Chess: 12-year-old Abhimanyu Mishra breaks youngest grandmaster record

The American beat Sergey Karjakin’s 2002 mark in Budapest to take the record that has been held by Boris Spassky, Bobby Fischer and Judit Polgar

One of the most enduring chess records, Sergey Karjakin as the youngest grandmaster ever at 12 years seven months, was finally broken on Wednesday afternoon. Abhimanyu Mishra, from Englishtown, New Jersey, US, who was already the youngest ever international master at 10 years nine months, achieved his third and final GM norm at 12 years four months. Mishra achieved the 2500 rating requirement a few weeks ago, and his title will soon be confirmed by Fide. Mishra learned to play chess at two-and-a-half and became the youngest ever US expert at seven.

Karjakin’s record had narrowly survived serious attempts by India’s current generation of talents, but Mishra’s concentrated campaign, launched after the pandemic derailed his competitive play for the best part of a year, reached its target with 66 days to spare. His father’s key move was a one-way air ticket from the US to Budapest, which currently has a continuous series of GM and IM tournaments.

Mishra has been in continuous action there since April, scoring all three needed GM norms (performance levels at 2600) plus a 2500 overall rating. In fact, he overachieved. Budapest First Saturday in May was his most impressive result, where he simply ran away from the field, scoring an unbeaten 8/9 with a winning margin of three points.

His tournament performance rating (TPR) was 2735, the level of the world top 20 grandmasters. It was almost certainly the youngest 2700+ TPR in chess history, and the first ever by a preteen. His final-round win there, with first prize and GM norm already secure, is one of his best so far.

Mishra was interviewed on Thursday by a team including England’s GM David Howell and No 1 woman IM Jovanka Houska. To the question: “Where does he go from here?” his father, Hemant, said after Abhimanyu became the youngest IM they expected him to break Karjakin’s record by a wide margin, only for the pandemic to stop all over-the-board activity for several months. Hence the crash course in Budapest, where Mishra played virtually non-stop for many weeks with at most a day’s break between tournaments and sometimes two rounds a day.

The GM age record is viewed by the Mishras as just a step on the real target for Abhimanyu’s teen years, to break the records for reaching 2600 (strong GM) and 2700 (elite GM). Several players have passed 2600 strength at 14. Arguably, Bobby Fischer was the first and still the most impressive when he won the 1957-58 US championship, long before the rating system began in 1970.

At 2700, elite GM, the youngest have been China’s Wei Yi at 15 years eight months and Iran-born Alireza Firouzja at 16 years one month. Again, Fischer deserves a mention for his performances at 15 in the 1958 Portoroz interzonal and the 1958-59 US championship.

Youngest GM became official only in 1950, when Fide issued its first list of titles. David Bronstein was then the youngest at 26, followed by Tigran Petrosian at 23 in 1952, Boris Spassky at 18 in 1955, and Bobby Fischer at 15 in 1958. The last three all became world champions. Fischer held the record for over 30 years before the all-time No 1 woman, Judit Polgar, broke it in 1991, after which it was gradually lowered until Karjakin, then of Ukraine and now Russia, took it in 2002.

Karjakin, who went on from being a prodigy to challenging for Carlsen’s world crown in 2016, had gracious words for the new record holder: “I am quite philosophical about this because it has been almost 20 years. It had to be broken sooner or later. I was sure one of the Indian guys would do it much earlier, and I was lucky that it didn’t happen.

I am a little sad that I lost the record, but at the same time I can only congratulate him and it’s no problem. I hope that he will go on to be one of the top chess players and that it will be a nice start to his big career.”

Mishra will now travel to the 206-player World Cup in Sochi starting on 10 July, where Carlsen is the top seed and the 12-year-old has been given a wildcard entry by Fide. His first-round opponent is Baadur Jobava, three times champion of Georgia and famed for his imaginative attacking style. An unlikely victory there would put him in the second round against the former US champion Sam Shankland, ranked world No 31 after his recent victory in Prague.

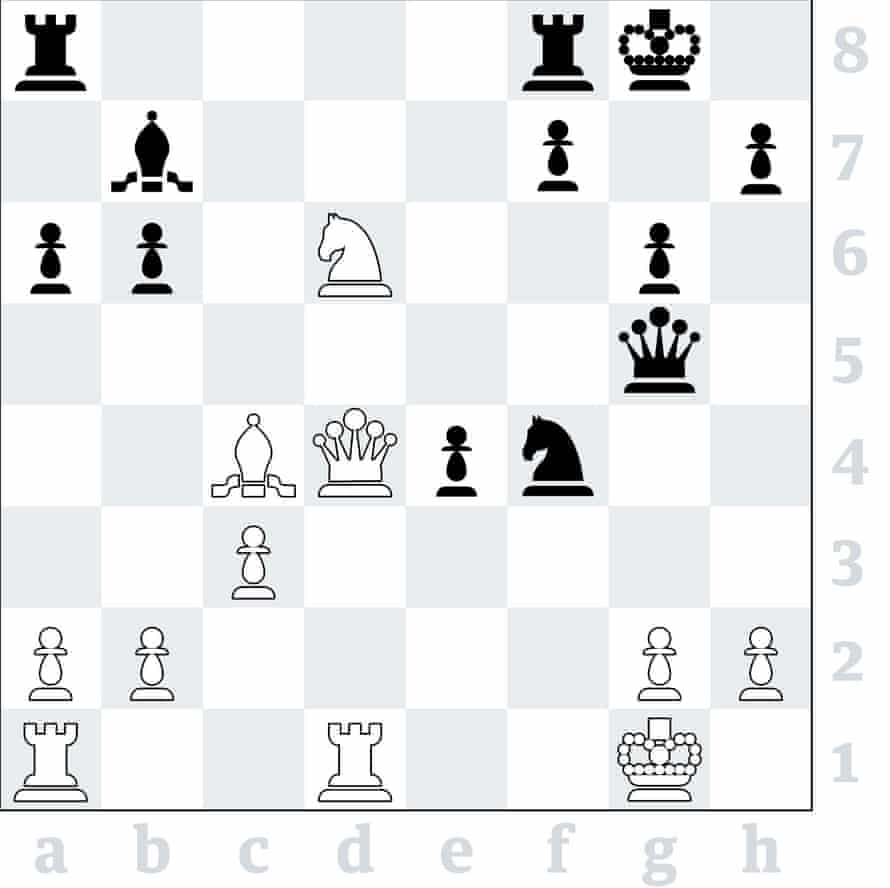

3730 Bxf7+ Rxf7 2 Qh8+! Kxh8 3 Nxf7+ and 4 Nxg5 wins easily on material. The famous precedent is Tigran Petrosian v Boris Spassky, 10th world championship match game 1966.

.png)

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

Credit: CC0 Public Domain