Why don’t Labour’s workers’ and renters’ rights reforms cut through to voters – and how should they?

When millions of workers and renters don’t know you’re doing more to improve their rights than any government in half a century, something is going very badly wrong.

“No-one who would benefit in my area knows about them,” vents one Labour MP, despite their leafleting blitz.

Recent polling bears this out. Almost half the public hadn’t heard much or anything about either reforms, including two in five Labour voters.

Deliverism is dead. Long live deliverism?

The problem isn’t Number 10 assuming policy delivery alone wins votes. Joe Biden’s defeat despite impressive achievements put paid to that, with Morgan McSweeney reportedly circulating papers on the “death of deliverism” within days of Labour’s landslide.

So why aren’t even life-changing, flagship policies cutting through, and what can Labour do?

LabourList asked a string of MPs and communication, polling and policy experts within and beyond Labour. Their analysis boiled down to three areas – messaging itself, how it’s told, and the messengers.

Stories need heroes and villains

The first messaging idea is simple: stop avoiding conflict. Be the “insurgent” government McSweeney also spoke of last July.

“The government hasn’t sought enemies on workers’ and renters’ rights, perhaps nervous about upsetting particular stakeholders,” says Steve Akehurst of Persuasion UK.

But conflict means attention. “Winter fuel and welfare were big fights. Stories that hang around have protagonists and antagonists.”

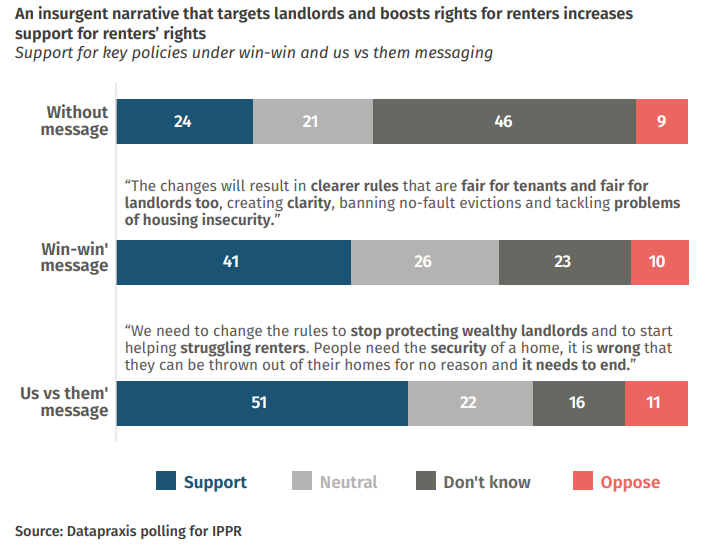

Akehurt’s recent report with the IPPR surveyed voters on a “Labour vs corporate interests” message, and found three times more support than opposition.

Framing rental reforms as a win for tenants and landlords boosted support, but framing them as helping tenants over landlords boosted it far more:

Akehurst suggests talking more openly about “transferring power” from landlords and employers would unite Reform – and Green –tempted Labour voters alike.

Defining itself more against opponents would help set the all-important “meta-narrative” about what the government is, he adds, and move debate off trickier Labour subjects like immigration.

Two MPs argue greater awareness would help prevent rival parties defining the employment debate too, and misinformation spreading. One even suggests picking a fight with Mike Ashley.

Don’t worry about losing landlords

Broadcaster, peer and ex-adviser Ayesha Hazarika is similarly sceptical of “doing good by stealth”, arguing Labour could have made more of renters’ reforms becoming law last week. “It makes you look timid – you’ve got to own good, Labour legislation you’ve delivered quickly.”

Tom Darling of the Renters’ Reform Coalition agrees government has seemed “sheepish” looking progressive.

Reticence could explain why Ipsos polling recently found voters are “less likely to have heard of the policies they like most”.

Darling was positive about more recent government messaging on renters however, and others praised one MP’s leaning into the backlash:

Several party figures note landlords probably won’t vote Labour.

Even an ex-Tony Blair aide argues: “Landlords have the homes; we have the numbers. Renters and workers are clearly part of a bigger progressive coalition.”

John McTernan adds: “So we should tell them what they get from this, and do things in line with core and brand values. Is our name the bosses’ party?”

Farage shows voters want radicalism

Moderates would argue an anti-business image has cost Labour elections before.

But McTernan argues Brexit and the past three elections reflect one story: public demand for change.

Opinion data bears out the idea voters want “bolder changes”, according to Karin Christiansen of progressive analytics firm DataPraxis (and LabourList chair). “At European or even global level, the Overton window is the biggest in a long time, but often it’s the hard right stepping into it.”

One MP agrees. “If Nigel Farage shows one thing, it’s people want you to be radical.”

Voters only hear it when hacks tire of it

If us-versus-them is the message, how do you sell it? Through repetition, most interviewees agree, with a widespread frustration policies aren’t promoted more after their allocated day in the government’s news grid.

As former Keir Starmer adviser Peter Hyman recently warned of the case for ID cards, “people have to hear something at least five times…for it to stick”.

READ MORE: McKee on TikTok, authenticity and why Labour must catch up online

Announcements have to “breathe”, according to Hannah O’Rourke of campaign experts Campaign Lab, and fit into “patterns or rhythms”.

It’s less about simply voicing an often-demanded “grand narrative”, but instead showing it through more, smaller stories that are “way more persuasive and important”.

One former senior insider says comms teams need to know the broader “arc of the argument over the year”, fitting announcements into it.

How to skin the cat and nail social videos

Can a repeated, positive message land, though? Harlow MP Chris Vince notes some media cover “the bad things, not the good things”. News outlets naturally shun old news. One ex-insider is unsurprised “listicle” storytelling, reeling off policies and benefits, doesn’t cut through.

Yet Hazarika argues journalist are more “open-minded” covering policy post-announcement than sometimes assumed, if policymakers bring ideas – like exclusive coverage of a housing roundtable if one had been convened last week. Others suggest platforming voters on how they’ll benefit.

Christiansen says the centre left “have the solutions, if we’re a bit more brave and creative”. She also notes traditional media’s reach has “seriously contracted”.

With a third of young people getting news via TikTok, McTernan asks: “What’s the TikTok strategy to tell young workers and renters their rights?”

Many interviewees argue social media video is now king, and the secret is authentic storytelling, actual engagement with voters, and explainer videos.

Zohran Mamdani meets real people in viral videos to “bring it to life”, McTernan notes, and Hazarika acknowledges Robert Jenrick’s success “creating his own content”.

Several praise viral explainer videos by MP Gordon McKee, and first-person TUC clips like an EV factory worker asking: “Why does Nigel Farage want me to lose my job?”

Shoot the right messenger

Such clips highlight a third key point for video and wider cut-through – shoot the right messenger. While Hyman argues Starmer could do more “unfiltered” videos, others say varied messengers like trade union and rent campaign voices, Labour’s diverse new intake and community groups must be central, not optional.

Voters will trust union reps and community figures like London MP Margaret Mullane “more than they’re going to trust Keir Starmer,” says political commentator Andy Twelves.

Messengers must be “close to the people we’re trying to persuade” as public trust in politicians falls, adds O’Rourke.

Labour writer Paul Richards notes the significant online cut-through of right-wing “outriders” beyond Westminster, with too few credible Labour champions.

Delivery alone can’t deliver votes

Most interviewees agree cut-through is incredibly difficult, however. Richards notes complex reforms take time and leave a “credibility gap” beforehand, worsened by current “baked-in cynicism about government ability to change things”.

Even post-implementation, change may be noticed only when tenants encounter work or tenancy problems. “I hope people will see it, but it’s probably not a light switch moment,” says Vince. Elections abroad suggest benefiting voters don’t necessarily credit politicians, either – making relentless credit-taking vital, too.

A messaging reset clearly carries risks, from new enemies’ anger to voters cringing.

But as one MP says of the polls: “As it stands we’ve lost the next election, so what have we got to lose?”