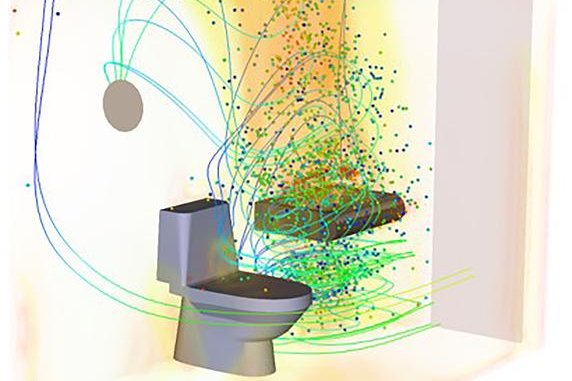

Recirculating flow in 'dead zones' in public restrooms can trap infectious particles for long periods, including those that spread COVID-19, according to a new study. Photo by Vivek Kumar/Ansys Inc.

Nov. 2 (UPI) -- Preventing airflow "dead zones" within indoor spaces may help prevent the spread of COVID-19 and other dangerous pathogens, an analysis published Tuesday by the journal Physics of Fluids found.

Computer simulations of airflow within a public restroom show that infectious aerosols in dead zones, where air does not flow, can linger up to 10 times longer than they do in other parts of the room, where air flows in and out, the data showed.

These dead zones of trapped air are frequently found in corners of a room or around furniture, the researchers said.

"Surprisingly, [dead zones] can be near a door or window, or right next to where an air conditioner is blowing in air," study co-author Krishnendu Sinha said in a press release.

"You might expect these to be safe zones, but they are not," said Sinha, a professor of aerospace engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay.

COVID-19 spreads primarily through the air, after virus droplets are emitted from infected people, research suggests.

This is particularly true in confined, crowded, indoor spaces -- including those with air conditioning and air purifying systems -- where air may not flow freely and virus particles may linger as a result.

These virus droplets or particles essentially float in the air in these spaces, where they can be inhaled by others and transmitted.

For this study, Sinha and his colleagues focused on public restrooms, which typically generate aerosols and are found in offices, restaurants, schools, planes, trains and other public spaces.

In particular, public restrooms have been identified as a potential source of infection transmission within densely populated areas in India, the researchers said.

RELATED In confined spaces, air purifiers may actually aid the spread of COVID-19

Ventilation design for public spaces is often based on air changes per hour, calculations that assume fresh air reaches every corner of a room uniformly.

However, "from computer simulations and experiments within a real washroom, we know this does not occur," Sinha said.

The researchers' computer simulations of air flow in one public restroom showed that air moves "in circuitous routes, like a vortex," co-author Vivek Kumar said in a press release.

Ideally, air should be continuously circulating in every part of the room and constantly replaced by fresh air, said Kumar, a student in bioengineering at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay.

This isn't easy to do when air is recirculating in a dead zone, however, where furniture or other structures may be inhibiting flow, the researchers said.

"ACH can be 10 times lower for dead zones," Sinha said.

"To design ventilation systems to be more effective against the virus, we need to place ducts and fans based on the air circulation within the room, [but] blindly increasing the volume of air through existing ducts will not solve the problem," he said.