The origins of witches: Mystical malefactors have been with us across the millennia

'Beliefs in witchcraft are a reflection of a facet of human nature that we otherwise don’t want to acknowledge,' says anthropologist Manvir Singh

Author of the article:

National Post Staff

Publishing date:May 04, 2021 • May 4, 2021 •

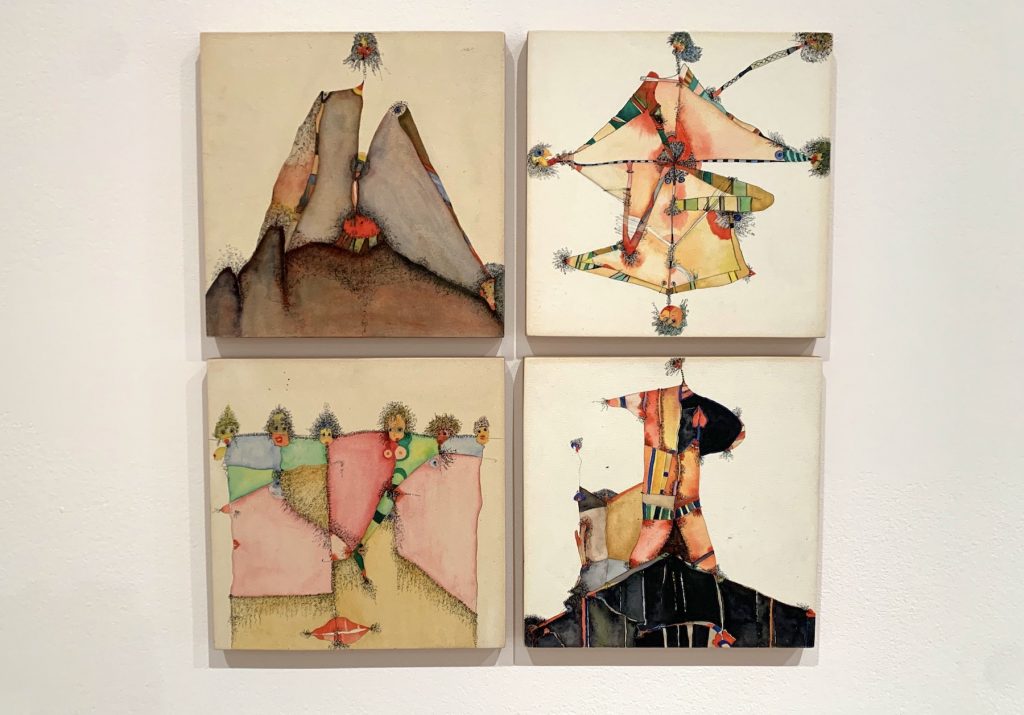

You will find that every human culture has stories about witches with supernatural powers who are existentially threatening and morally repugnant.

PHOTO BY WENDY LOVE/GETTY IMAGES/ISTOCKPHOTO

Witches get around, and not just on broomsticks.

Western culture has always bubbled with witch stories, from Endor and Sycorax to Sabrina the Teenage Witch and Cher of Eastwick.

But witches are not simply fantasies born of wild imaginations, invented by the Bible authors and William Shakespeare and so on, then copied like cartoons into the modern mass culture. They are not simply sexist tropes about old women, with their brooms and cauldrons (literally tools for cooking and cleaning) and their cat friends.

In fact, if you really look closely across cultures, as the anthropologist Manvir Singh has, you notice that beliefs about witchcraft tend to be directed at men and women in roughly equal measure.

More broadly, as Singh’s new peer-reviewed report in the journal Current Anthropology describes, you find that every human culture has stories about witches with supernatural powers who are existentially threatening and morally repugnant. The character is similar whether the source culture is the Yamba of Cameroon, the Santal of South Asia, or the Navajo of the American Southwest. Witches, Singh writes, “devour babies, fornicate with their menstruating mothers, and use human skulls for sports. They become bats and black panthers, house pythons in their stomachs, and direct menageries of attendant nightbirds. They plot the destruction of families and then dance in orgiastic night-fests.”

The details vary, but the character is the same. Human cultures always seem to come up with these ideas about mystical malefactors, notably witches with superpowers, but also sorcerers who have no supernatural powers of their own but rather learn and practice malicious spells, and people with the “evil eye” who can do harm just by looking or speaking.

In Singh’s theory, witches are part of human nature, placed there over the millennia by evolutionary dynamics.

To our evolved minds, witchcraft makes intuitive sense. So goes the theory

In an interview, he said his review of beliefs in witchcraft shows that they are not something peculiar that only used to happen in unique circumstances, such as the famous witch hunts in colonial New England and early modern Europe. Rather, they are expressions of human nature, features of our mind that reliably turn up in every human culture.

“Beliefs in witchcraft are a reflection of a facet of human nature that we otherwise don’t want to acknowledge,” Singh said.

Singh is an anthropologist at the Institute for Advanced Study at Toulouse, and recently completed doctoral research at Harvard University, in which he did field work among the Mentawai people of Indonesia. There, he was studying the local religion of a crocodile god who punishes people who do not share, and the activities of men who in another context might be called witch doctors, but are properly described as shamans.

In the peer-reviewed journal Current Anthropology, he reports the first results from a new research tool he created, the Mystical Harm Survey, which is used with the Human Relations Area Files, a massive scholarly data set that anthropologists use to compare ethnographic details about different modern human cultures.

In effect, he explains the origin of witches.

“We start with this puzzle of why human societies reliably develop these beliefs,” Singh said in an interview. The common approach to explaining this, known as functionalism, is basically to say that beliefs in harmful magic are an adaptation at the societal level that get reinforced because they promote co-operation. If everyone believes in witchcraft, this traditional theory goes, few people will harm others out of fear of reprisal. Fear of witches keeps everyone in line.

One problem with this theory, however, is that from an evolutionary perspective, a belief in witchcraft is incredibly costly. It destroys communal trust. To this day, people get killed for suspicion of witchcraft.

So, what if the source of witchery was closer to individual psychology? What if people look for compelling explanations of misfortune, and witchcraft is psychologically appealing, rather than socially useful?

Manvir Singh on Siberut Island, Indonesia, with the Mentawai people who believe in a punitive crocodile spirit. PHOTO BY LUKE GLOWACKI

The hypothesis Singh set out to test was that humans are endowed with psychological mechanisms that predispose them to think others are the cause of their misfortune. We are “adaptively paranoid,” and one result is a belief in witches.

His explanation is evolutionary, and refers to three cultural selective processes. The first is selection for intuitive magic. When people try repeatedly to influence the misfortune of others, they retain a sense for magical power. They remember stories about harmful magic, and as they do, they convince themselves it works, and that others use it. Over time, this is absorbed into culture and passed along in stories, fixing the idea in individual minds.

The second is selection for plausible explanations of misfortune. When things go bad, people look for someone to blame, and beliefs in magic give straightforward explanations, often much easier to grasp than the true ones. The crops did not fail because of chance weather or some unknown pest. They failed because a witch is trying to harm us. Which witch? Probably that weird old lady down the way, with the cats and the funny smelling soup pot.

The third is selection for demonizing narratives, in which mystical beliefs validate mistreatment of others.

“Separately, these selective schemes produce traditions as diverse as shamanism, conspiracy theories, and campaigns against heretics — but around the world, they jointly give rise to the odious and feared witch,” Singh writes in the report. “The three proposed schemes occur under different circumstances and frequently act independently of each other, separately producing superstitions, conspiracy theories, and propaganda. But they also interact and develop each other’s products, giving rise to beliefs in sorcerers, lycanthropes (werewolves), evil eye possessors, and abhorrent witches.”

Belief in witchcraft obviously will not stand up to modern scientific scrutiny, but humans have been around longer than science, and to our evolved minds, witchcraft makes intuitive sense. So goes the theory.

Even in contexts where people do not believe in or talk about witches, the same dynamics are evident and analogous beliefs emerge, Singh said, such as conspiracies about malicious governments or secret societies, which offer a conveniently broad explanation for specific misfortunes.

What makes Singh’s work a rare contribution to the science of witchcraft and sorcery is not just that he has catalogued these beliefs in “mystical harm” across diverse cultures, but that his theory also offers testable and falsifiable predictions about how these beliefs should change across circumstances.

His new research is turning to a larger database of religious history at the University of British Columbia, for which he will adapt his “Mystical Harm Survey,” to test these predictions. For example, on his theory, people should be more likely to believe in sorcerers as sorcery techniques become more “effective-seeming.” People should be more likely to blame misfortune on bad magic when they are already distrustful or persecuted, and more likely to demonize people as witches in times of stressful uncertainty. Mystical explanations also should be more likely in the absence of alternative explanations, or for particularly bad misfortune.

One curiosity is why good magic always seems to get second billing in witch stories. Singh’s view is that humans are predisposed to adaptive superstitions, but good events do not prompt the same bafflement as bad events, so in the long run, the bias leans toward suspicion and fear.