Thomas Wintle

Is hydrogen the sleeping giant of European energy? If the European Commission's strategy to achieve climate neutrality is anything to go by, it could indeed be the fuel that drives the EU's Green Deal and the economic bloc into the 21st century.

But despite July's announcement of plans to boost hydrogen power to 14 percent of the bloc's energy mix by 2050, the gas has received relatively little public attention until recently.

So what exactly is hydrogen energy, how does it work, and what does it hold for the future?

Read more: EU energy plans prioritize hydrogen strategy

What is hydrogen energy and why is it green?

Hydrogen, much like batteries or combustion engines, has the potential to power pretty much anything: cars, steel production, household heating, even planes or everyday laptop.

"Potentially, it's an extremely versatile fuel," says Professor Paul Ekins, a specialist in environmentally sustainable economy formerly at University College London.

Hydrogen is typically generated with a fuel cell, a device that combines oxygen with hydrogen to generate electricity and heat. The only other direct byproduct from the fuel cell process is water, and this is what gives hydrogen the potential to be "clean fuel" - unlike burning fossil fuels, it doesn't produce any carbon emissions. In fact, according to the European Commission, clean hydrogen has the potential to reduce carbon emissions in European industries by 90 million tons per year by 2030.

While electric batteries also have low-carbon possibilities, the big difference is that hydrogen fuel cells do not run down as long as they are supplied with fuel. /Getty Creative / VCG

While electric batteries also have low-carbon possibilities, the big difference is that hydrogen fuel cells do not run down as long as they are supplied with fuel: "With a battery, you're always stuck with whatever charge you have onboard," says Professor Robert Steinberger-Wilckens, a fuel cell research specialist at Birmingham University:

"The owner of an iPhone will know that for whatever reasons, they're just always running out of battery and you have to recharge all the time. With hydrogen, you just have a small tank and that could last you anything between a day, five days, a month."

The other bonus is that there aren't any moving parts in a typical fuel cell, meaning they are more reliable in comparison to today's combustion engines and can operate in relative silence. On average, they are also 2.4 times more energy efficient than a standard diesel engine.

Watch: Researchers claim they've developed cheap and clean hydrogen fuel

How is hydrogen sourced and why is it a problem?

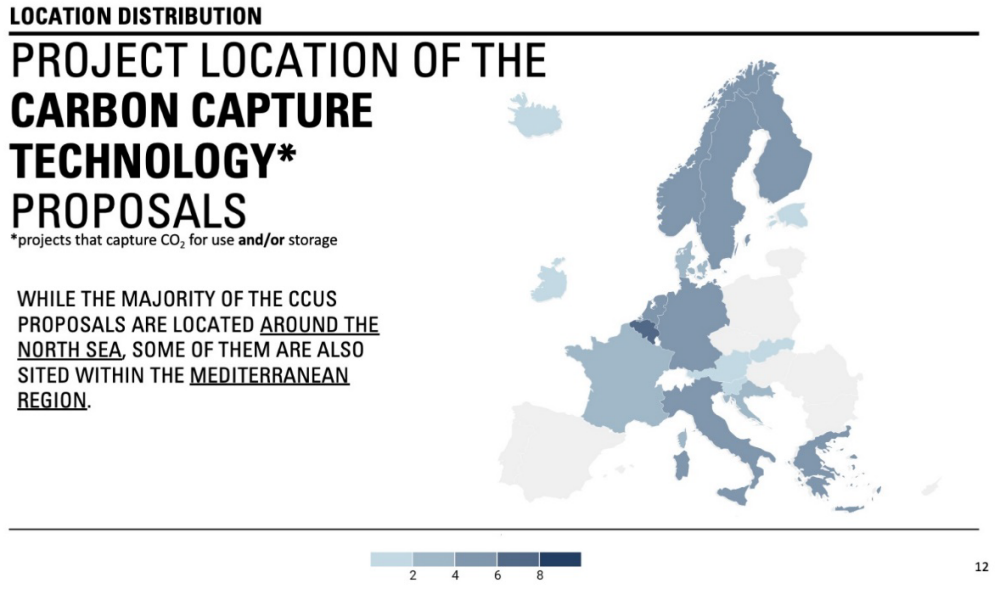

While fuel cells themselves don't produce carbon emissions, sourcing hydrogen can and often does. In the EU, where hydrogen currently accounts for 2 percent of the bloc's energy mix, it is produced almost exclusively from fossil fuels.

The most common production method separates hydrogen from natural gas and coal and accounts for the release of 70 to 100 million tonnes of carbon dioxide every year.

For Ekins, what is dubbed as "black hydrogen" production is "not at all a low carbon way of producing it because the carbon dioxide is not currently captured and stored."

Even if the CO2 were to be captured, - part of the EU's plans - this would mean storing it for thousands or tens of thousands of years: "Effectively, it has to be stored away forever," he says, "and forever is quite a long time."

VIDEO 03:36 Hydrogen power: the sleeping giant of clean energy? - CGTN

However, the process is currently much more expensive than processing natural gas and it still needs something to provide the electricity that powers it. Until electrolyzers can be run on renewable energy like wind and solar power on a mass scale, this means burning more fossil fuels.

Currently green hydrogen production accounts for one gigawatt of power in the EU, but the bloc is counting on the cost of electrolysis coming down dramatically in the next five years. On that basis, the Commission aims to roll out renewable hydrogen production facilities with a capacity of at least 6 gigawatts by 2024, and between 2025 and 2030, this will be expanded to 40 gigawatts.

But for the foreseeable future, hydrogen will likely be reliant on natural gas, prompting concern among environmentalists. European Parliament member Ville Niinisto warned the commission's hydrogen strategy "must not be allowed to become a green-washing exercise used to subsidize obsolete gas pipelines."

Tesla Inc CEO Elon Musk famously described fuel-cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) as "mind-bogglingly stupid." Aly Song/Reuters

How do fuel cell cars compare to electric battery vehicles?

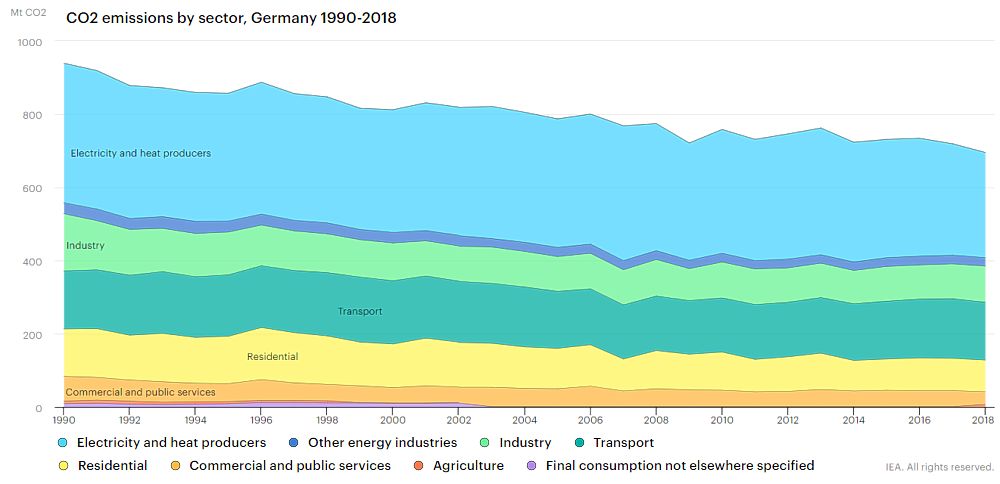

Concerns around production notwithstanding, the EU is banking on hydrogen power to achieve its net-zero emissions goal of 2050, particularly in the area of transport, which currently accounts for around 30 percent of the EU's total CO2 emissions.

But up until recently, the gas has largely been eclipsed in public discourse:

"We're currently always talking about hydrogen, which about five or six years ago in England, we were essentially not allowed to," says Steinberger-Wilckens: "Nobody wanted to hear anything about hydrogen."

This is in part because of the growing buzz around the use of electric batteries, especially in the mobility sector. But despite Elon Musk's famous statement that fuel-cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) are "mind-bogglingly stupid," there are many benefits to using hydrogen in cars over electric batteries.

Hydrogen-powered cars have a better range than battery powered vehicles, making average distances of 320-405km per hit of hydrogen, to a BEV's range of 160-500km. /Getty Creative / VCG

Both FCEVs and the battery-operated electric vehicles (BEVs) prized by manufacturers like Tesla have zero tail-pipe emissions, but the former are similar to petrol engines in that they are quick to refuel, taking a matter of minutes. In comparison, BEVs can take up to 12 hours to charge.

Hydrogen-powered cars also have a better range than battery powered vehicles, making average distances of 320-405km per hit of hydrogen, to a BEV's range of 160-500km. The main problem is that starting prices for FCEVs like Toyata's Mirai, released in late 2014, are almost three times higher than their electric counterparts.

Professor Ekins says that this is in part because electric vehicle technology has been around a lot longer, and that hydrogen is currently quite expensive.

"Certainly battery electric vehicles seem to have the edge," he says, in part because there is already an easily accessible electricity grid, but adds that it's possible we will see a mixture of these vehicles on the road in the future:

"Musk may be right, he may win the vehicle race, but it's not by any means a foregone conclusion."

Read more: Hydrogen vehicles to play major role in greening the auto industry

Currently green hydrogen production accounts for one gigawatt of power in the EU, but the European Commission aims to roll out renewable hydrogen production facilities with a capacity of at least 6 gigawatts by 2024. / Bim / Getty Creative / VCG

So where is hydrogen energy most applicable?

While the EU appears to be focusing more on battery powered vehicles for personal mobility, the advanced range and quick filling times of hydrogen fuel cells make them useful for vehicles that need to go far and don't have much down time.

That means public transport like local city buses and long-haul vehicles such as lorries, shipping, and even planes.

In China, where the government spent about $12.4 billion in 2018 on supporting the expansion of FCEVs, Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan province, has recently replaced its entire bus fleet with hydrogen models. In January, Wuhan inaugurated the country's first fleet of hydrogen powered commuter shuttle buses.

"One of the issues with hydrogen is that you need quite a large fuel tank in order to store enough so that you're not having to fill up all the time," says Ekins: "Therefore, these large applications may be more appropriate than trying to get a large hydrogen fuel tank at very high pressure into a rather small motor vehicle."

The advanced range and quick filling times of hydrogen fuel cells make them useful for vehicles that need to go far and don't have much down time likes buses. / oasis2me / Getty Creative / VCG

The EU also references the potential use of hydrogen to drive aviation, using liquid synthetic kerosene or other synthetic fuels made from hydrogen to power planes, solving the problem of electric batteries' short lifespan.

However, Ekins says there could be problems with this because concentrating hydrogen could create heavy tanks, where planes need to be light: "There's still a lot of uncertainty about how much hydrogen we're going to be using in the future."

One area where hydrogen definitely will be expanded in the EU is in carbon intensive industrial processes, particularly in areas like chemical, steel and cement production, where "black hydrogen" is already in use.

But hydrogen power has the potential to go much further. In 2021, Toyota will begin constructing Woven City – a prototype city for 2000 people in Japan powered almost exclusively by hydrogen fuel cells.

However, there is a big difference between rolling out hydrogen power for 2000 people and the EU's population of 445 million, and this hints at some of the problems the rollout of hydrogen energy faces.

Read more: China's installed capacity of hydrogen fuel cells soars sixfold in first seven months

What are the main hurdles in switching to hydrogen?

The first obstacle is the massive operation involved in switching energy infrastructures, with the relative newness of hydrogen power meaning the overhaul will cost much more.

The price tag for the EU's hydrogen plans over the next 30 years currently stands at between $203 and $530 billion, and amid a historic economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, critics will likely want to see the proposed funding slashed.

However, for Ekins, "any major change of fuel or energy source is going to have significant infrastructure implications," and will come up against opposition, particularly from those that currently profit from fossil fuel exports.

This hints at another problem: while the EU is promising to move towards 'green hydrogen', Professor Steinberger-Wilckens says there is little motivation for oil and gas companies to do so under the current strategy.

"They have zero incentives or a negative incentive to change to anything that is environmentally more benign," he adds, pointing out that firms are unlikely to discard their assets while hydrogen production continues to rely on fossil fuels.

"There are lots of misconceptions about how dangerous hydrogen is," says Professor Ekins: "Everyone always thinks of hydrogen airships, the Hindenburg disaster and all that kind of thing." /Wikicommons

This is particularly worrying when the European Clean Hydrogen Alliance, in charge of investment for the hydrogen projects under the commission's plans, is heavily represented by gas and carbon-heavy industry companies.

Finally, there is the difficulty in changing consumer behaviour and soothing public concerns about storing hydrogen, which is highly flammable.

"There are lots of misconceptions about how dangerous hydrogen is," says Ekins: "Everyone always thinks of hydrogen airships, the Hindenburg disaster and all that kind of thing."

He says that in in principle, hydrogen is much, much safer than petrol, in that if it does ignite, it explodes upwards, as opposed to outwards: "I'm absolutely certain that we could find ways of using hydrogen safely."

Read more: Commercialization remains challenging for hydrogen power in China

What do we stand to gain from making the switch?

If the EU is able to move away from reliance on natural gas production to source its hydrogen, and start creating its own through renewables, Ekins say that "Europe could become more or less energy independent."

With natural gas sources coming from countries like Russia, Ukraine, and the Balkan states, this will allow Europe to be essentially energy self-sustainable. This also means relative security for energy prices, as opposed to the fluctuations seen in the fossil fuel market.

And by diversifying the source of hydrogen production through localized renewables, Professor Steinberger-Wilckens says a new decentralized supply chain will be far more resilient than our current model.

"The different methods of obtaining hydrogen are so varied that you just have a much larger bandwidth of sources," he says: "You wouldn't necessarily have the large utilities owning everything. You would have more of a brokerage company pulling all these loose ends together."

By diversifying the source of hydrogen production through localized renewables, hydrogen could offer a new decentralized supply chain more resilient than our current model. /polesnoy / Getty Creative

However, he stresses that hydrogen power will not solve all ills: "We need to ramp up renewable energy input, but at the same time, we have to reduce energy demand."

He points to plans in the UK to replace natural gas with hydrogen instead, "which will lead nowhere because the energy efficiency standards of housing in the UK are just so tremendously bad."

He says instead energy use must be cut by some 70 percent through efficiency in houses and on roads, a figure he considers economically viable: "There's no point covering today's energy demand with something like renewable energies, and exactly the same applies to hydrogen."

If hydrogen power is to be economically viable in effectively lowering green house gases, Steinberger-Wilckens says there must be a rethinking of how we use fuel: "[hydrogen] has a different mindset altogether."

Video/animation: James Sandifer