Brazil, What Now? A Thread in the Labyrinth

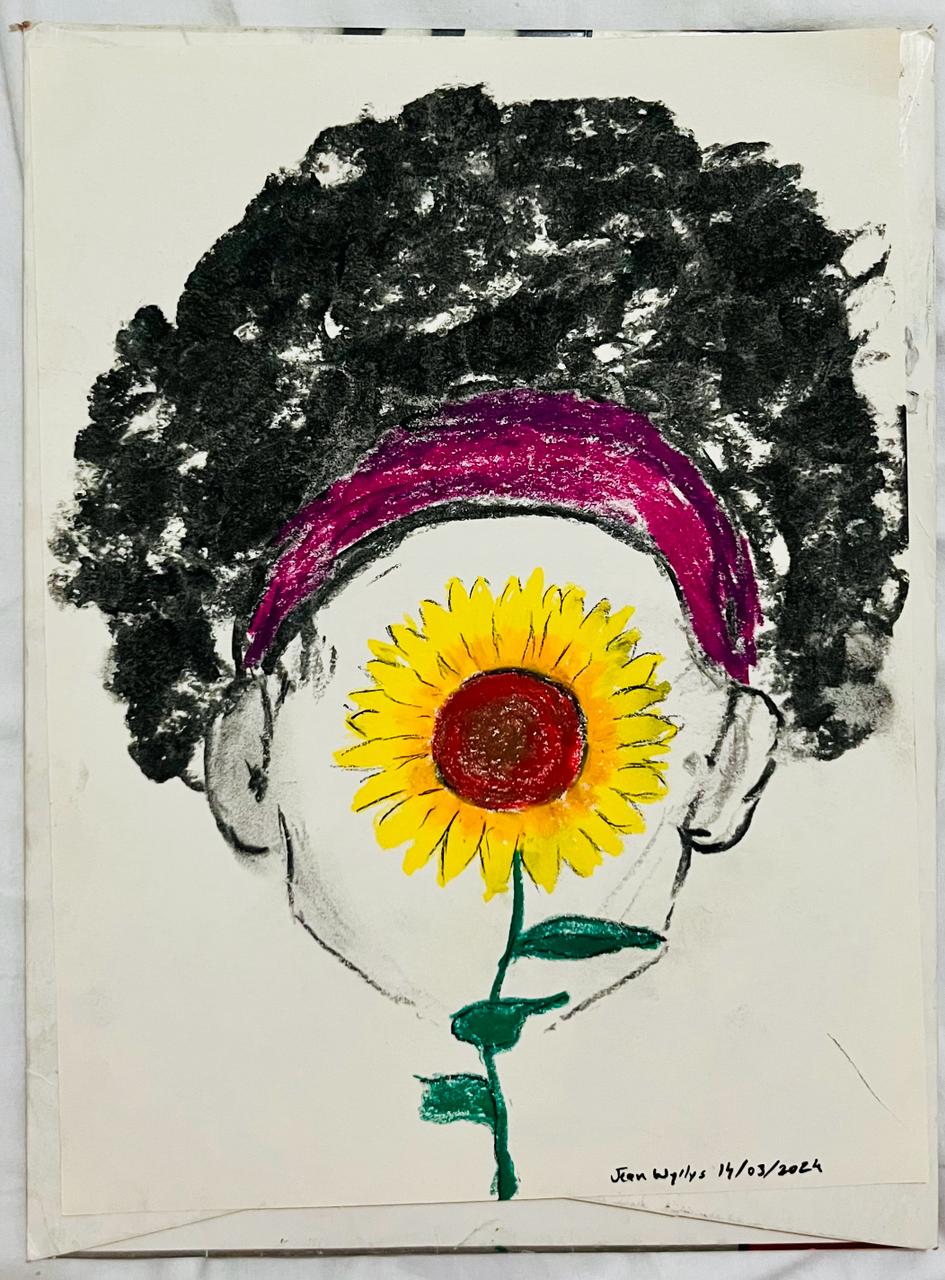

Jean Wyllys, March 2024. Charcoal and oil pastel on paper.

The thread of justice that might reweave the fabric of democracy through truth appeared in Brazil on 24 March (Day of the Right to Truth). The whole truth is far from known yet. And justice still hasn’t been done. But at least Brazil’s democratic forces have, like Theseus, started to follow the thread into the labyrinth hiding the secrets of the political murders of Rio de Janeiro councillor Marielle Franco and her driver Anderson Gomes on 14 March 2018. One crime leads to another: motive to crime to more motive to more crime. One thread leads to more threads and they knot together in the labyrinth that guards the secrets, in the form of the hideous minotaur that guaranteed the electoral victory of Jair Bolsonaro and the far right that year. We know what happened, when, where, how, and mostly why. Now the question is who? Who are the individuals constituting the monster that demanded the crime and its horrible consequences?

Ten days after the sixth anniversary of these murders, which changed the country’s history, and just over a year into the Lula mandate, the Federal Police arrested three main suspects of the murders, the brothers Chiquinho and Domingos Brazão—member of parliament and adviser to the Rio de Janeiro State Court of Auditors respectively—and Rivaldo Barbosa, head of Rio de Janeiro Civil Police, who was appointed to this position the day before the killings. Barbosa’s arrest for the political crime that he himself is supposed to investigate, is big news. The Brazão family, friends, and political allies of the Bolsonaro family, had already been mentioned independently by the press as being involved in the carefully plotted murders of the left-wing, black, gay, single-mother, grassroots organiser, human rights activist councillor from the Maré favela, Marielle Franco, and her driver, Anderson Gomes.

First bend in the labyrinth: alleged motives

According to the new Justice Minister in the Lula government, Ricardo Lewandowski, who is responsible for the Federal Police (PF), land speculation was one of the motives of the killings. The PF report notes that Marielle Franco and the Brazão brothers clashed over land use in Rio de Janeiro. Before occupying his seat in the Federal Chamber in 2022, Chiquinho Brasão, of the right-wing party União Brasil (Brazil Union) had been a Rio de Janeiro city councillor, re-elected to the same administration (2017-2020) as that to which Marielle Franco was elected for the first and only (because she was murdered) time.

The PF report describes Chiquinho Brazão’s “uncontrolled reaction” to Marielle Franco’s response in the city council to Bill 174 of 2016 on land use and the right to housing: “It was precisely this group that she opposed in the Rio de Janeiro City Council because they wanted to regulate the land for commercial use and Franco’s group wanted to use it for social purposes, in particular for housing”. Unlike his brother Domingos, who was suspected of being one of the masterminds of the crime since 2019, Chiquinho Brazão hadn’t been a person of interest in the police investigation. So, how come Domingos Brazão enjoyed impunity and freedom until Sunday 24th? The short answer is because of his relationship with the Bolsonaro family, the paramilitary, and neo-Pentecostal mafia groups that control the state of Rio de Janeiro, and the fact of his being part of the far right which was in power from the 2018 elections until the attempted military coup of 8 January 2023 just after the inauguration of Lula da Silva as president of the Republic.

In the 2018 elections, Chiquinho Brazão, like other far-right representatives, was elected to parliament as a member of the centrist Avante party and re-elected in 2022 for União Brasil. He had the full support of the Bolsonaro family, so much so that Jair Bolsonaro’s oldest son, senator Flávio Bolsonaro (conservative PL-RJ, Liberal Party of Rio de Janeiro), campaigned for Chiquinho and Domingos.

The present Director-General of the Federal Police, Andrei Rodrigues, confirmed minister Lewandovsky’s account of the motive of Marielle’s murder, adding that it had been planned since 2017. “Marielle was working with social entities and movements to inform them of their rights and the need to organise in order to have their demands met. Hence, her mandate counted on her partnership with the Public Defenders for Land and Housing Rights (NUTH) in her support for the population’s right to housing.” Chiquinho Brazão, was president of the Urban Affairs Committee in Rio de Janeiro and legislated in favour of an illegal condominium in Jacarepaguá, an epicentre of the Carioca milícias, in the western zone, which is Bolsonaro territory. New investigations have uncovered fake property deeds in two favelas of the western zone where the Brazão and Bolsonaro families operate.

Second bend in the labyrinth: shared Brazão-Bolsonaro interests

Senator Flávio Bolsonaro got rich from the illegal construction of buildings by paramilitary mafia groups, using public money squeezed by means of an extortion-cum-bribery scheme called rachadinha (from the verb rachar, to split or crack), which entails employing non-existent employees or forcing real employees, political staffers, to “donate” part of their salary in order to keep their jobs). Real-estate speculation underlies the rachadinha of Flávio Bolsonaro. Some 40% of the takings went, via hitman and former special police officer Adriano da Nóbrega, to various groups of milícias. In 2022, it was revealed that 51 of the 107 properties of the Bolsonaro family were bought with cash and, well, using big wads of money to buy property is one way of laundering resources of illegal origin. Needless to say, it’s a common criminal practice.

The rachadinha information comes from previously secret documents and data held by the Rio de Janeiro Public Prosecutor’s Office, to which The Intercept gained access. The investigations began during Jair Bolsonaro’s mandate but he managed to stall them by pressuring his then Justice Minister, Sergio Moro (União Brasil – São Paulo, currently senator and about to be tried for procedural fraud), to sack the head of Federal Police and replace him with another who would protect his eldest son, Flávio. Sergio Moro was also involved as the judge in the now discredited Lava Jato operation that unjustly sent Lula to prison and thus facilitated the election of Jair Bolsonaro, who rewarded him by making him Minister of Justice.

To add another nasty character to this story, the Brazilian journalist Bernado Gutiérrez reports that Fabrício Queiroz, former military policeman and driver of the car from which the crime was perpetrated, visited the Rio de Janeiro condominium where Jair Bolsonaro resides in number 58, just four and a half hours before the murder. He said he was going to number 58 and the gatekeeper said that someone he called “seu Jair” let him enter. Fabrício went to number 66, residence of Ronnie Lessa, retired military policeman and one of the city’s most notorious hitmen. Lessa and Queiroz left together a few minutes later. They were detained on 12 March 2019, thus giving rise to suspicion about the connection of Bolsonaro or a member of his family with the murders.

The recent arrests and imprisonment of Domingos Brazão, Chiquinho Brazão, and Rivaldo Barbosa as masterminds seems to be, in part, an attempt to take the heat off the Bolsonaro family. Indeed, Senator Flávio Bolsonaro hastened to take advantage of the news to emphasise his family’s ignorance and innocence of everything. But, you don’t have to dig very deep to find that the Bolsonaro family story is a criminal one. The milícias brought this family and the Brazão family to political prominence. As Intercept Brasil reports, the political, financial, and personal links between the Bolsonaro, Lessa, and Brazão families are “strong and undeniable”. The murders have shown more than any other political event in Brazil the Bolsonaro family’s connivance with organised crime in general.

– Ronnie Lessa, a specialist in land-grabbing, was a hitman for milícias led by former military policeman Adriano da Nóbrega, leader of the Escritório do Crime (Crime Office – investigated in 2018 for involvement in the murders of Franco and Gomes) gang of the western zone (Bolsonaro territory) of Rio de Janeiro. Nóbrega was also bagman, and parliamentary advisor to Flávio Bolsonaro, who employed his mother and wife in his Rio de Janeiro office from 2010 until 2018. When he was in prison accused of another murder, he was decorated by Flávio Bolsonaro with the Tiradentes Medal, the highest honour awarded by the Rio de Janeiro Legislative Assembly for “important services to the state”. Nóbrega was a beneficiary of the rachadinha managed from Flávio Bolsonaro’s office by Fabrício Queiros. When Nóbrega was executed by police (as he feared he would be) in February 2020 when on the run after being charged with land grabbing crimes, bribery of public officials, illegal constructions, and physical violence, Jair Bolsonaro called him a “hero”.

As the good Bolsonaro justice man, Sergio Moro did absolutely nothing to proceed with the investigations into the political assassination of Marielle Franco. In his inaction he had the full support of the neoliberal press, which said not a word in criticism of his negligence. Moro knew that, as state deputies then, Domingos Brazão and Flávio Bolsonaro were the only two members of the Rio de Janeiro Legislative Assembly who voted against the establishment of a parliamentary commission of inquiry into the milícias which run a large part of the territory of Rio de Janeiro and have pervaded all state structures. At the end of 2010, they controlled 41.5% of the city’s 1,006 favelas and drug traffickers 55.9%. By the end of 2020 they were more powerful than the drug traffickers, commanding 55.5% of the city. This wouldn’t have happened without the support of powerful politicians. The connection of milícias with the murders is clear enough. But the milícias’ political partners and protectors are yet to be officially identified. Most hitmen, like Nóbrega, come from Special Operations (BOPE) of the Military Police. Well informed of the power of milícias and their political allies, Moro did nothing to stop Domingos Brazão, who is now on trial for murder, abuse of power, and corruption, all crimes perpetrated in cahoots with the milícias, out of which came Ronnie Lessa, one of the two men who first-hand killed Marielle Franco.

By 2016, before the parliamentary coup that gave Michel Temor the presidency of Brazil, militia-style operations had spread from Río de Janeiro to Pará, São Paulo, Bahia, Ceará, Minas Gerais, Goiás, Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul, among other states. In his book República das milícias, journalist Bruno Paes Manso calls Jair Bolsonaro the real “king of the milícias”. Bolsonaro isn’t only an ideological representative of a paramilitary culture. He got to be president thanks to the milícias and thus boosted paramilitary activity throughout most of the country. “The government became an instrument of crime”.

Third bend in the labyrinth: masking evil

Rivaldo Barbosa, former head of Rio de Janeiro’s Civil Police, recently arrested plotter of the murders of Marielle Franco and Anderson Gomes, met with their families just days after the crime, wept with them, and promised he would find the perpetrators when, in fact, he was doing the exact opposite. Barbosa is no Eichmann. There’s no banality of the bureaucrat’s void of thought or inability to ponder the ethics of actions. He can’t claim he was following orders or obeying the law of the land. Barbosa’s evil is so self-aware that he disguises himself to act and counts on high-up patrons to hand him the disguise.

And here we have Jean Wyllys, one of the authors of this article, speaking in first person as he was in the thick of the events at the time. “‘We’ll never rest until this crime is solved’, Barbosa told me and other members of the External Commission of Inquiry of the Chamber of Deputies that was established at my request to monitor the investigations into the murder. I was in my second term as a federal deputy and receiving death threats from the far right as well as suffering campaigns of violent defamation. I saw that there was something wrong in this man. His mourning didn’t behove him. His snivelling sounded cheap. The tears didn’t suit him. Yet they did convince the victims’ families, who were shocked by his arrest on 24 March. Even though they’d been waiting six years for him to keep his promise.” Wyllys adds, “As a member of the External Commission of Inquiry of the Chamber of Deputies, I fought to get the inquiries to be taken to the federal level because I didn’t trust the civil police of Rio de Janeiro, but I was defeated because powerful interests resolutely acted to ensure that this was exactly where the case would remain.”

Fourth bend in the labyrinth: parliamentary coup and military intervention

Barbosa was sworn in as Chief of the Civil Police responsible for criminal investigations in Rio de Janeiro but accustomed to not solving murders (only 11% in 2023). He was recommended by two generals, Walter Souza Braga Netto and Richard Nunes, head of Public Security and Secretary of Security in the city, during the mandate of Michel Temer, whose military intervention after the 2018 Carnival was an electoral ploy to polish up his popularity as he planned to stand as a right-wing presidential candidate that year. Temer was the vice-president who betrayed President Dilma Rousseff in the parliamentary coup of 2016, when she was removed from office under the guise of impeachment for what was called a “crime of responsibility”. Rousseff, now president of the BRICS Bank, was cleared of all charges.

Known as treacherous and despite all the efforts of the neoliberal press to pretty him up, Michel Temer was extraordinarily unpopular. Understanding that public security was one of the most worrying issues afflicting the population, he decided to turn it to his advantage and puff up his reputation. He chose Rio de Janeiro, the country’s security flashpoint, suspending state autonomy and putting the army in charge, unfazed by the fact that he was messing with a narco-regime whose territories and institutions are shared out and controlled by criminal organisations. Temer’s exercise backfired.

At this stage of the game, two years after the coup against Dilma Rousseff, the Armed Forces officers who’d actively participated in it, now wanted a “thoroughbred” presidential ticket (consisting only of military men and heirs of the dictatorship that lasted from 1964 to 1985). They had a candidate who was much more popular than Temer. They had Jair Bolsonaro, former army captain, rank-and-file parliamentarian who set himself up as a free-flowing channel for all the resentments, fears, anxieties, and hatreds of the new and old middle classes, and for the huge contingent of evangelicals (more than 30% of the population) under the sway of religious sects whose leaders range from grasping charlatans to heads of large criminal organisations. These officers, speaking for retail entrepreneurs, magnates thriving on illegal mining, and agribusinessmen, all of them keen to keep stealing and plundering Indigenous land, decided after the Rio de Janeiro intervention that they had to seize power. Their man was media-savvy and an enemy of truth. Bolsonaro and his sons were well tutored in digital misinformation and aided by the international far-right, especially Steve Bannon, and they counted on the indulgence of the neoliberal press. Proof of international support from far-right extremists is The New York Times report that Bolsonaro hid out for a couple of days in the Hungarian embassy last February, after two of his close aides were arrested on suspicion of plotting a military coup on 8 January 2023 after Bolsonaro lost the 2022 presidential election.

As federal Interventor in the Public Security of the state of Rio de Janeiro, General Braga Netto signed off on the appointment of Rivaldo Barbosa as Chief of Police, although this was counter-indicated by intelligence sources. Why? This is one of the questions now being asked in the public arena. Still clinging to the thread of justice so we don’t get lost in the labyrinth of this political crime, we summarise what we find so far. The traitor president Temer names Braga Netto as Federal Interventor in Rio de Janeiro at the suggestion of the army commander who was with him in the 2016 coup against Dilma Rousseff. Braga Netto approves the appointment of former military man and state deputy Rivaldo Barbosa as Chief of Police in the state of Rio de Janeiro. At the request of the Brazão brothers—allies of Jair Bolsonaro, military candidate for the 2018 elections on its “thoroughbred” and demagogical fascist platform, fake-news-fuelled by a well-run digital ecosystem of harassment and disinformation—Barbosa not only plans the killing of Marielle Franco but is also named as chief “investigator” or, in other words, chief hindrance in the inquiry into the bespoke murders. The Brazão brothers campaign for Bolsonaro and he campaigns for them. Bolsonaro appoints Braga Netto as his Chief-of-Staff and eventually Defence Minister.

If solving the crime depended on the neoliberal press, justice would never be done. It can only happen with the involvement of people like Marielle Franco who fight disinformation, sabre-rattling, and cowardice in politics and journalism. In electoral terms, the far-right directly benefitted from the execution of Marielle Franco and Anderson Gomes because the “thoroughbred” slate won the elections partly because of the fear generated by this well-planned violence. We can’t be satisfied with the only motive the Federal Police have given for the murders.

Fifth bend in the labyrinth: digital political defamation

Barely hours after the killings, the far-right’s disinformation/defamation machinery swung into action to malign Marielle Franco and invent false motives of her execution by a machine gun blast that destroyed her face. As part of the fake news, the crime was invisibilised. The security cameras weren’t working that day. On the fake news bandwagon was the far-right Movimento Brasil Livre (MBL – Free Brazil Movement) which worked with its allies in other countries, especially the United States Many of its members were elected in 2018 thanks to its slandering of Marielle Franco, and its obfuscation of the putschist Temer’s military intervention in Rio de Janeiro under the command of General Braga Netto. Two senior public appointees, the Rio de Janeiro judge, Marília Castro Neves and federal deputy Alberto Fraga of the conservative Liberal party, recently elected president of the Public Security Committee of the Chamber of Deputies, are still using social media accounts to give credit to the MBL and other far-right lies about Marielle Franco. If there is to be truth and justice, all these connections must be identified and followed wherever they lead because this smearing of Marielle Franco six years after she was murdered is no mere chance. It has clear purposes, mainly to obstruct the investigations and help to elect and keep in power those who benefitted politically from the crime.

The end of this story is just beginning. There is only a thread to guide us in this labyrinth. We still can’t identify all the people who come together in the many-faced monster lurking in its depths, still doing its damage. There was a third person in the car from which the shots were fired against Marielle Franco and Anderson Gomes. Who was he? What are his connections with the other two executioners? Did he want to ensure that the killing was thoroughly done or was he a sadist there to witness the death of a political enemy, or both? As long as the questions are unanswered the monster will remain alive and active, needing more human sacrifices to nourish its ugly existence.

The murders of Marielle Franco and Anderson Gomes were a crude mechanism for protecting illegal real-estate and other criminal interests of milícias and their political allies. If Bolsonaro’s government “became an instrument of crime”, then the highest levels of political and economic power are at the heart of the labyrinth concealing the secrets of the murders of Marielle Franco and Anderson Gomes. The thread of truth and justice will need to be very strong if this monster is to be removed from its lair.