Kafka was writing he was potentially crafting literature.

Your new translation of the diaries, it seems, brings potential new revelations about Kafka’s sexuality. You mention, for instance, that Brod deleted a line where Kafka describes how a fellow male train passenger’s “sizeable member makes a large bulge in his pants.” Elsewhere, there is a diary entry where Kafka goes to a nudist sanatorium and sees two Swedish boys. In Brod’s version, it simply reads: “Two handsome Swedish boys with long legs.” In your version of that same diary entry, however, it reads quite differently: “2 beautiful Swedish boys with long legs, which are so formed and taut that one could really only run one’s tongue along them.”

The passages that I have included, which were cut by Brod, show clear moments of homoerotic desire from Kafka, which was less well known before [in English translations of the diaries] so I believe they add to our understanding of Kafka’s sexuality. Kafka was always a seeker and explorer in all areas of his life. It kind of makes sense to me that Kafka would explore other aspects of his sexuality in his writing.

Drawings by Franz Kafka from the literary estate of Max Brod. (National Library of Israel)

Brod and Kafka visited brothels together in Prague, Milan, Leipzig, and Paris. Some of those visits are documented in Brod’s original English version of Kafka’s diaries. Did Brod censor any of those details?

Kafka’s visits to brothels aren’t completely censored. They were, however, sanitized in Brod’s English translation. Take, for example, Kafka’s diary entry regarding a visit to a Milan brothel [in 1911]. Kafka wrote: “The girl by the door, whose scowling face is Spanish, who’s putting her hand on her hips in Spanish and who stretches in a bodice-like dress of prophylactic silk. Hair runs thickly from her navel to her private parts.” In Brod’s version of the diary, he cut the last line of this passage. Why, though? It’s hard to say. Did he see it as too crudely carnal and lascivious?

What do these diaries tell us about Kafka’s relationship with women?

Kafka had a very fraught and tortured relationship with women in general. His description of women in [these diaries] often seems to be describing what seems like disgust, but attraction/repulsion, too. Kafka’s first diary entry documenting his impression of Felice Bauer [whom he later got engaged to twice], for example, reads like he had met somebody who he found pretty ugly, uninteresting, and dull. He describes her as having almost “a broken nose and stiff charmless hair.” But then Kafka wrote Felice Bauer letters afterward describing his supposed infatuation with her. Kafka had trouble with what we would today call heteronormative monogamy.

Kafka was engaged three times to two different women, but he never actually married. He wrote obsessively in his diaries about his status as a bachelor. It seemed to cause him a great deal of anxiety.

Yes. The word bachelor comes up hundreds of times throughout the diaries. There is a lot that could be read into that question too, in terms of Kafka’s sexuality. One of the ways Kafka framed this moral conflict was with reference to the French author, Gustave Flaubert, who justified being a bachelor in order to fully devote himself to his art and literature. Kafka bought into that myth. But that inner conflict about bachelorhood versus marriage and having a family is constant in Kafka’s diaries because he never resolved it.

You also suggest that Kafka’s inner conflicts and anxieties became the fundamental source of his creative work, too.

Absolutely. Kafka was constantly coming up with new metaphors, images, and allegories to think about these inner [psychological] conflicts, which caused him a great deal of stress. Kafka suffered a lot mentally, but he used his creativity to transform that suffering into literary expression.

An original manuscript written in Hebrew by Franz Kafka is displayed at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem, May 31, 2021. (Menahem Kahana/AFP)

In the preface to these diaries, you explore how Brod covered up “occasional lapses in Kafka’s generally positive and open-minded attitude towards Eastern European Jews.” You cite, for example, a traveling Yiddish theater troupe from Lemberg (Lviv) that came to Prague several times in 1911 and 1912, that Kafka saw over 20 times and wrote about those performances in the diaries. Kafka also befriended one member of the group, Polish actor Jizchak Löwy. What did Brod censor in these passages?

It might first be worth mentioning that Kafka’s father embodied a snobbish Jewish attitude that was typical of many Jews from Western Europe towards Eastern European Jews. Kafka wrote about this in his diaries and described how his father made contemptuous comments about the fact that Kafka befriended Löwy. His father even compared Löwy to an animal or an insect. In German, the phrase for looking down on Eastern European Jews was Ostjuden [Eastern Jews], a pejorative term. Although in the diaries Kafka used the term “Eastern Jews.”

But to return specifically to the diary entry you ask about, Kafka’s overall interaction with this Eastern European Yiddish theater group was one of great excitement. Kafka was at the theater with Jizchak Löwy, [who] mentioned his gonorrhea. Brod cut that. Then Kafka wrote: “I leaned over my head, touched his, and I became afraid due to the possibility of lice.” It seems that Kafka was registering his fear of the hygiene of this Eastern European Jew. Kafka probably recognized his own anxieties as typical of Western Jewish prejudices. Now, in my view, it’s much more interesting to see Kafka grapple with this issue rather than have it cleaned up [as Brod did], which would [suggest] that Kafka had uniformly open-minded and positive attitudes about his Jewish friends from Eastern Europe.

Can you speak about Kafka’s rediscovery of his Jewish identity — particularly his keen interest in Yiddish culture and Zionism — which came late in his life?

Kafka became really engaged with his own Jewishness during the time these diaries were written. But Kafka’s interest in Zionism, like his interest in many contemporary [political, cultural, and philosophical] movements, was somewhat distant and skeptical. He began to learn Hebrew late in life, with a possible view to move to Palestine. But there is a famous passage in the diaries where Kafka wrote, “What do I have in common with the Jews? I don’t even have anything in common with myself.”

How would you sum up Kafka’s character? There is a perception of him in the literary world as a kind of nervous wreck or an anxious introvert. Is that misleading?

Kafka wasn’t extroverted and gregarious. But he went out a great deal and liked to be out in social life a lot. And he really valued friendships too. The idea of Kafka as monkishly reclusive is false. But his personality was somewhat reserved.

What was the most challenging aspect of translating these diaries?

The unfinished nature of the text. I realized that a definitive moment of certainty was not something that was going to be available to me with this translation. I also wanted to keep the text open to as broad a range of interpretations as possible.

The Diaries of Franz Kafka – Ross Benjamin (Translator)