ESSAY: ART VERSUS STATE VIOLENCEPublished December 25, 2022 Updated about 7 hours ago

Pakistan, in its short history, and the land and its people in its longer colonial history, has seen its share of violence. As a country that has been subject to intermittent oppressive military regimes and a political arena based on ethnic and religious divisions, the state has been both victim and perpetrator of violence — ranging from the blatant and outright, to the more sinister oppressive practices, at times hidden in plain sight as completely legitimate policies.

The city of Karachi, especially, becomes a microcosmic of the long bloody history of violence that the citizens of Pakistan have been subjected to, from street crime to extortion rackets by militant wings of religious and political parties. Its citizens, especially those in the lower income areas and the poor indigenous people on the peripheries of the city, live in a constant state of fear of the political elite, and even the authorities that are often either involved or turn the other cheek.

In the book Art, Violence and the State in the Killing Fields of Karachi, art critic Quddus Mirza aptly likens the relationship between art and the state to an abusive marriage. The book, conceived by Adeela Suleman and Mariam Ali Baig, delves deep into the 444 extrajudicial killings carried out in 192 alleged fake encounters by former SSP Rao Anwar Ahmed Khan between 2011-2018, the art installation by Adeela Suleman titled ‘The Killing Fields of Karachi’ (2019) for the Karachi Biennale 2019 (KB19), and the subsequent destruction of this artwork by the authorities in an act of blatant, violent censorship and suppression.

Fahim Zaman Khan and Naziha Syed Ali detailed Anwar’s criminal operations in a Dawn report that is included in the book, stating, “The former SSP was the head of a vicious cabal, including cops and local thugs… anyone who crossed them or refused to pay was picked up, detained and tortured, sometimes even killed in fake encounters.”

Adeela Suleman pictured in her workshop, surrounded by her team of metal workers | Stephan Andrew

According to this report, Anwar was running multiple rackets, including extortion of protection money, land grabbing and a land mafia mining and selling sand and gravel from public land.

Anwar was able to evade all inquiries into his extrajudicial killings as he is thought to have been protected by powerful figures in the government and even the establishment, who not only allowed him to continue his business, but actually nurtured him as an asset.

A recent book helps explore the relationship between art and the state through the lens of violence and censorship

Right up until he perhaps started to become a liability. That might be one of the reasons the case of Naqeebullah Mehsud, the 27-year-old Pakhtun father of two abducted and murdered by Anwar in 2018 at an abandoned poultry farm in the outskirts of Karachi, became his undoing.

Claims of Naqeebullah’s ties to the terrorist group Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) contradicted images of his going viral in the media, showing a handsome young man with beautiful long hair and dreams of becoming a model.

It was this image that caught the imagination of the nation, which quickly rallied behind his father, Muhammad Khan’s protests in pursuit of justice. Naqeebullah became the face of the countless victims of encounter killings which propelled the mobilisation of a nation.

“One of Anwar’s victims had been humanised, and no one could look away,” says Human Rights activist Jibran Nasir in ‘A Death Foretold’.

However, even as the case against Anwar gained strength in what lawyer Faisal Siddiqi describes as “lightning speed and unexpected directions” in his essay ‘The Art of Justice’, where he identifies the chain of events as they happened, nothing became of it.

Rao Anwar SSP District Malir, Karachi — the ‘encounter specialist’

| Dawn Archives

Once public interest and outcry faded, the case started losing strength, as Anwar was granted bail, witnesses retracted statements and evidence began to disappear, and he ran free.

“The state knows that a guilty verdict on Naqeebullah’s murder would give social, political and, to a great extent, legal legitimacy to claims regarding the state’s abetment of unconstitutional abductions and extrajudicial killings,” says Nasir.

Violence and Art

In a country where most people have become desensitised by the routine violence, it is the artists who return our focus to what is important. Art has had a longstanding fascination with human suffering and misery, almost to the extent of fetishism in certain cases.

Throughout art history, artists have focused on violent imagery, horror, pain and grief, from elements of violence found in the Lascaux caves of wild beast hunts to 15th-16th century art rife with violent imagery from myths, legends and religious scripture alike.

The painting “Judith Beheading Holofernes” (1598–1599 or 1602) by Caravaggio, for instance, turns the graphic depiction of blood and gore into a thing of beauty, at once repulsive and enticing.

In recent years, artists have sought to question and comment on this proclivity, such as in many of the works by Rashid Rana, most potently with his series ‘Flesh and Blood’ (2009), which explores the link between sex and violence.

Adeela Suleman’s entire practice focuses on the ways in which violence is an everyday part of our lived experience and visual landscape, and by aesthetising it, she comments on our desensitisation and apathy towards — and at times even a dark enjoyment of — it.

She delves deeper into this phenomenon in her essay ‘Towards Mayhem’, declaring that, “The more odious the act, the more compelling it becomes for actors and observers alike… the more heinous the crime, the more captivating and beautiful the monument to it.”

A major critique of this is the perpetration of the very concept being critiqued, the act of combining beauty and violence resulting in its palatability, and a further normalisation of the horrors in society. Victims are dehumanised and there is a dissociation from the crime, as it almost becomes a source of entertainment, packaged as an object, rather than a violent act or mournful event, undercutting the gravity of such incidents.

Adeela Suleman, ‘Untitled VI’

Most recently, Netflix crime dramas, specifically Dahmer — Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story (2022) was criticised for exactly this reason. In this way, art becomes complicit in the crime, the indirect perpetrator of violence.

In some works, the violence becomes even more direct and performative, such as in Ai Wei Wei’s “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn” (1995), where the destructive act is the art. Paradoxically, the destroyed object acquires a new meaning and significance as it transforms into another form and work of art, enduring even as it loses its physical presence. In this way, the act of destruction is also an act of creation.

What makes pain and violence so compelling to the artist? Why do they find beauty in it? Is it that it is such a universal part of the human experience, or that in the reminder of death we are most alive? Is it a twisted sense of sadistic pleasure, or a sense of power, derived from instigating an emotive response from others? Or perhaps it is the belief that only through suffering can we truly understand and appreciate the meaning of life, a problematic view held by many proponents of war.

All these elements came together in Adeela Suleman’s installation at the Karachi Biennale 2019 (KB19), ‘The Killing Fields of Karachi’ (2019), which memorialised the victims of extrajudicial killings carried out by Anwar.

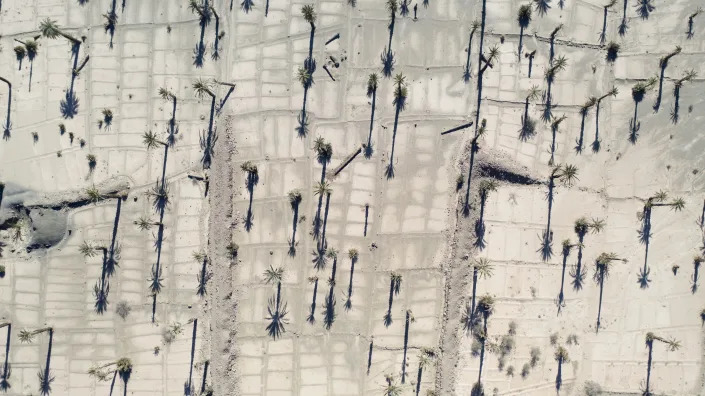

With Naqeebullah and his father as the prime focus, Suleman’s work aimed to remind us of these injustices, with 444 pillars standing almost as tombstones outside and inside the Frere Hall, one of the KB19 venues. The wilted metal roses atop these pillars again linked beauty and death.

However, the work did not look at the tragedy with an outsider’s patronising gaze, but gave voice to the victim and his family, almost in a collaborative capacity through the video and photographic components, and perhaps even a sense of closure, by honouring the victims through remembrance. At the same time, it is a point of awareness for the audience. In this sense, the recreated violence was not purposeless and, in fact, served the victims; rather than being complicit, it countered the perpetrators.

However, the work stirred controversy within two hours of its opening, as it was forcefully shut down by the authorities and, in the next two days, it was destroyed, hauled into Karachi Metropolitan Corporation (KMC) trucks and carried away. This violence inflicted upon the artwork was meant to silence these 444 voices once again, but became an inadvertent performance that, instead, added a new dimension to the work.

An installation that would’ve been viewed by a few hundred people — art being a niche interest in Pakistan — had now reached millions around the globe, making international news and becoming part of mainstream discourse. It was immortalised through images and the story behind it shared widely on social media, and the injustice spurred a round of performative protests from members of civil society and the art community.

Adeela Suleman ‘Statecraft of Violence’ (2021-2022) | Ghalib Hasnain

Much like Ai Wei Wei’s performance, here too, the erasure granted the work more visibility and through its own destruction, it is now permanently etched on to the pages of art history, to be discussed and dissected for years to come.

What would perhaps have merely been an artwork, viewed and appreciated in the moment, has now become a significant political event, where civil liberties came under attack. It sought to remember the victims of injustice, and now it will itself be remembered as a monument to the injustice it endured.

Art and Censorship

Art and the state are inextricably linked by their relationship with violence. Art reveals certain truths about life and human nature through its portrayal of violence, while the state instigates violence to silence these threatening truths.

“The provision of justice or other basic services is of no interest to the government. As the state is becoming weaker, it is becoming more authoritarian,” says Faisal Siddiqi. In order to hide this weakness and re-establish its power, an exercise of control is needed. This manifests in the form of censorship in one form or another and, thus, censorship itself can be a form of violence inflicted by the state.

But why does the state target the arts in a country where its audience is fairly limited, and their efforts merely fan the flames? In the case of Suleman’s installation, it is even more perplexing, as the artist states that it was merely a reiteration of facts already in public knowledge, adding nothing new to the discourse.

She feels it is due to the same reason Naqeebullah’s case captured the attention of the nation — the power of the image. This power of art to influence opinions and rile up the nation challenges the power of the state, and thus it retaliates to re-assert its hold.

However, it is also the subjective nature of art, and its position as the response of an individual that, in turn, draws an emotive response from the audience. It is not presented as cold facts in media reports, and is not backed by multiple powerful media corporations with their own political backings, but a defenceless citizen presenting an opinion, even if in subtext. While Suleman insists she is simply telling a story, the way this story is presented takes a stance that threatens those involved in the crime and instigates a defensive reaction.

Furthermore, while the artist insists her work is a memorial and not a protest, the idea of memorialising such tragedies, in itself is an act of defiance and resistance, when the perpetrators rely on our propensity to forget and move on to grant them impunity.

Adeela Suleman pictured at the ‘die-in’ protest | Marvi Mazhar

“We live in a society that believes in forgetting acts of brutal state violence,” writes Faisal Siddiqi and that it was the initial mobilisation by civil society that overcame the fear surrounding Anwar’s accountability and sustained the legal battle against him. It was only when this mobilisation lost traction that he was able to slip away. Memorials help us remember, and this remembering becomes a form of silent protest, and so the authorities did not like the idea of Suleman reminding us yet again.

While the attempts at silencing her backfired, its long-term effects are still detrimental to the arts, creating a culture of fear that leads to even more self-censorship. Suleman says, “Here it is important to note that, even when such efforts do not actually suppress particular types of expression, they cast a shadow of fear, which leads to the voluntary curtailment of expression by those who seek to avoid controversy… The arts cannot thrive in such a climate of fear.”

Religious extremism already makes it tenuous for artists to navigate the treacherous waters of artistic creation in Pakistan, and many practitioners who choose to dabble in controversial visuals and subject matter risk limited exposure at the least and threat to life at the most.

Incidents like these may stoke the fire within a few rebellious hearts but remind a large majority why it is simply not worth the trouble. What was only in the subtext and merely assumed in the past is now proven to be true, that no one is exempt, free speech is a myth, and artists who step out of line are not safe. Art is pushed further into the margins and peripheries.

This is clearly evidenced in the Karachi Biennale Trust’s response to the entire incident, which was to abandon the artists in the name of saving the biennale and bringing art into the mainstream discourse. Was it a sensible move to sacrifice the one to save the many, and to allow the show to go on for the benefit of the larger art community?

Or was it cowardice to throw a fellow artist under the bus in order to protect themselves? If only a certain type of art can remain in the centre, dictated by those with their own agendas and a narrow understanding of the standards of contemporary art, then what is even the point?

In the face of this dilemma, the inscription on Suleman’s memorial graveyard becomes even more pertinent:

“When confronted with violent terror we acquiesced, in the denial that the same beast of intolerance raged rampant within our own souls. Do you wonder why we lie before you, the countless un-mourned? We ourselves are the victim but also the perpetrator of this very terror.”

As the old adage goes, “Zulm sehna bhi zulm hai [Tolerating oppression is also oppression].” In our refusal to stand up in the face of oppression, we ourselves risk becoming the oppressors.

The writer is an independent art critic and curator

Published in Dawn, EOS, December 25th, 2022