Destroy Hamas? No, End the Gaza War and Begin the Peace Process!

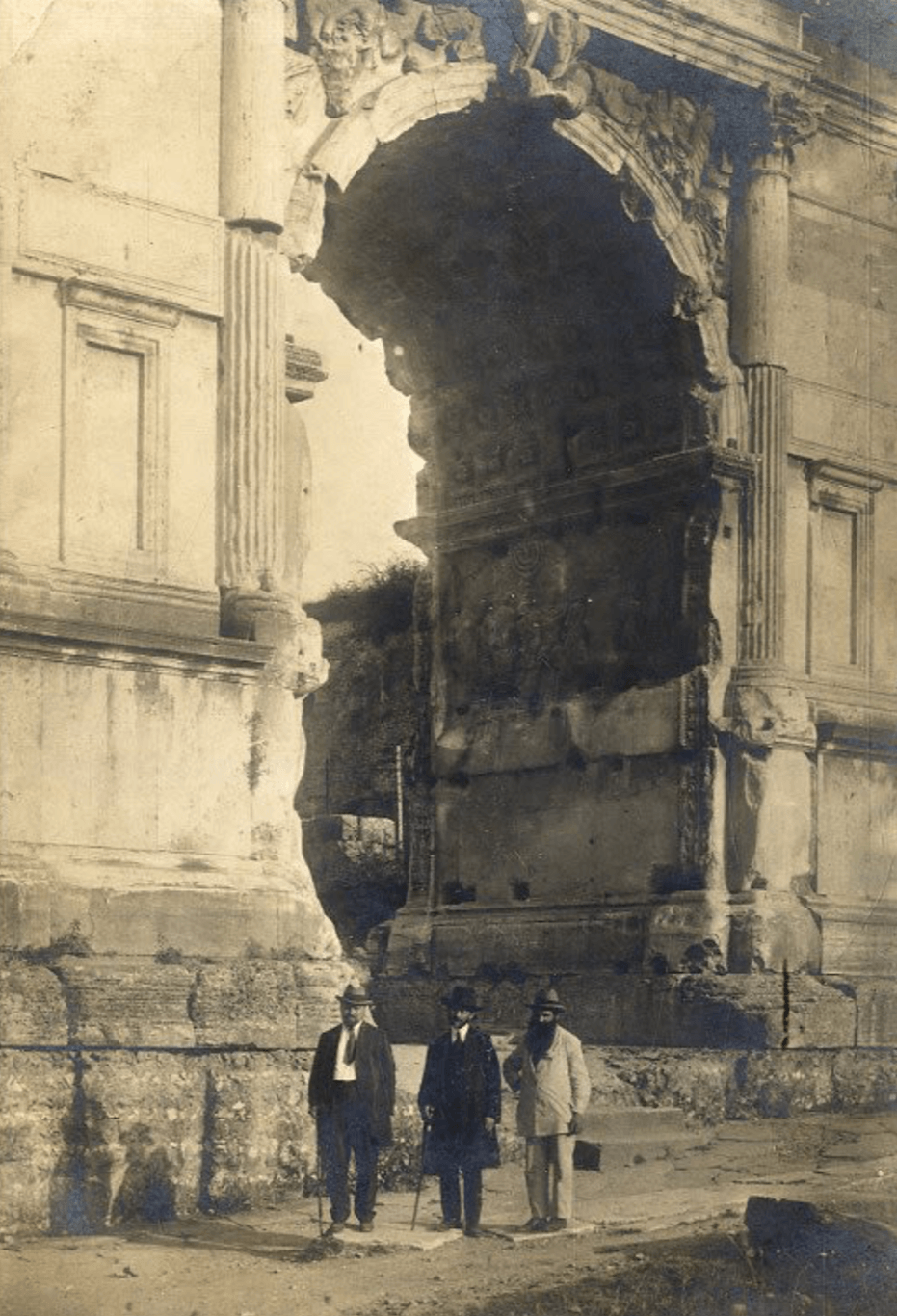

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

David Brooks has written a lengthy New York Times article on the war in Gaza that boils down to one proposition: “If this war ends with a large chunk of Hamas in place, it would be a long-term disaster for the region” (“What Would You Have Israel Do to Defend Itself,” 3/25/24).

Unless Hamas is destroyed, Brooks argues, Hamas will dominate the postwar government of Gaza and launch more attacks on Israel, and “it would be impossible to begin a peace process.” Benjamin Netanyahu, who calls for the “total destruction” of Hamas, agrees.

Without doubt, attempting to eliminate Gaza’s largest political and military organization will intensify the catastrophic destruction of lives and environment already branded plausibly genocidal by the International Court. According to Brooks, this compels a “tragic conclusion”: too bad, but “there is no magic alternative military strategy.” Clearly, the columnist does not want to act as an apologist for war crimes, but he does so here. Why? Because he assumes that Hamas is entirely dedicated to the destruction of Israel’s Jews and that its leaders and members are incapable of altering this motivation.

Does this assumption make sense? The evidence of history, as well as our knowledge of the Palestinian national movement, strongly suggests that it does not. Believing that an opponent is unchangeably dedicated to one’s annihilation reflects the traumatized consciousness of one involved in a bloody conflict rather than a thoughtful appreciation of the real situation. Hamas certainly wants to change the political system that systematically privileges Jewish Israelis and oppresses Palestinians, but its leaders have made it clear that they oppose “racist, aggressive, colonial and expansionist” Zionism and do not hate Jews as Jews.

It is ferociously difficult, of course, to accept the idea that a militant group responsible for killing one’s friends, relatives, neighbors, and co-nationals can become a nonviolent competitor and even a partner for peace. People often hate their adversaries and seek to make them suffer, fear their violence and seek to deter it by rendering them helpless. Nevertheless, following bold and creative peace negotiations, the parties to atrocious violence in conflicts around the world have learned to live with former enemies they had reason to hate and fear.

In Northern Ireland Catholic Republicans and Protestant Unionists learned to share power even though organizations like the Irish Republican Army and Ulster Defense Alliance had both massacred “enemy” civilians. Black and white South Africans agreed on a new political order even though militants of the African National Congress and the National Party had terrorized each other for decades. The combatants in bloody civil wars in Liberia, Mozambique, Colombia, Bosnia, Lebanon, Nepal, Cambodia, and many other locales managed to develop mostly nonviolent political and social relationships even though this meant backing off from earlier vows to “totally destroy” their adversaries.

Can this happen in Israel/Palestine? As intractable as that conflict seems, its own history strongly suggests that it can. Israelis long considered the Palestine Liberation Organization headed by Yasir Arafat an irredeemably hostile adversary – so much so that they supported the growth of Islamist groups like Hamas as counterweights to PLO power. (The U.S. resorted to a similar strategy to counter Russian forces during the U.S.S.R.’s war in Afghanistan.) But in 1988, after serious negotiations, the PLO recognized the State of Israel and participated in further talks that produced the Oslo Accords of 1993.

When violent conflict returned to the Holy Land several years later, each of the parties blamed the breakdown of relations on the other side’s incurable malice. Israel’s prime minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by a Jewish extremist, and his successor, Netanyahu, undermined the two-state solution contemplated by the Accords. Terrorist attacks against Israeli civilians were mounted by extremist Palestinian organizations like Islamist Jihad and the Fatah Martyrs Brigade. Even so, extremism was more a symptom than a cause of the breakdown of the Oslo system. What was at fault was the system itself, which did not begin to solve fundamental problems such as massive Jewish settlement of the occupied territories, Palestinian claims to a right of return or compensation for lost lands, the status of East Jerusalem, the unequal treatment of Jews and Palestinians, and more.

Similarly, as UN Secretary-General Guterres noted, Hamas’s resort to violence in October 2023 “did not take place in a vacuum.” It followed 16 years in which Gaza was blockaded by Israel, rendering it one of the poorest and most unfree urban settlements on earth, and after four prior wars of relatively short duration had killed more than 2,000 Palestinian civilians. The Hamas leadership bears responsibility for the horrific attacks of October 7 and the Israeli leadership for the IDF’s wildly disproportionate response, but the causes of the war lie in a structurally violent system that systematically favors the vital interests and needs of Israeli Jews over those of Palestinians in Israel and especially in the occupied territories.

To make a peace that lasts, systems like this need to be changed. Conflicts in which warring parties later learn to live together nonviolently are generally resolved by negotiations that create new institutional arrangements offering to provide all parties with security, recognition, a means of self-expression, and a method of sharing power. This is what the Oslo processes hoped to do but failed to accomplish because negotiators did not consider, in a situation of severe power asymmetry, how genuine power-sharing might work.

According to some commentators, this failure to consider a more egalitarian systems is, at bottom, the result of Zionism – an ideology and practice that defines Israel as a Jewish state obliged to subordinate the rights of other groups inhabiting the territory to those of Jewish residents and potential residents. Others believe that it is possible to reconcile the principles of Zionism with those of democratic pluralism, for example, by implementing a more robust version of the “two-state solution” originally contemplated by the architects of the Oslo process. In either case, sustainable peace between Israelis and Palestinians will depend upon both parties agreeing to consider serious changes in a conflict-generating system.

Furthermore, if peace negotiations are to take place in order to avoid an endless war in Gaza that spreads to the West Bank and to the entire region, each side must be free to choose its own representatives. Just as the Israelis will decide whether to be represented by the current ruling coalition or some other spokespeople, the Palestinians will decide whether Hamas, the Palestinian Authority, or the members of some coalition yet to be formed will speak for them. Very likely, Hamas will not sit at the table as the sole Palestinian negotiator but, considering that its leaders are vastly more popular and trusted than those of most other organizations, figures associated with that group will surely play an important role.

“Totally destroy” Hamas? To begin with, there is the question whether this is possible. The Islamic State was declared defeated in 2019 when it lost the last piece of its self-declared Caliphate, but ISIS is estimated to have 5,000-7,000 fighters at present in Syria and Iraq, with an undetermined number in Afghanistan and other locales. Even if it were possible to eliminate Hamas as a fighting force (at the cost of killing thousands more Palestinians and alienating their friends and descendants), eliminating them as negotiators would very likely doom any meaningful peace process.

Ironically, this is the opposite of David Brooks’ declaration that unless Hamas disappears, a peace process will be impossible. Contrary to the popular belief apparently shared by Brooks, violent civil struggles are seldom resolved effectively by getting the moderates on both sides to reach a compromise. This, in effect, is what happened at Oslo. On the contrary, system changes that are needed to resolve “intractable” civil conflicts depend upon dialogues that include popular militant groups, as negotiations in Northern Ireland, Mozambique, South Africa, and elsewhere have shown. Peace talks capable of ending the structural violence that generates such wars must involve forces capable of criticizing and reconstructing failing systems, that is, groups that begin as violent rebels (“extremists”) against the existing order.

We can agree, perhaps, that violent rebels who attack civilians should be found and punished, as many leaders and members of Hamas have already been. By the same token, violent repressors who massacre civilians and commit war crimes should also be found and punished, as some Israeli leaders and IDF fighters should be. But peace will depend upon representatives of both sides, including some with bloodstained hands, agreeing to change an inherently violent system.

Since that system includes the United States as a financier and manipulator of Middle Eastern groups in conflict, the U.S. government may be giving little more than lip service to the goal of significant change in Israel/Palestine. The Americans have been talking in Oslo-like terms of reviving the two-state solution, but their apparent plans to continue financing the war against Hamas and to put the Palestinian Authority (or the Saudis!) in charge of Gaza suggest that they are determined to maintain their imperial hegemony in the region come what may.

Destroying Hamas, it seems clear, is not the road to peace. Since sustainable peace in the Middle East depends on system changes that satisfy all parties basic needs, the fate of militant Palestinian organizations in Gaza and the West Bank is intimately linked to the creation of a genuine peace process as opposed to an ineffectual sham. For this as well as humanitarian reasons, it is long past time for the killing of both civilians and fighters in Gaza to end.