The tragic allision of the container ship Dali with the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore is sure to produce a good deal of speculation as to causal and contributing factors, and the NTSB investigation will certainly provide specific insights when it is completed. One area that will certainly be of interest is the impact of fatigue on maritime operations.

Although not a sleep scientist, I am an experienced Mariner and Human Factors Engineer who studies fatigue for a living and assists in creation of policy for fatigue management and crew endurance for the United States Navy. In our training, one of the key areas that we focus on is the circadian clock, which is part of our human biology. In fact, looking back at historical precedents, the vast majority of significant maritime incidents involving loss of life occurred in the natural circadian dip between midnight and 4:00 am.

Having stood my share of midnight watches, I can attest that the combination of fatigue, darkness, confusing lights, and stress can definitely impact performance and decision making. My own close call occurred in 2002 while in command of USS Oscar Austin (DDG 79) during a strait transit under the Copenhagen Bridge. Having been up all day and into a night transit under the bridge, I dozed off at a critical moment. I opened my eyes as the panicked crew scrambled to figure out what was going on. It was quickly apparent everybody lost track of where we were . . . including me.

Out of caution I gave the order to stop the ship - and then I realized that I had no idea what was going on. I had forgotten that there were three ships behind me that could have run into me had not an alert watch stander announced on the Bridge to Bridge radio that I was stopping my engines. I was so tired that I didn’t think it through; in my foggy state, I could have driven us into shallow water (or into the bridge) or caused a multi-ship collision! Everything turned out OK, but in retrospect I let myself get so tired that I basically caused a near miss[i].

The author fell asleep while piloting the USS Oscar Austin in Denmark. This photo, published on www.navsource.org, was taken from one of the three ships following the vessel on the night of the near-miss. (Kevin Elliott / U.S. Navy photo)

After a series of fatal collisions in 2017, where fatigue was found by both Navy and the NTSB to be a contributing factor[ii], most of the Navy adopted a circadian watch rotation which takes into account the body’s natural cycle and places watch and sleep periods at the same time each day. According to most experts, the majority of the commercial maritime industry is a similar schedule, with four hours on watch followed by eight hours off. However, manning shortages, excessive workload and scheduling anomalies can create a situation where a circadian watch rotation is not enough to ward off excessive fatigue.

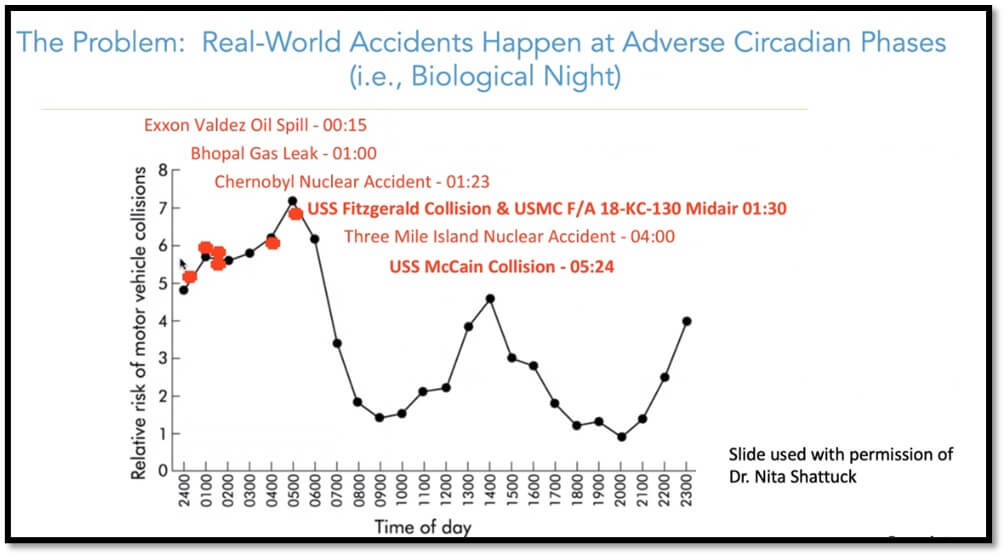

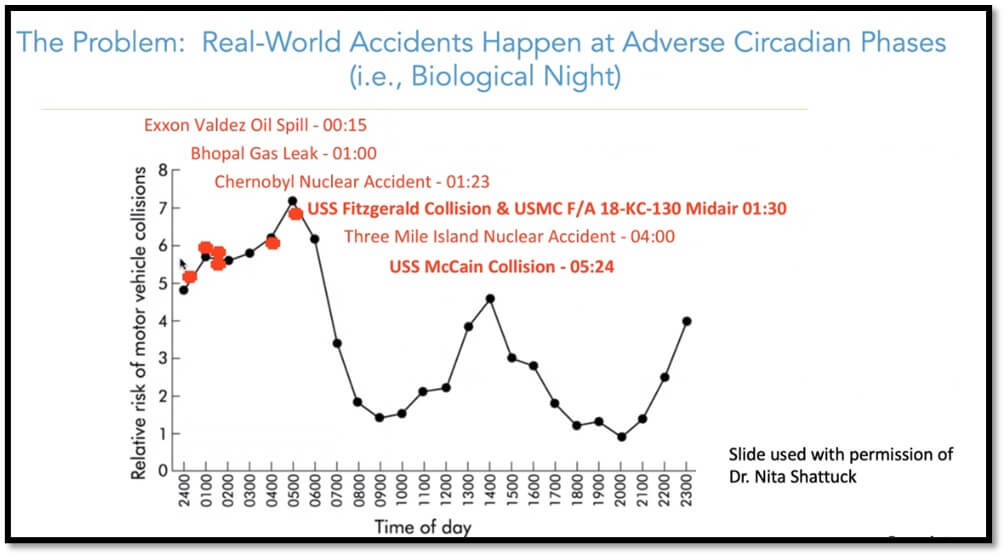

While it is too early to tell, historical precedent is fairly consistent. The following graph from my colleague at the Naval Postgraduate School, Dr. Nita Shattuck, shows a few key incidents and their location on the circadian cycle:

Figure 1. A study of ship collisions and other major incidents shows that the vast majority of them occur during the naturally adverse phase of the circadian rhythm where reactions are slower. MV Dali hit the Key Bridge at 01:29 AM (Courtesy of Dr. Nita Shattuck, Naval Postgraduate School.

A 2021 Cambridge study of over 1600 maritime collisions concluded that:

“The result of the analysis confirms that collisions between vessels are more frequent at night and that these accidents are usually more serious than during the daylight watches. This does not mean that bridge officers and lookouts are not affected by fatigue during sunlight shifts, but that the necessary absence of light to improve the vision during the night watches diminishes their skills. As a result, the probability of shipping accidents fluctuates according to a circadian rhythm with peaks during the night. Although this analysis has focused only on collisions, it should be accepted that it affects any kind of task carried out by watch keepers, which means that the results obtained in this investigation can be extrapolated to any type of navigation incidents.[iii]”

In the case of the MV Dali, however, the watchstanders appear to have had the presence of mind to announce an emergency situation with a “Mayday” call that quite likely saved lives, allowing authorities to stop traffic from crossing the bridge, but unfortunately not in enough time to warn the workers in their cars on break[iv]. Despite the historical precedent and personal examples cited in this article, it is entirely possible that the master and crew were taking preemptive measures to reduce nighttime fatigue in a close maneuvering situation, and that these practices paid dividends in a casualty situation – only time will tell.

Captain (retired) John Cordle completed two Navy surface ship command tours including a wartime deployment in command of USS Oscar Austin (DDG 79) and a counter-piracy deployment in command of USS San Jacinto (CG 56). He was awarded the Navy League John Paul Jones Award and the Bureau of Navy Medicine Epictetus Award for Innovative and Inspirational Leadership for his work in crew endurance and circadian watch rotations.

References:

[i] You Have To Close Your Eyes To See The Military's Powerful New Weapon, Sarah DiGiulio, Huffington Post, Jul 30, 2016

[ii] Comprehensive Review of Recent Surface Force Incidents, VADM R. Davidson, United States Navy, 28 October 2017

[iii] The effect of circadian rhythms on shipping accidents, Juan Vinagre-Ríos, José-Manuel Pérez-Canosa, and Santiago Iglesias-Baniela. Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 April 2021

[iv] What to know about the cargo ship Dali, a mid-sized ocean monster that took down a Baltimore bridge, Rick Perry, AP News, 28 March 2024

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.

Lou Conter, the last remaining survivor of the lost battleship USS Arizona, has passed away at the age of 102. He was one of 335 sailors who survived the Japanese strike on the warship during the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 - and just one of 93 survivors who had been on the ship.

Lou Conter, the last remaining survivor of the lost battleship USS Arizona, has passed away at the age of 102. He was one of 335 sailors who survived the Japanese strike on the warship during the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 - and just one of 93 survivors who had been on the ship.