The WFP's biggest donor, the United States, has slashed its foreign aid under President Donald Trump

Reuters – A surge in militant attacks and instability in northern Nigeria is driving hunger to record levels, the UN World Food Programme (WFP) said on Tuesday, warning that nearly 35 million people could go hungry in 2026 as it runs out of resources in December.

Issued on: 25/11/2025 - RFI

By:RFIFollow

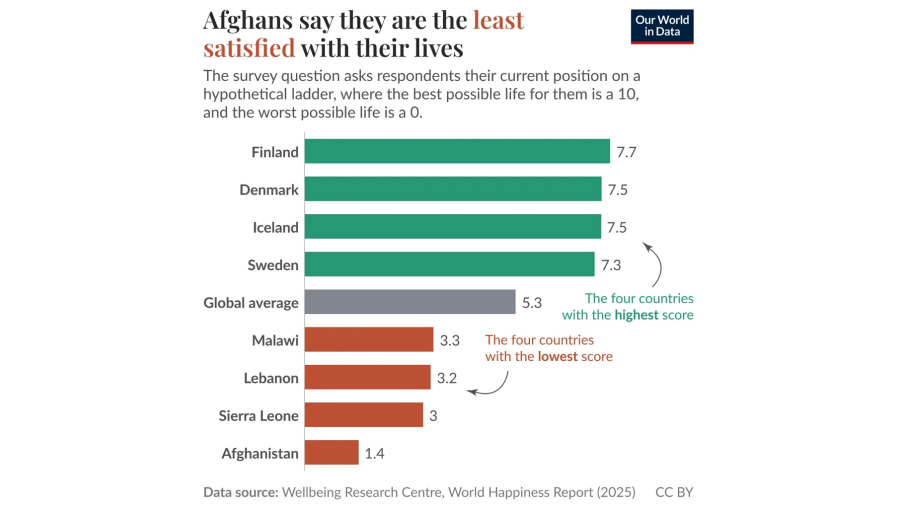

The projection, based on the latest Cadre Harmonisé – an analysis of acute food and nutrition insecurity in the Sahel and West Africa region, is the highest number recorded in Nigeria since monitoring began, the WFP said.

Violence has escalated in 2025, with attacks by insurgents including al-Qaeda affiliate Jama'at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), which carried out its first strike in Nigeria last month, and Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP).

Recent incidents underscore the crisis: ISWAP fighters killed a brigadier-general in the northeast, while armed bandits abducted more than 300 Catholic school students in a mass kidnapping days after storming a public school, killing a deputy head teacher and seizing 25 schoolgirls.

'Repeated attacks'

“The advance of insurgency presents a serious threat to stability in the north, with consequences reaching beyond Nigeria,” said David Stevenson, WFP Nigeria country director.

“Communities are under severe pressure from repeated attacks and economic stress.”

Rural farming communities have been hit hardest. Nearly 6 million people lack basic minimum food supplies in Borno, Adamawa and Yobe states, while 15,000 in Borno are projected to face famine-like conditions.

Malnutrition rates are highest among children in Borno, Sokoto, Yobe and Zamfara, WFP said.

Almost a million people in the northeast currently rely on WFP aid, but funding shortfalls forced the agency to scale down nutrition programmes in July, affecting more than 300,000 children.

In areas where clinics closed, malnutrition worsened from “serious” to “critical” in the third quarter.

The WFP's biggest donor, the United States, has slashed its foreign aid under President Donald Trump, and other major nations have also made or announced cuts in assistance.

WFP warned it will run out of funds for emergency food and nutrition aid by December, leaving millions dependent on its support without assistance in 2026.

WASHINGTON (AP) — The Republican president has kept up the pressure as Nigeria faced a series of attacks on schools and churches in violence that experts and residents say targets both Christians and Muslims.

Ope Adetayo, Sam Metz and Ben Finley

November 24, 2025

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Donald Trump’s administration is promoting efforts to work with Nigeria’s government to counter violence against Christians, signaling a broader strategy since he ordered preparations for possible military action and warned that the United States could go in “guns-a-blazing” to wipe out Islamic militants.

A State Department official said this past week that plans involve much more than just the potential use of military force, describing an expansive approach that includes diplomatic tools, such as potential sanctions, but also assistance programs and intelligence sharing with the Nigerian government.

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth also met with Nigeria’s national security adviser to discuss ways to stop the violence, posting photos on social media of the two of them shaking hands and smiling. It contrasted with Trump’s threats this month to stop all assistance to Nigeria if its government “continues to allow the killing of Christians.”

The efforts may support Trump’s pledge to avoid more involvement in foreign conflicts and come as the U.S. security footprint has diminished in Africa, where military partnerships have either been scaled down or canceled. American forces likely would have to be drawn from other parts of the world for any military intervention in Nigeria.

Still, the Republican president has kept up the pressure as Nigeria faced a series of attacks on schools and churches in violence that experts and residents say targets both Christians and Muslims.

“I’m really angry about it,” the president said Friday when asked about the new violence on the “Brian Kilmeade Show” on Fox News Radio. He alleged that Nigeria’s government has “done nothing” and said “what’s happening in Nigeria is a disgrace.”

The Nigerian government has rejected his claims.

A comprehensive approach

Following his meeting Thursday with Nigerian national security adviser Mallam Nuhu Ribadu, Hegseth on Friday posted on social media that the Pentagon is “working aggressively with Nigeria to end the persecution of Christians by jihadist terrorists.”

“Hegseth emphasized the need for Nigeria to demonstrate commitment and take both urgent and enduring action to stop violence against Christians and conveyed the Department’s desire to work by, with, and through Nigeria to deter and degrade terrorists that threaten the United States,” the Pentagon said in a statement.

Jonathan Pratt, who leads the State Department’s Bureau of African Affairs, told lawmakers Thursday that “possible Department of War engagement” is part of the larger plan, while the issue has been discussed by the National Security Council, an arm of the White House that advises the president on national security and foreign policy.

But Pratt described a wide-ranging approach at a congressional hearing about Trump’s recent designation of Nigeria as “a country of particular concern” over religious freedom, which opens the door for sanctions.

“This would span from security to policing to economic,” he said. “We want to look at all of these tools and have a comprehensive strategy to get the best result possible.”

Nigeria’s violence ‘will not be reversed overnight’

The violence in Nigeria is far more complex than Trump has portrayed, with militant Islamist groups like Boko Haram killing both Christians and Muslims. At the same time, mainly Muslim herders and mostly Christian farmers have been fighting over land and water. Armed bandits who are motivated more by money than religion also are carrying out abductions for ransom, with schools being a popular target.

In two mass abductions at schools this past week, students were kidnapped from a Catholic school Friday and others taken days earlier from a school in a Muslim-majority town. In a separate attack, gunmen killed two people at a church and abducted several worshippers.

The situation has drawn increasing global attention. Rapper Nicki Minaj spoke at a U.N. event organized by the U.S., saying “no group should ever be persecuted for practicing their religion.”

If the Trump administration did decide to organize an intervention, the departure of U.S. forces from neighboring Niger and their forced eviction from a French base near Chad’s capital last year have left fewer resources in the region.

Options include mobilizing resources from far-flung Djibouti in the Horn of Africa and from smaller, temporary hubs known as cooperative security locations. U.S. forces are operating in those places for specific missions, in conjunction with countries such as Ghana and Senegal, and likely aren’t big enough for an operation in Nigeria.

The region also has become a diplomatic black hole following a series of coups that rocked West Africa, leading military juntas to push out former Western partners. In Mali, senior American officials are now trying to reengage the junta.

Even if the U.S. military redirects forces and assets to strike inside Nigeria, some experts question how effective military action would be.

Judd Devermont, a senior adviser of the Africa program for the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said if Trump orders a few performative airstrikes, they would likely fail to degrade the Islamic militants who have been killing Christians and Muslims alike.

“Nigeria’s struggles with insecurity are decades in the making,” said Devermont, who was senior director for African affairs at the National Security Council under Democratic President Joe Biden. “It will not be reversed overnight by an influx of U.S. resources.”

Addressing the violence would require programs such as economic and interfaith partnerships as well as more robust policing, Devermont said, adding that U.S. involvement would require Nigeria’s cooperation.

“This is not a policy of neglect by the Nigerian government — it’s a problem of capacity,” Devermont said. “The federal government does not want to see its citizens being killed by Boko Haram and doesn’t want to see sectarian violence spiral out the way it has.”

US intervention carries risk

The Nigerian government rejected unilateral military intervention but said it welcomes help fighting armed groups.

Boko Haram and its splinter group, Islamic State of West Africa Province, have been waging a devastating Islamist insurgency in the northeastern region and the Lake Chad region, Africa’s largest basin. Militants often crisscross the lake on fast-moving boats, spilling the crisis into border countries like Chad, Cameroon and Niger.

U.S. intervention without coordinating with the Nigerian government would carry enormous danger.

“The consequences are that if the U.S deploys troops on the ground without understanding the context they are in, it poses risks to the troops,” said Malik Samuel, a security researcher at Good Governance Africa.

Nigeria’s own aerial assaults on armed groups have routinely resulted in accidental airstrikes that have killed civilians.

To get targeting right, the governments need a clear picture of the overlapping causes of farmer-herder conflict and banditry in border areas. Misreading the situation could send violence spilling over into neighboring countries, Samuel added.

___

Adetayo reported from Lagos, Nigeria, and Metz from Rabat, Morocco.

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

ABUJA, Nigeria (AP) — School kidnappings have come to define insecurity in Africa’s most populous nation, and analysts say it's often because armed gangs see schools as “strategic” targets to draw more attention.

Associated Press

November 24, 2025

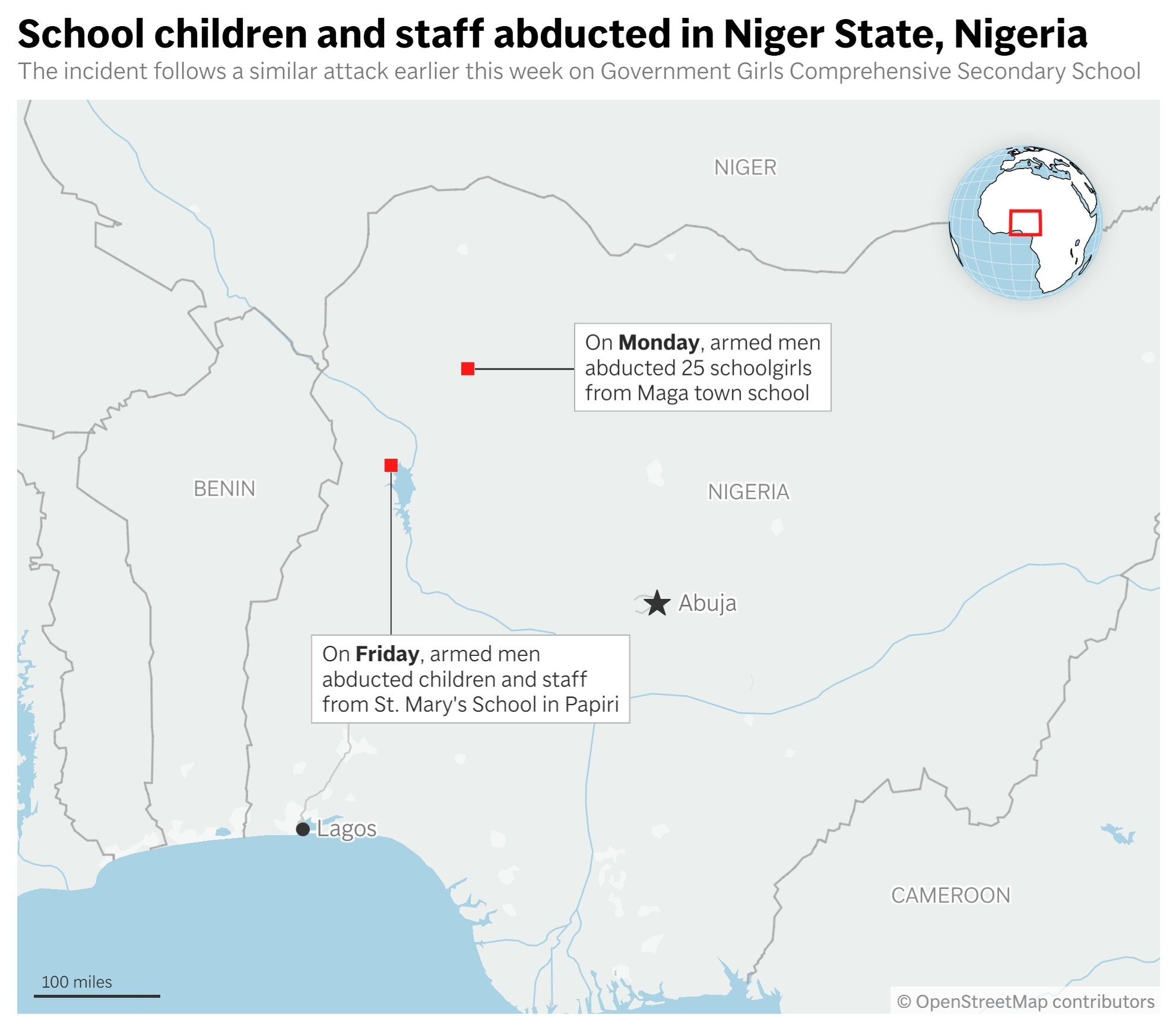

ABUJA, Nigeria (AP) — Nigeria suffered its second mass school abduction this week with authorities confirming an attack on a Catholic school in the conflict-battered northern region of the country on Friday.

A total of 303 schoolchildren and 12 teachers were abducted in Friday’s attack at St. Mary’s School in Niger state’s Papiri community. It wasn’t immediately confirmed who the attackers were. Local police said they have deployed a team to rescue the children.

Friday’s attack happened four days after 25 students were abducted in neighboring Kebbi state.

Niger state closed all its schools following the latest abduction.

School kidnappings have come to define insecurity in Africa’s most populous nation, and analysts say it’s often because armed gangs see schools as “strategic” targets to draw more attention.

UNICEF said last year that only 37% of schools across 10 of the conflict-hit states have early warning systems to detect threats.

The kidnappings are happening amid U.S. President Donald Trump’s claims of targeted killings against Christians in the West African country. Attacks in Nigeria affect both Christians and Muslims. The school attack earlier this week in Kebbi state was in the Muslim-majority Maga town.

Kidnappers in the past have included Boko Haram, a jihadi insurgency that carried out the mass abduction of 276 Chibok schoolgirls more than a decade ago, bringing the Islamic extremist group to global attention.

But dozens of bandit groups have become active in the hard-hit northern region, often targeting remote villages with a limited security and government presence.

At least 1,500 students have been seized in the years since the Chibok attack, many released only after ransoms were paid.

Here’s what’s to know about northern Nigeria’s widespread insecurity.

Boko Haram and an Islamic State affiliate

Boko Haram has long menaced large parts of Nigeria’s north, especially the northeast, as well as parts of neighboring Cameroon, Niger and Chad. The militant group has sought to impose an Islamic state in the region and its name — meaning “books are forbidden” — rejects Western education.

In 2014, Boko Haram burst onto the global stage with the Chibok abduction. Four years later, its fighters abducted 110 schoolgirls from a college in Yobe state in the northeast.

The militants have mounted a strong resurgence this year after splitting in the past, with many fighters now aligned with a local affiliate of the Islamic State group. The exact number of fighters with each group is unknown, though they are estimated in the low thousands.

The groups continue to recruit, sometimes forcibly, youth who have been left vulnerable in a region that Nigerian authorities and humanitarian organizations struggle to serve safely. The Trump administration’s deep cuts in foreign aid to Nigeria this year haven’t helped.

Abductions for ransom

Other armed groups in northern Nigeria carry out abductions, largely for ransom. Authorities have said they include mostly former herders who took up arms against farming communities after clashes between them over increasingly strained resources.

Schools have been a popular target of the bandits, who are motivated more by money than religious beliefs. The attacks often occur at night, with gunmen at times zooming in on motorbikes or even dressed in military uniforms and then disappearing into the vast, under-policed landscape.

There is growing concern about links between the bandits and the militant groups, notably in the northwest.

“While often conflated with the militant Islamist groups, the bandits operating in northwestern Nigeria are a distinct driver of instability in this region,” the U.S.-backed Africa Center for Strategic Studies said earlier this year, noting that the bandits are thought to be responsible for about the same number of deaths there as Boko Haram and the IS affiliate are in the northeast.

In 2020, gunmen on motorcycles attacked a government secondary school in Katsina state and abducted more than 300 boys. The state government announced their release within a week. In 2021, gunmen abducted more than 300 schoolgirls in a nighttime raid on a government secondary boarding school in Zamfara state. Within weeks, all were released after the apparent payment of a ransom.

And in 2024, gunmen on motorcycles abducted 287 students at a government secondary school in Kaduna state.

Nigeria’s security challenges

Nigeria has struggled for years to combat Boko Haram and other armed groups, at times striking and killing civilians in mistaken air assaults meant for militants. The military also has carried out airstrikes and special operations targeting the hideouts of armed gangs.

But Islamic extremists in recent months have repeatedly overrun military outposts, mined roads with bombs and raided civilian communities despite the military’s claims of success against them. That surge in activity has strained security efforts across Nigeria’s north.

Last month, President Bola Tinubu replaced the country’s security chiefs.

Earlier this year, the U.S. government approved the sale of $346 million in arms to strengthen Nigeria’s fight against insurgencies and criminal groups. More recently, however, Trump has threatened Nigeria with potential military action — and a halt to all aid and assistance — while alleging that Nigeria’s government is failing to rein in the persecution of Christians. Nigeria has rejected the claim.

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

Nigeria launched its Safe School Initiative in the aftermath of the Chibok mass abduction more than a decade ago. Today, the country is still struggling to stop kidnappings and protect its pupils.

Gunmen forced their way into the St. Mary Catholic Secondary School in Agwara, a town in eastern Nigeria, on November 21. Their gunfire ripped through the silence in the dormitories where pupils were still asleep. They then led the students, 303 in total, and 12 teachers away.

It was the second mass abduction in Nigeria in less than a week. Four days earlier, about two dozen girls were taken at gunpoint from a school in neighboring Kebbi state.

The mass abductions came after a warning by US President Donald Trump of military action against Nigeria over the alleged persecution of Christians in the country.

Nigeria has dismissed the claim, but it is facing multiple overlapping insecurity crises across its central and northern regions. Terrorists are laying siege to communities, carrying out mass abductions and kidnappings for ransom.

Ambitious initiative to protect Nigeria's schools

According to the Lagos-based SBM Intelligence consulting firm, at least 2.57 billion naira ($1.7 million, or €1.5 million) was paid to kidnappers between July 2024 and June 2025.

Schools are particularly soft targets. In the last 10 years, criminal gangs and Islamist militants have abducted no fewer than 1,880 pupils across Nigeria. Many were released, but some were killed.

The West African country is still scarred by the kidnapping of nearly 300 schoolgirls in northeastern Chibok in 2014 by Boko Haram militants. Some of the former students, most of whom were between the ages of 16 and 18 at the time, are still missing.

The government subsequently launched its Safe School Initiative (SSI) to protect schools, particularly those in high-risk areas, from terror attacks. Despite the initiative, which cost an initial $30 million, Nigeria is still struggling to stop mass abductions and protect children at schools.

Five hundred schools were supposed to benefit from the first phase, with 30 selected for the pilot project. The aim was to fortify schools with barbed-wire fences, deploy armed guards, provide staff training and counselling, and develop security plans and rapid response systems.

While a few SSI successes were recorded, including the provision of prefabricated classrooms and learning materials for children in displacement camps, momentum soon dipped. This was due in large part to a change in government in 2015, which many believe shifted priorities.

"It was meant to be the turning point in how Nigeria protects its schools," Seliat Hamzah, an inclusive education advocate in Nigeria, told DW. The big disconnect remains "weak, inconsistent implementation," she said.

"On paper, the framework covers everything; infrastructure, safety, emergency readiness, community engagement, teachers' training and the early warning system. But in many schools, especially in high-risk regions like the north, very little of these has materialized."

What's holding back school safety?

The implementation of the SSI has been slow. Four years ago, when the abductions at schools peaked again, particularly in the northwest region where criminal gangs prowl, authorities floated a four-year national financing plan for the SSI, with a total investment of 144.7 billion naira starting in 2023.

In 2021, an official assessment of roughly 81,000 schools found many to be vulnerable to attacks. So far, according to the National Safe School Response Coordination Center, only 528 of the country's schools are registered with it for the SSI.

Nigeria's school kidnappings highlight lawlessness in north 02:49

"It's quite apparent, because look at the widespread kidnappings that have been happening in recent times in schools across the country," said Hassana Maina, executive director of the Abuja-based ASVIOL Support Initiative, a civil society group that monitors school abductions.

"The gap is clear: the guidelines are there, but we don't have execution. The implementation is always patchy, monitoring is weak, and most interventions are one-off projects."

Analysts say coordination among Nigeria's security agencies, along with a funding crunch, is crippling the initiative. They note that the initiative's top-down approach prevented many communities from taking ownership of the SSI.

"Overreliance on security deployments without building community-based protections or early warning systems remains a major problem," said Maina. "Schools are always within a community, so we must ask questions [about] what the ideas are that we have about early warning systems, how we have built and fortified [them] into communities."

Can Nigeria's security initiative still work?

If the SSI is to live up to expectations, authorities would need to strengthen security measures in rural communities and bolster inter-agency coordination, said Hamzah.

"Community roles are still underutilized, and attackers continue to exploit the same long-standing vulnerabilities. So, we need to strengthen our security governance and improve coordination across agencies and bring communities to the center of the safety ecosystem."

Can Nigeria tackle recurring kidnapping patterns? 02:31

Confidence MacHarry, a senior analyst at SBM Intelligence, told DW: "There is no magic bullet to improving security in schools and protecting schools in the long term."

He warned that focusing solely on protecting critical infrastructure like schools without addressing the broader threats facing rural communities would amount to a mere drop in the ocean.

"If we want to improve protection and security in schools across Nigeria, we have to take a holistic approach because where criminal groups attack communities, no matter how strong the security in the schools is, it is going to psychologically discourage parents from wanting to send their kids to school."

Edited by: Benita van Eyssen

Abiodun Jamiu Abiodun Jamiu is a Nigerian freelance multimedia journalist.

Tens of thousands of voluntary or forced members of Boko Haram and the Islamic State in West Africa have surrendered over the past 10 years. Nigeria is drawing on transitional justice – a set of mechanisms used to confront legacies of mass violence in the interest of accountability, reconciliation and lasting peace – to help former fighters return to their communities and live alongside victims of the jihadist groups.

Issued on: 21/11/2025 - RFI

A tiny black dot moves across the sky over Bama, in north-eastern Nigeria. The roar of an engine grows louder, drowning out all other sounds in this town some 50 kilometres from Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State.

Kachalla, who is building a wooden door frame, pauses his hammering. "It's a helicopter," sighs the carpenter.

"In the Sambisa Forest, as soon as our leaders heard a helicopter flying overhead, they thought the army was watching them from the air. So it was every man for himself, we hid under the trees until the aircraft disappeared from view."

Kachalla looks up at the sky and watches the helicopter recede into the distance, then resumes his work.

'We were taught it was the right thing to do'

In 2020, this 30-something father left the ranks of Boko Haram. "I served as a soldier. At that time, we had no choice, we were forced to work for them. Otherwise, it was death if we refused to obey."

Kachalla joined the Association of the People of the Sunnah for Preaching and Jihad – the official name of Boko Haram, which was the name given to the group by local people in north-eastern Nigeria – in 2014.

He confesses to having committed acts of torture and bloody crimes within various factions, following orders including from the leader of Boko Haram, Abubakar Shekau, who was killed in 2021.

"I also did it of my own free will," Kachalla admits, "because we were taught that it was the right thing to do. And our leaders kept telling us that if we died, we would go to paradise."

'We hear a lot of whispered insults'

Today, Kachalla expresses his regrets only in private. He has resettled in Bama with his partner Bintugana, a former Boko Haram captive whom he "married" in the Sambisa Forest, and their two children – who were born in the Sambisa "sanctuary" led by Shekau.

Bintugana says Kachalla's carpentry skills have helped them build relationships in Bama. Despite knowing the couple's history, customers come to his workshop without fear.

Nevertheless, she believes their immediate neighbours still view them with contempt.

"We hear a lot of insults whispered by people, but it doesn't bother us because they can't physically fight us. At least our families don't reject us. That's why we don't want to go back to Sambisa," she explains.

In 2016, the Nigerian government launched Operation Safe Corridor to give members of Boko Haram and the Islamic State's West Africa Province (ISWAP – a breakaway faction aligned with the Islamic State group) the opportunity to disassociate themselves from these groups and reintegrate into society.

The initiative is supported by the Nigerian army and the country's security and intelligence agencies. At the same time, the state of Borno, the epicentre of the armed conflict, has also implemented a local approach: the Borno Model. Both have grown steadily alongside the mass defections from the Sambisa Forest, notably after the death of Shekau.

The Safe Corridor and Borno Model are two of the main formal mechanisms of transitional justice in the country. They are open to all repentant individuals – men, women and children – in north-eastern Nigeria.

"When we fled Boko Haram, we imagined the worst," recalls Kachalla. "Then I simply surrendered with my weapon. I was not mistreated. My family and I were officially registered."

Displaced by Boko Haram violence, the resourceful on Lake Chad’s shores try again

'Extremist ideology is deeply rooted'

Mustapha Ali has taken in dozens of former combatants with similar profiles to Kachalla over the past few years. A theology expert, he teaches in the Department of Islamic Studies at the University of Maiduguri.

He is also one of the pillars of the Imam Malik Centre, an educational institution for children from nursery to high-school age in the capital of Borno State, founded in the mid-1990s.

"This place is not just a place to learn about Islam," says Ali. "Our director, Sheikh Abubakar Kyari, was the first at the time to confront Mohammed Yusuf [the founder of Boko Haram] and his misinterpretations of the verses of the Koran that led to this extremist ideology."

Having witnessed the devastation wrought by Boko Haram in the Lake Chad basin, Ali also draws on his religious knowledge as an independent consultant for the El-Amin Islamic Foundation, a Nigerian NGO involved in deradicalisation programmes.

"I work with a maximum of 20 repentant individuals," he explains. "We focus on specific verses from the Koran. My team of facilitators and I meet with them at least 15 times. This is essential, because extremist ideology is deeply rooted in the minds of the adults and children we work with."

To start the process of reintegrating, Bintugana and Kachalla were transferred to a rehabilitation centre in Maiduguri. Bintugana was able to see her children while following a programme more focused on professional skills.

But for Kachalla and the other former combatants he was grouped with, their programme meant six months of living without any contact with the outside world.

"Every day we were given advice: how to live in peace with others, how to endure good and bad situations, how to be patient in all circumstances," he recalls.

Chita Nagarajan is an independent analyst of armed conflicts. For five years, she headed the Centre for Civilians in Conflict in north-eastern Nigeria. The organisation has carried out numerous mediations between communities and security forces, based on human rights principles.

"Reintegration, reconciliation and healing are not one-off events," she says. "They are long-term processes in which everyone needs support and assistance – the direct victims of violence, but also the indirect victims and even the perpetrators of that violence."

Since 2021, Bintugana and Kachalla have been learning how to live as a family again in Bama, surrounded by their loved ones. But theirs is a fragile peace, with the armed conflict that began in the Lake Chad basin in 2009 far from over.

This article has been adapted from a report in French by RFI's special correspondent in northern Nigeria, Moïse Gomis.