By Kevin Liptak, CNN

Updated 8:02 PM ET, Tue July 28, 2020

Trump walks out of briefing after CNN question

(CNN)Even amid an attempt by President Donald Trump's aides to shift his focus back to coronavirus, he continues to hear from a wide range of associates -- including the CEO of a far-right television network -- who are undermining the administration's health experts and questioning their approach to the pandemic, people familiar with the conversations say.

Trump resumed his daily news briefings on Tuesday afternoon, where he again touted advancements on vaccines and treatments for the virus. After largely ignoring the pandemic for weeks and denying its severity, the White House revived the briefings last week to demonstrate presidential leadership.

But the approach has hit early stumbling blocks.

When Trump was pressed by CNN's Kaitlan Collins about his words of support for a doctor who downplayed masks and suggested alien DNA was used in medical treatments, he cut the briefing short and stormed out.

It was a sign that despite the efforts of his aides to recalibrate his approach, his own desire to improve his standing and the pandemic raging throughout the country, Trump is still trapped in some of the self-destructive tendencies that have brought him low.

While the President and Dr. Anthony Fauci are speaking again after going more than a month without meeting, Trump continues to hear from outside allies and even some inside the administration who have offered him competing advice and sometimes bad information, worrying some of his advisers who had once hoped to turn a page in the coronavirus response.

Trump also continues to hear steady criticism of Fauci, who has resumed making television appearances after weeks off the national airwaves -- earning him more irritation from the President, according to the people familiar.

Trump declared his relationship with Fauci is "very good" on Tuesday, but wondered why the doctor's approval rating is so high when his is so low.

"He's got this high approval rating. So why don't I have a high approval rating with respect -- and the administration -- with respect to the virus?" the President asked. "We should have it very high."

"It can only be my personality, that's all," he concluded.

The competing voices spilled into public view when Trump retweeted a message late Monday critical of Fauci that claimed the infectious disease expert had "misled the American public on many issues."

Fauci appeared hours later on ABC to say he would continue doing his job, despite the President's attacks.

A series of events earlier on Monday illustrated the dueling stream of voices influencing Trump as the outbreak continues to rage across the nation.

Midday, Fauci and others gathered in the Oval Office to update Trump on the 30,000-person Phase 3 trial launched by Moderna. Trump later told reporters it was a "great meeting" and participants walked away believing the President was sincere in his efforts to convey more leadership on the outbreak.

"We had a lot of our wonderful doctors and researchers with me," Trump said. "I think the meeting went really well."

While the meeting focused almost exclusively on the vaccine trial, and not on Trump's response to the virus more broadly, it seemed to participants like the President was engaged -- unlike some previous meetings that became derailed with unrelated topics and complaints.

But as the day progressed, Trump heard from several others who reinforced a different message than the one being offered by the administration's health experts. His hawkish trade adviser Peter Navarro -- who recently published an op-ed in USA Today trashing Fauci without running it past the White House but was never formally reprimanded -- traveled alongside Trump to North Carolina, where the President broke with health experts by calling on governors to reopen.

"I really do believe a lot of the governors should be opening up states that they're not opening," Trump said, countering the advice being offered by Fauci and Dr. Deborah Birx for states to rethink how they are lifting restrictions.

The same day, Trump spoke with Robert Herring, the chief executive of far-right OANN, about an unproven anti-malarial that Trump has long touted and even took himself, despite a lack of clear evidence on its efficacy in preventing or treating Covid.

"Yesterday, I had a chance to talk to President Trump about hydroxychloroquine," Herring later wrote on Twitter. "I gave him a list of doctors we have interviewed. I know he wants to help & put people back to work. Hope he talks to real doctors & not Dr. 'Farci.' "

Trump has cited OANN as a new favorite television channel after becoming frustrated with Fox News' willingness to interview Democrats. The channel, which is not distributed widely, often peddles wild conspiracies and false information.

By Monday evening, Trump had taken the hydroxychloroquine message public, retweeting a series of videos that were later removed by Twitter for containing false and misleading information about mask-wearing and the unproven drug.

Trump defended the video and the doctor it featured on Tuesday: "There was a woman who was spectacular in her statements about it and she's had tremendous success with it. And they took her voice off," he said.

But he seemed to back off when pressed about the statements made in the video itself, including that "you don't need masks" and the doctor's past statements about alien DNA used in medical treatments.

"I thought her voice was an important voice, but I know nothing about her," Trump said before abruptly departing the briefing room.

Fauci said on ABC he agrees with the Food and Drug Administration that "the overwhelming prevailing clinical trials that have looked at the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine have indicated that it is not effective in coronavirus disease."

The mild rebuke from Fauci caused some Trump advisers to shake their heads, fearing another round of headlines pitting Trump against the well-respected disease expert.

Last week, Trump said Fauci was a "nice guy" in an interview before his interviewer, Dave Portnoy of Barstool Sports, said the doctor was "on my ax list because every time he talks and says the country should stay inside, my stocks tank."

"Well, he'd like to see it closed up for a couple of years, but that's OK because I'm President, so I say, 'Well, I appreciate your opinion. Now give me another opinion, somebody please,' " Trump responded.

Meanwhile, Navarro has sustained his attacks on Fauci, saying he doesn't regret his unsanctioned op-ed and dinging the doctor for his wild first pitch last week at Nationals Park.

Asked by reporters at the White House on Tuesday about the continued attacks on Fauci, Navarro stormed away.

This story and headline have been updated with further news developments.

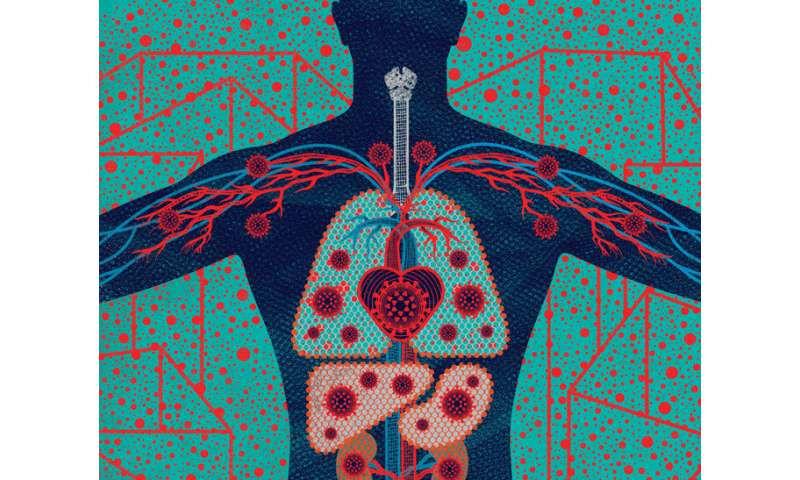

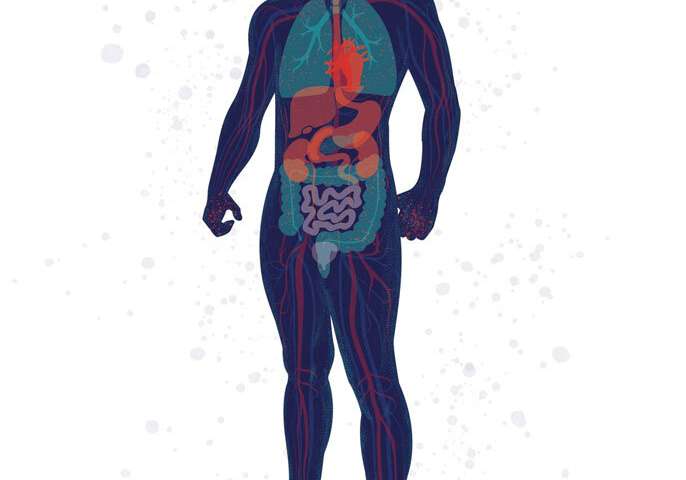

From Head to “COVID Toes”: People with COVID-19 exhibit from none to many of these symptoms. Some symptoms (such as fever, cough, and loss of smell) are common, while others (such as sore throat, pink eye, and stroke) are rare. Credit: Illustration: Stephanie Koch. Concept: Jennifer Babik, M.D., Ph.D.

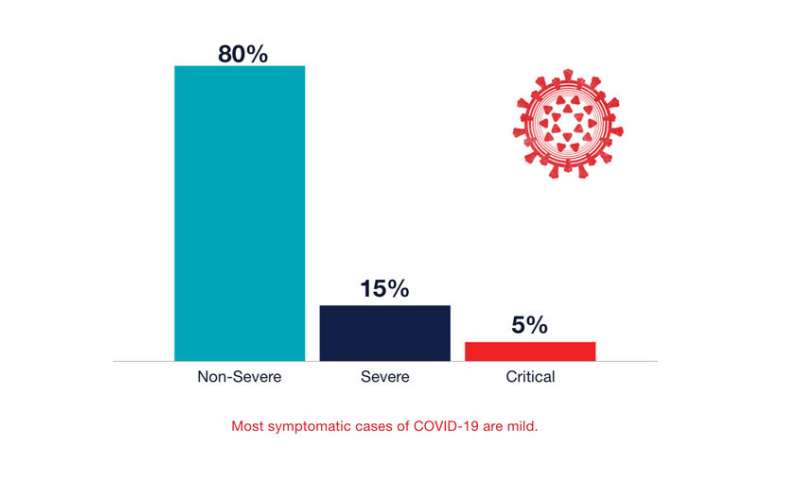

From Head to “COVID Toes”: People with COVID-19 exhibit from none to many of these symptoms. Some symptoms (such as fever, cough, and loss of smell) are common, while others (such as sore throat, pink eye, and stroke) are rare. Credit: Illustration: Stephanie Koch. Concept: Jennifer Babik, M.D., Ph.D. Most symptomatic cases of COVID-19 are mild. Credit: UCSF

Most symptomatic cases of COVID-19 are mild. Credit: UCSF