The National Transportation Safety Board has released its report on the engine room fire aboard the Staten Island ferry Sandy Ground in 2022, which disabled the vessel in New York Harbor and caused $13 million in damage. The agency concluded that a design issue and a crewmember error caused the fuel oil system to exceed rated pressure, warping four fuel filter housings and spraying fuel oil onto a hot exhaust manifold.

On December 22, 2022, Sandy Ground was operating on her normal run between Manhattan and Staten Island, with all four main engines running. Four engineering crewmembers were on watch, including the chief engineer, an assistant engineer and two oilers. The fuel oil purifier was online and feeding clean fuel to the two day tanks in the engine room.

As the day tanks were off the centerline, the crew had a practice of keeping the levels about the same for reasons of stability, with about 2,000 gallons in each. As the afternoon wore on, the levels in the tanks began to differ and were about 500 gallons apart by 1600. In an attempt to even out the tank levels, the two oilers made multiple adjustments to the fuel oil service supply valve (on the service pipe from the tank to the engines) and the fuel oil return isolation valve (on the return line) on each of the two tanks. Their goal was to change the flow rates in and out of the tanks in order to bring the levels back into line, and they kept adjusting fuel system valves for about 40 minutes.

At 1647, a cascade of alarms sounded for all main engines, including high fuel pressure, low fuel pressure and check engine alarms. Fuel was leaking out of multiple spin-on filter assemblies, spraying the number two main engine's exhaust manifold and the number three and four main engines. The chief engineer called the wheelhouse and told the captain that the ferry would likely lose propulsion and steering.

The two oilers went into the engine room and attempted to contain the fuel spray by wrapping absorbent pads onto the spin-on filters, without success. At 1654, seven minutes after the first alarms sounded, a fire broke out on the exhaust manifold of the number two main engine and quickly spread. The ferry lost power and drifted to a stop, and the crew deployed anchor and made a distress call to the Coast Guard.

The engineering crew evacuated the engine room through an escape hatch, and when they were clear, the dampers were shut, ventilation was shut down, and the fuel oil cutoff valves were activated. With the captain's permission and the engine room fully sealed, the chief engineer remotely activated the fixed firefighting system, filling the space with extinguishing gas. The crew kept the hatches sealed, and the fire eventually went out.

Over the next hour, most of the passengers were evacuated onto smaller good Samaritan vessels. Tugs quickly took the ferry under tow and it was moored at the St. George terminal in Staten Island by 1825. No injuries were reported, though two crewmembers were treated for smoke inhalation.

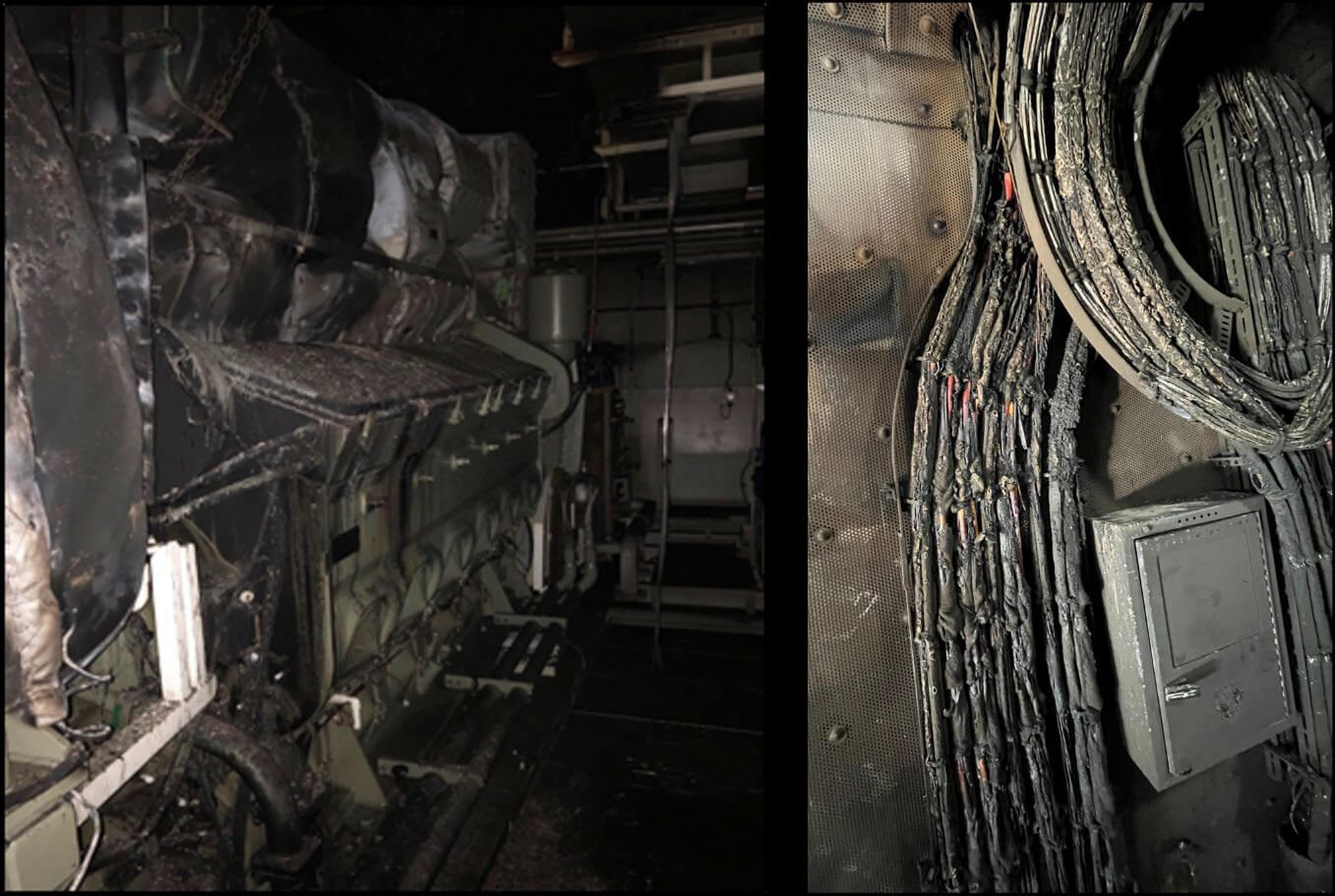

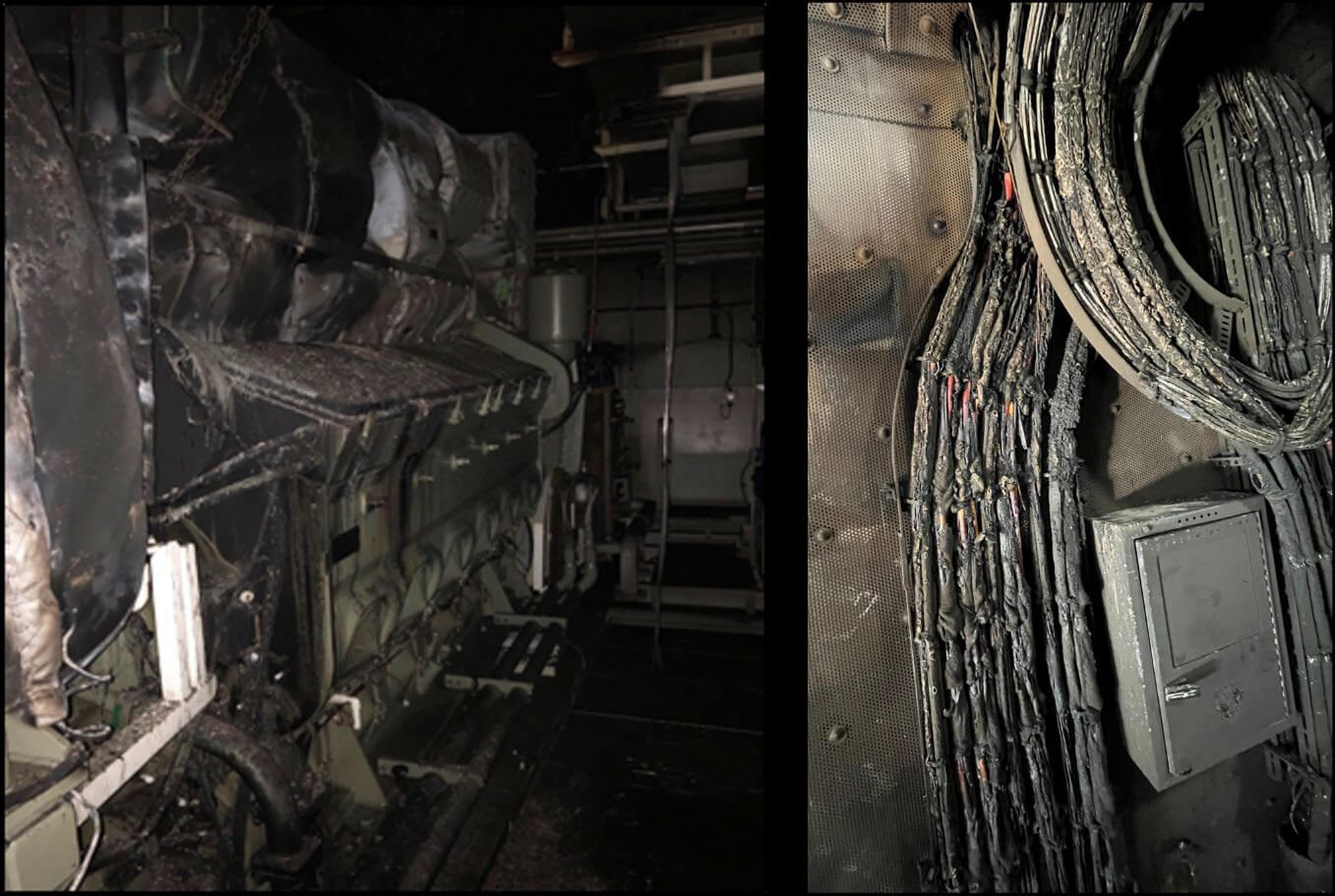

Fire and smoke damage to the number two main engine and to a bundle of cabling (NTSB)

Fire and smoke damage to the number two main engine and to a bundle of cabling (NTSB)

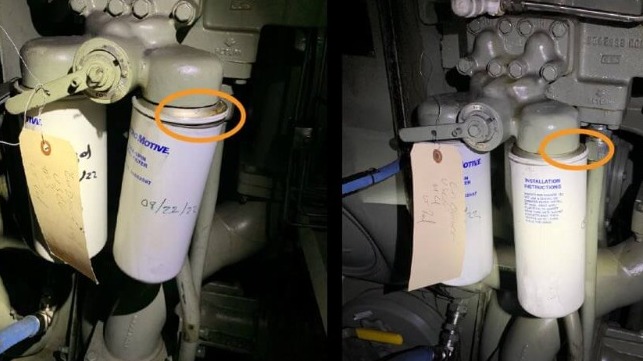

Once the engine room was cleared for safe entry, a task force of federal investigators, technicians and ferry service personnel entered and examined the compartment. They found that the spin-on filter housings on all four main engines were distorted, and the gasket on one filter had blown out in the direction of the number two main engine, allowing fuel to spray out and hit the exhaust manifold.

Investigators' attention turned to the fuel oil return isolation valve for each tank. These two ball valves appeared in the pre-contract drawings for the vessel's design, but were not installed at the shipyard.

After delivery, and after the crewmembers had completed training on the new ferry, these valves were retrofitted onto the fuel system at the operator's request, conforming to the pre-contract design drawings. Critically, the design and the retrofit did not include a pressure relief valve on the return line, NTSB said. The ferries that the engineering crewmembers had worked on previously in their careers (the Molinari- and Barberi-class) all had relief valves and could not be accidentally overpressurized if the isolation valves were closed.

NTSB concluded that the two oilers "likely did not fully understand how the system functioned," and that they shut off both return valves at the same time in the moments before the casualty. Since there was no relief valve in the fuel return system design, this left the return line from all four main engines with nowhere to go. Pressure in the fuel supply system immediately spiked above the maximum sensor limit (148 PSI) in every engine, damaging all four spin-on filter housings and initiating the fuel spray.

"The only possible scenario that could have led to the overpressurization was the complete closure of the fuel oil return isolation ball valves to both fuel oil day tanks, which would have prevented any return fuel oil from flowing freely into either of the fuel oil day tanks," NTSB found. "Had the Sandy Ground fuel oil system been equipped with [a] pressure relief valve installed in the fuel oil return line . . . a fuel oil system overpressurization would have been prevented."

There are no regulations requiring relief valves on the return line, and their use is voluntary (though encouraged by SNAME and by the engine OEM). Both class and the Coast Guard reviewed and approved the pre-contract design drawings, which were technically compliant.

NTSB recommended that IACS, class and the Coast Guard should add a relief valve requirement for any return line from a positive-displacement fuel pump, like those aboard Sandy Ground.

Sandy Ground's fuel return lines were equipped with new relief valves during repairs. The operator plans to retrofit relief valves onto other ferries in the class during shipyard availabilities.

Fire and smoke damage to the number two main engine and to a bundle of cabling (NTSB)

Fire and smoke damage to the number two main engine and to a bundle of cabling (NTSB)