Largest-Ever Climate Poll Shows 64% of Global Public Believes Warming Planet Is an 'Emergency'

"The voice of the people is clear—they want action on climate change."

A young girl stands in Jiangtan park after it was flooded by heavy rains along

the Yangtze river on July 10, 2020 in Wuhan, China. (Photo: Getty Images)

Nearly two-thirds of people around the world think climate change is a global emergency that warrants a serious response, according to the results of the Peoples' Climate Vote, the largest survey of public opinion on the planetary crisis and policy solutions ever conducted.

"The results of the survey clearly illustrate that urgent climate action has broad support amongst people around the globe, across nationalities, age, gender, and education level."

—Achim Steiner, UNDP

"Recognition of the climate emergency is much more widespread than previously thought," Stephen Fisher, a political sociologist at the University of Oxford and co-author of the report, said in a statement released Wednesday. "We've also found that most people clearly want a strong and wide-ranging policy response."

Fellow co-author Cassie Flynn, the strategic adviser on climate change at the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), told The Guardian that "the voice of the people is clear—they want action on climate change."

Survey data were gathered from 1.2 million respondents in 50 high-, middle-, and low-income countries covering 56% of the world's population, thanks to what the UNDP called a "new and unconventional approach to polling."

As the report explained, "Poll questions were distributed through advertisements in mobile game apps in 17 languages, which resulted in a huge, unique, and random sample of people of all genders, ages, and educational backgrounds."

The findings, Flynn noted, should be interpreted by elected officials as a call to take the robust action necessary to avert catastrophic warming and irreversible damage to ecosystems.

"If 64% of the world's people are believing in a climate emergency then it helps governments to respond to the climate crisis as an emergency," said Flynn. "The key message is that, as governments are making these high-stakes decisions, the people are with them."

Data were collected between October and December 2020, and even amid the Covid-19 pandemic, 59% of the people who believe there is a climate emergency also said governments should "do everything necessary and urgently" in response.

Though recognition of climate change as a global emergency was widespread in every region, there was some variation according to geographical and economic characteristics. Acknowledgement of the climate emergency was highest in Small Island Developing States (74%), followed by high-income countries (72%), middle-income countries (62%), then Least Developed Countries (58%).

Biggest ever survey finds two-thirds of people think climate change is a global emergency - 1.2 million people in 50 countries were polled. Politicians and business leaders: the time to act decisively is now! #climatecrisis https://t.co/NNgdmFtGVY pic.twitter.com/l7BmkTeJYj

— Stefan Rahmstorf (@rahmstorf) January 27, 2021

Presented with 18 climate policies—spanning energy, economy, transportation, food and farms, nature, and protecting people from environmental impacts—survey respondents were asked which ones governments should enact to confront the climate emergency.

As The Guardian noted:

Even when climate action required significant changes in their own country, majorities still backed the measures.

In nations where fossil fuels are a major source of emissions, people strongly supported renewable energy, including the US (65% in favor), Australia (76%) and Russia (51%).

Where the destruction of forests is a big cause of emissions, people supported conservation of trees, with 60% support in Brazil and 57% in Indonesia.

Overall, the most popular actions to tackle the climate crisis were protecting and restoring forests, followed by renewable energy and climate-friendly farming. The promotion of plant-based diets was the least popular of the 18 policies in the survey, with only 30% support.

People between the ages of 14 and 18 expressed the greatest level of concern, with 69% in that cohort saying there is a climate emergency. A smaller majority—58%—of those aged 60 and over agreed.

"70% of people under 18 believe climate change is a global emergency"

Across all age groups it's 64%

So why are governments and the EU treating the #ClimateCrisis like something we can deal with in a few decades' time?https://t.co/0jDeNPZvlJ

— Greenpeace EU (@GreenpeaceEU) January 27, 2021

As Common Dreams reported late last year, pandemic-driven economic shutdowns have not deterred the climate emergency. Despite a slight downtick in annual greenhouse gas emissions, global temperatures reached record levels and disasters continued to increase in frequency and intensity in 2020.

Yet there is a significant relationship between the coronavirus crisis and the U.N.'s global climate poll. As the UNDP explained, "Many of the policy choices in the Peoples' Climate Vote—whether relating to jobs, energy, protecting nature, or company regulation—speak to issues that countries are facing as they chart their recoveries."

"Many of the policy choices in the Peoples' Climate Vote... speak to issues that countries are facing as they chart their recoveries."

—UNDP

The survey reveals that a majority of the world's population is worried about and wants public policies to address the climate crisis at precisely the moment when governments have been given an opportunity to pursue transformative agendas to create more sustainable societies.

"The results of the survey clearly illustrate that urgent climate action has broad support amongst people around the globe, across nationalities, age, gender, and education level," UNDP administrator Achim Steiner said in a statement. "But more than that, the poll reveals how people want their policymakers to tackle the crisis."

"From climate-friendly farming to protecting nature and investing in a green recovery from Covid-19, the survey brings the voice of the people to the forefront of the climate debate," Steiner added. "It signals ways in which countries can move forward with public support as we work together to tackle this enormous challenge."

With November's U.N. climate summit approaching, politicians must soon agree upon a more ambitious international plan to mitigate and adapt to the global emergency.

"These perspectives are needed now more than ever as countries around the world are in the process of developing new national climate pledges—known as Nationally Determined Contributions or NDCs—under the Paris Agreement," the UNDP wrote. "As the world's largest provider of support to countries for NDC design, UNDP has found that a key factor for countries raising levels of climate ambition is popular support for policies that address climate change."

President Joe Biden's climate envoy John Kerry on Monday told world leaders at the virtual Global Adaptation summit that countries should "treat the crisis as the emergency that it is" by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, or else expect, "for the most vulnerable and poorest people on Earth, fundamentally unlivable conditions."

As The Guardian reported at the time, Kerry "warned that the costs of coping with climate change were escalating, with the U.S. spending more than $265 billion in one year after three storms."

"We've reached a point where it is an absolute fact that it's cheaper to invest in preventing damage or minimizing it at least than cleaning up," Kerry said. "We have to mobilize in unprecedented ways to meet this challenge that is fast accelerating, and we have limited time to get it under control."

"We are at a fork in the road," Flynn said, "and the poll says 'this is how your future generations are thinking, in specific policy choices'—it brings a way to envision the future."

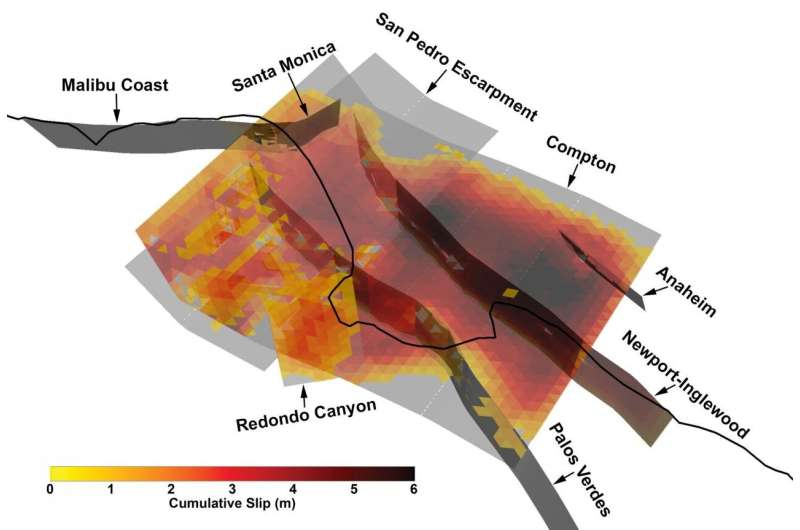

A randomly selected 3,000-year segment of the physics-based simulated catalog of earthquakes in California, created on Frontera. Credit: Kevin Milner, University of Southern California

A randomly selected 3,000-year segment of the physics-based simulated catalog of earthquakes in California, created on Frontera. Credit: Kevin Milner, University of Southern California