Issued on: 17/10/2021 -

Turkish philanthropist Osman Kavala faces a barrage of charges, including espionage and attempts to topple the state Handout Anadolu Culture Center/AFP

Istanbul (AFP)

Jailed without a conviction since 2017, Turkish philanthropist Osman Kavala says he feels like a tool in President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's attempts to blame a foreign plot for domestic dissent against his mercurial rule.

A gaunt and bearded intellectual who once patronised culture and the arts, the 64-year-old Kavala makes a striking foil for Erdogan, a promoter of political Islam who has governed Turkey with an increasingly iron fist since 2003.

While tens of thousands have been jailed or stripped of their jobs on tenuous charges since Erdogan survived a coup attempt in 2016, it is Parisian-born Kavala whose fate is creating particular tensions in Turkey's frayed ties with the West.

The Council of Europe, a human rights body Turkey joined in 1950, has warned it could launch the first infringement preceedings against Ankara if Kavala is not released by the end of the month.

Facing a barrage of alternating charges, including espionage and attempts to topple the state, Kavala does not expect to walk out of his Istanbul prison cell any time soon.

"I think the real reason behind my continued detention is that it addresses the need of the government to keep alive the fiction that the (2013) Gezi protests were the result of a foreign conspiracy," Kavala said in a written, English-language response to questions from AFP.

"Since I am accused of being a part of this conspiracy allegedly organised by foreign powers, my release would weaken the fiction in question and this is not something that the government would like."

Istanbul (AFP)

Jailed without a conviction since 2017, Turkish philanthropist Osman Kavala says he feels like a tool in President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's attempts to blame a foreign plot for domestic dissent against his mercurial rule.

A gaunt and bearded intellectual who once patronised culture and the arts, the 64-year-old Kavala makes a striking foil for Erdogan, a promoter of political Islam who has governed Turkey with an increasingly iron fist since 2003.

While tens of thousands have been jailed or stripped of their jobs on tenuous charges since Erdogan survived a coup attempt in 2016, it is Parisian-born Kavala whose fate is creating particular tensions in Turkey's frayed ties with the West.

The Council of Europe, a human rights body Turkey joined in 1950, has warned it could launch the first infringement preceedings against Ankara if Kavala is not released by the end of the month.

Facing a barrage of alternating charges, including espionage and attempts to topple the state, Kavala does not expect to walk out of his Istanbul prison cell any time soon.

"I think the real reason behind my continued detention is that it addresses the need of the government to keep alive the fiction that the (2013) Gezi protests were the result of a foreign conspiracy," Kavala said in a written, English-language response to questions from AFP.

"Since I am accused of being a part of this conspiracy allegedly organised by foreign powers, my release would weaken the fiction in question and this is not something that the government would like."

Philanthropist Osman Kavala says he does not expect to walk free any time soon Handout Anadolu Culture Center/AFP

- 'Dreyfus and the Rosenbergs' -

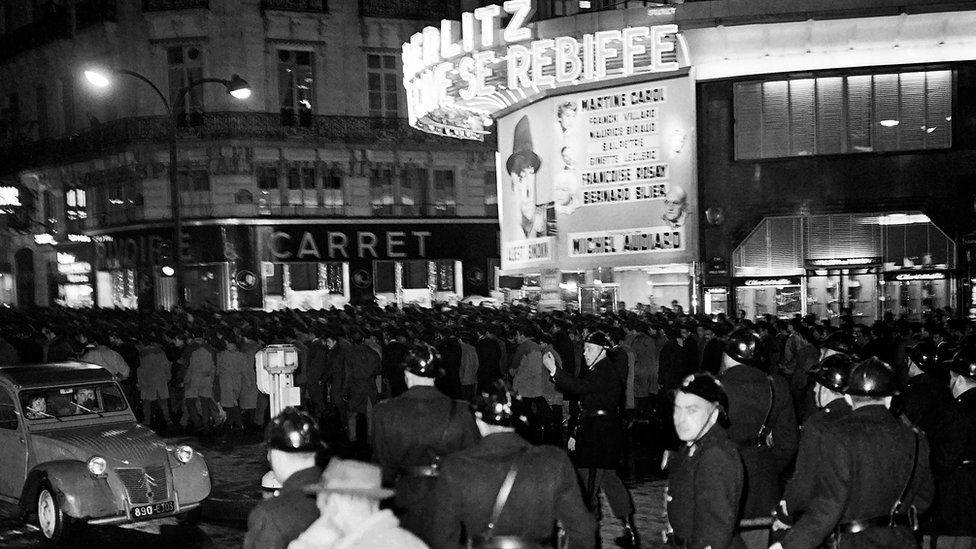

Kavala was referring to spontaneous rallies that broke out against plans to pave over a little park near Istanbul's Taksim Square that morphed into the first serious challenge to Erdogan's rule.

Some Turkey watchers see the 2013 protests, which were violently suppressed, as the original source of Erdogan's authoritarian streak.

Kavala was acquitted of the Gezi charges in February 2020, only to be re-arrested before he could return home and thrown back in jail over alleged links to the 2016 coup plot.

Well-versed in history, Kavala compares the current case against him to the treason charges faced by French captain Alfred Dreyfus in the late 1800s -- long discredited as an anti-Semitic plot -- and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, a US couple controversially executed for espionage in 1953.

"I suppose that the files on Dreyfus and the Rosenbergs were better prepared than mine," Kavala said.

- 'Dreyfus and the Rosenbergs' -

Kavala was referring to spontaneous rallies that broke out against plans to pave over a little park near Istanbul's Taksim Square that morphed into the first serious challenge to Erdogan's rule.

Some Turkey watchers see the 2013 protests, which were violently suppressed, as the original source of Erdogan's authoritarian streak.

Kavala was acquitted of the Gezi charges in February 2020, only to be re-arrested before he could return home and thrown back in jail over alleged links to the 2016 coup plot.

Well-versed in history, Kavala compares the current case against him to the treason charges faced by French captain Alfred Dreyfus in the late 1800s -- long discredited as an anti-Semitic plot -- and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, a US couple controversially executed for espionage in 1953.

"I suppose that the files on Dreyfus and the Rosenbergs were better prepared than mine," Kavala said.

Turkish philanthropist Osman Kavala was acquitted in 2020, only to be re-arrested before he could return home over alleged links to a 2016 coup plot

Handout Anadolu Culture Center/AFP

If convicted, he could be jailed for life without the possibility of parole.

- 'Political benefits' -

The Council of Europe has issued a final warning to Turkey to comply with a 2019 European Court of Human Rights order to release Kavala pending trial.

If not disciplinary proceedings could be launched and ultimately result in the suspension of Turkey's voting rights and even membership of the body.

But while such a step could further hurt Turkey's efforts to join the EU, Erdogan has given no indication that his views on Kavala have changed.

He calls him the "red Soros of Turkey" -- an agent of Hungarian-born US financier and pro-democracy campaigner George Soros -- a reference to Kavala's leftist views.

Kavala considers the Council of Europe his best hope for release.

"If the infringement procedure starts and if the damage this would cause is considered to outweigh whatever political benefits are expected from my continued detention, I might perhaps be released," he said.

If convicted, he could be jailed for life without the possibility of parole.

- 'Political benefits' -

The Council of Europe has issued a final warning to Turkey to comply with a 2019 European Court of Human Rights order to release Kavala pending trial.

If not disciplinary proceedings could be launched and ultimately result in the suspension of Turkey's voting rights and even membership of the body.

But while such a step could further hurt Turkey's efforts to join the EU, Erdogan has given no indication that his views on Kavala have changed.

He calls him the "red Soros of Turkey" -- an agent of Hungarian-born US financier and pro-democracy campaigner George Soros -- a reference to Kavala's leftist views.

Kavala considers the Council of Europe his best hope for release.

"If the infringement procedure starts and if the damage this would cause is considered to outweigh whatever political benefits are expected from my continued detention, I might perhaps be released," he said.

President Erdogan calls Kavala 'the red Soros of Turkey', an agent of Hungarian-born US financier and pro-democracy campaigner George Soros

Handout Anadolu Culture Center/AFP

- Eyeing 2023 -

Much of the focus in Turkey is shifting to June 2023, the last date by which Erdogan -- with approval ratings already at the lowest point of his career -- must call a general election.

Kavala, who has access to newspapers and a TV in his cell, watches the latest political developments with concern, questioning whether Erdogan is ready to accept a possible election defeat.

Erdogan and his ruling party "do not consider losing power as a normal consequence of economic problems and political competition," he said.

"They perceive a change of government as an extremely disturbing possibility.

"I am concerned that the political tension in the country might increase even more as the elections approach."

- Eyeing 2023 -

Much of the focus in Turkey is shifting to June 2023, the last date by which Erdogan -- with approval ratings already at the lowest point of his career -- must call a general election.

Kavala, who has access to newspapers and a TV in his cell, watches the latest political developments with concern, questioning whether Erdogan is ready to accept a possible election defeat.

Erdogan and his ruling party "do not consider losing power as a normal consequence of economic problems and political competition," he said.

"They perceive a change of government as an extremely disturbing possibility.

"I am concerned that the political tension in the country might increase even more as the elections approach."

Turkish philanthropist Osman Kavala says he believes his best hope for release is through the Council of Europe

Handout Anadolu Culture Center/AFP

Kavala's next court hearing is scheduled for November 26.

© 2021 AFP

Kavala's next court hearing is scheduled for November 26.

© 2021 AFP

What hope is left for Turkish political prisoner Osman Kavala?

The businessman and philanthropist has been acquitted and re-arrested on spurious charges. Is it possible to free him?

DAVID LEPESKA

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/W2B7JJ45FOO4XK3WECT7GONI7Q.jpg)

A poster featuring jailed businessman and philanthropist Osman Kavala in 2018. AFP

To describe Osman Kavala’s journey into the Turkish justice system as Kafkaesque would be paying a compliment to the great Czech novelist.

Authorities first detained the businessman and philanthropist at Istanbul’s Ataturk airport in October 2017 as he returned from the south-eastern city of Gaziantep, where he had begun work on a project to help Syrian refugees.

Two weeks later, he was officially arrested on suspicion of attempting to overthrow the government by leading the Gezi Park protests of mid-2013, and also on suspicion of attempting to overthrow the constitutional order by taking part in a July 2016 coup attempt. Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) tends to view the former as a sort of trial run for the latter, and labels anybody linked to either as a terrorist.

In February 2019, after 15 months of detention, Mr Kavala was finally indicted on the first count. A year later, an Istanbul court acquitted him of those Gezi-linked charges. But Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan quickly denounced that decision, and Mr Kavala was re-arrested and indicted in connection to the failed coup. He was acquitted on this charge the next month and again ordered to be released, but the court instead added a new charge of espionage, again linked to the failed coup, and Mr Kavala stayed in prison.

By this time the indictment against him ran to several hundred pages and hinged on random moments such as who he bumped into at an Istanbul restaurant. Despite the European Court of Human Rights (part of the Council of Europe, of which Turkey is a member) repeatedly finding no evidence to support the charges and calling for his immediate release, Turkish courts repeatedly approved Mr Kavala’s detention. In January 2021, an appellate court overturned the Gezi acquittal and that indictment was added to his espionage case.

The latest twist came this August. A Turkish court linked Mr Kavala’s Gezi-espionage case to a separate trial involving Carsi, the leading fan group of Istanbul football club Besiktas. Carsi members played a key role in the Gezi protests, but like Kavala they had previously been acquitted of any Gezi-linked crimes.

If all this has left you dizzy, you are not alone. Amnesty International has called Mr Kavala’s case a “shocking disregard for fair trial procedures”. Yet this three-legged trial resumed at Istanbul’s vast hall of justice last Friday, where a panel of judges called, yet again, for Mr Kavala to remain in custody.

From his cell in Silivri prison, 40km west of Istanbul, the prisoner issued a searing statement. “What is striking about the charges brought against me is not merely the fact that they are not based on any evidence. They are allegations of a fantastic nature based on conspiracy theories overstepping the bounds of reason,” he said, adding that many of his co-defendant Besiktas fans had no idea who he was. “The joinder with the Carsi case makes this even more surreal. When asked, ‘Do you know Osman Kavala?’ a supporter asked, ‘Which club does he play for?’”

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/UYPKYIS2UBCRELQBNLEFVQMGLM.jpg)

2013's Gezi Park protests in Istanbul were a seminal moment for popular movements opposed to Turkey's President. AFP

If Kavala's case has left you dizzy, you are not alone

Few could have foreseen all this for Mr Kavala, who turned 64 last week. Having built their fortune in tobacco, his family moved from the Greek port city of Kavala to Istanbul in the population exchange of 1923. When his father died in 1982, Osman broke off his doctorate studies in New York City to take the reins of the family business.

He expanded into publishing, then environmental and civic activism. He founded Anadolu Kultur, an organisation that develops civic collaborations, such as a vast arts centre in the majority-Kurdish city of Diyarbakir, and cultural preservation projects for Yazidis, Armenians and other minorities.

In 2008, he founded a Turkish chapter of the Open Society Foundation, the global pro-democracy organisation of Hungarian-born billionaire George Soros. It is this move, in addition to his prominent place among the country’s liberal elite, which seems to have put Mr Kavala in the authorities’ crosshairs. Turkey’s President has described him as a terror financier backed by “the famous Hungarian Jew Soros”. Asli Aydintasbas of the European Council on Foreign Affairs has described Mr Kavala’s case as a personal “vendetta” that is “unnecessarily cruel”.

Vendettas do make headlines. A recent study found more than 1,700 news articles on Mr Kavala's case over the past four years, in more than 40 countries. Yet his is merely the most prominent of hundreds of thousands of ongoing prosecutions in Turkey linked to the failed 2016 coup, the Gezi protests or other activist movements. Turkish courts are overwhelmed with such cases, and since thousands of judges were dismissed in post-coup purges, many are overseen by young, inexperienced judges.

Most appear to be susceptible to political pressure and thus lean toward guilty verdicts. As a result, Turkey’s prison population is today by far the highest among the 47 members of the Council of Europe. Nearly 1 per cent of Turkish citizens are in prison, compared to less than 0.27 per cent across Europe. The number of university-graduate prisoners has also increased sharply, from 4,400 in 2012 to more than 20,000 in 2019, suggesting increased politicisation. And despite a troubled economy, Turkey’s government has, since the failed 2016 coup, spent $1.4 billion on more than 130 new prisons, nearly doubling incarceration capacity from 180,000 to 320,000.

Next week, Mr Kavala will mark four years of incarceration, despite never having been convicted of a crime. The chances that he might soon gain his freedom remain slim, but one recent development may boost those odds. The Council of Europe last month warned that if Turkey fails to heed the European Court of Human Rights’ legally binding calls to release Mr Kavala, it will begin infringement proceedings.

The Council’s harshest enforcement mechanism was created in 2010 and could lead to the suspension of Turkey’s membership. It has been used just once before. In late 2017, the Council launched proceedings against Azerbaijan, another member state, for its detention of politician Ilgar Mammadov. Eight months later, Mr Mammadov was a free man.

Published: October 10th 2021, 8:00 AM

:quality(70)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/thenational/52b1a973-24a3-4f16-bf80-6106a7da2d0d.png)

David Lepeska a veteran journalist who has reported widely across the region and contributed to top outlets including the New York Times, the Guardian, and the Atlantic, is the Turkish and Eastern Mediterranean affairs columnist for The National

MORE FROM DAVID LEPESKA

Turkey could be on the cusp of a new era

Turkey and Russia zero in on Idlib

Why Turkey and Greece are at it again

The businessman and philanthropist has been acquitted and re-arrested on spurious charges. Is it possible to free him?

DAVID LEPESKA

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/W2B7JJ45FOO4XK3WECT7GONI7Q.jpg)

A poster featuring jailed businessman and philanthropist Osman Kavala in 2018. AFP

To describe Osman Kavala’s journey into the Turkish justice system as Kafkaesque would be paying a compliment to the great Czech novelist.

Authorities first detained the businessman and philanthropist at Istanbul’s Ataturk airport in October 2017 as he returned from the south-eastern city of Gaziantep, where he had begun work on a project to help Syrian refugees.

Two weeks later, he was officially arrested on suspicion of attempting to overthrow the government by leading the Gezi Park protests of mid-2013, and also on suspicion of attempting to overthrow the constitutional order by taking part in a July 2016 coup attempt. Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) tends to view the former as a sort of trial run for the latter, and labels anybody linked to either as a terrorist.

In February 2019, after 15 months of detention, Mr Kavala was finally indicted on the first count. A year later, an Istanbul court acquitted him of those Gezi-linked charges. But Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan quickly denounced that decision, and Mr Kavala was re-arrested and indicted in connection to the failed coup. He was acquitted on this charge the next month and again ordered to be released, but the court instead added a new charge of espionage, again linked to the failed coup, and Mr Kavala stayed in prison.

By this time the indictment against him ran to several hundred pages and hinged on random moments such as who he bumped into at an Istanbul restaurant. Despite the European Court of Human Rights (part of the Council of Europe, of which Turkey is a member) repeatedly finding no evidence to support the charges and calling for his immediate release, Turkish courts repeatedly approved Mr Kavala’s detention. In January 2021, an appellate court overturned the Gezi acquittal and that indictment was added to his espionage case.

The latest twist came this August. A Turkish court linked Mr Kavala’s Gezi-espionage case to a separate trial involving Carsi, the leading fan group of Istanbul football club Besiktas. Carsi members played a key role in the Gezi protests, but like Kavala they had previously been acquitted of any Gezi-linked crimes.

If all this has left you dizzy, you are not alone. Amnesty International has called Mr Kavala’s case a “shocking disregard for fair trial procedures”. Yet this three-legged trial resumed at Istanbul’s vast hall of justice last Friday, where a panel of judges called, yet again, for Mr Kavala to remain in custody.

From his cell in Silivri prison, 40km west of Istanbul, the prisoner issued a searing statement. “What is striking about the charges brought against me is not merely the fact that they are not based on any evidence. They are allegations of a fantastic nature based on conspiracy theories overstepping the bounds of reason,” he said, adding that many of his co-defendant Besiktas fans had no idea who he was. “The joinder with the Carsi case makes this even more surreal. When asked, ‘Do you know Osman Kavala?’ a supporter asked, ‘Which club does he play for?’”

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/UYPKYIS2UBCRELQBNLEFVQMGLM.jpg)

2013's Gezi Park protests in Istanbul were a seminal moment for popular movements opposed to Turkey's President. AFP

If Kavala's case has left you dizzy, you are not alone

Few could have foreseen all this for Mr Kavala, who turned 64 last week. Having built their fortune in tobacco, his family moved from the Greek port city of Kavala to Istanbul in the population exchange of 1923. When his father died in 1982, Osman broke off his doctorate studies in New York City to take the reins of the family business.

He expanded into publishing, then environmental and civic activism. He founded Anadolu Kultur, an organisation that develops civic collaborations, such as a vast arts centre in the majority-Kurdish city of Diyarbakir, and cultural preservation projects for Yazidis, Armenians and other minorities.

In 2008, he founded a Turkish chapter of the Open Society Foundation, the global pro-democracy organisation of Hungarian-born billionaire George Soros. It is this move, in addition to his prominent place among the country’s liberal elite, which seems to have put Mr Kavala in the authorities’ crosshairs. Turkey’s President has described him as a terror financier backed by “the famous Hungarian Jew Soros”. Asli Aydintasbas of the European Council on Foreign Affairs has described Mr Kavala’s case as a personal “vendetta” that is “unnecessarily cruel”.

Vendettas do make headlines. A recent study found more than 1,700 news articles on Mr Kavala's case over the past four years, in more than 40 countries. Yet his is merely the most prominent of hundreds of thousands of ongoing prosecutions in Turkey linked to the failed 2016 coup, the Gezi protests or other activist movements. Turkish courts are overwhelmed with such cases, and since thousands of judges were dismissed in post-coup purges, many are overseen by young, inexperienced judges.

Most appear to be susceptible to political pressure and thus lean toward guilty verdicts. As a result, Turkey’s prison population is today by far the highest among the 47 members of the Council of Europe. Nearly 1 per cent of Turkish citizens are in prison, compared to less than 0.27 per cent across Europe. The number of university-graduate prisoners has also increased sharply, from 4,400 in 2012 to more than 20,000 in 2019, suggesting increased politicisation. And despite a troubled economy, Turkey’s government has, since the failed 2016 coup, spent $1.4 billion on more than 130 new prisons, nearly doubling incarceration capacity from 180,000 to 320,000.

Next week, Mr Kavala will mark four years of incarceration, despite never having been convicted of a crime. The chances that he might soon gain his freedom remain slim, but one recent development may boost those odds. The Council of Europe last month warned that if Turkey fails to heed the European Court of Human Rights’ legally binding calls to release Mr Kavala, it will begin infringement proceedings.

The Council’s harshest enforcement mechanism was created in 2010 and could lead to the suspension of Turkey’s membership. It has been used just once before. In late 2017, the Council launched proceedings against Azerbaijan, another member state, for its detention of politician Ilgar Mammadov. Eight months later, Mr Mammadov was a free man.

Published: October 10th 2021, 8:00 AM

:quality(70)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/thenational/52b1a973-24a3-4f16-bf80-6106a7da2d0d.png)

David Lepeska a veteran journalist who has reported widely across the region and contributed to top outlets including the New York Times, the Guardian, and the Atlantic, is the Turkish and Eastern Mediterranean affairs columnist for The National

MORE FROM DAVID LEPESKA

Turkey could be on the cusp of a new era

Turkey and Russia zero in on Idlib

Why Turkey and Greece are at it again

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/7T5F4YQYEQBVKNU5YZSQQ5VIV4.jpg)

:quality(70)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/thenational/0c776a17-4aec-4e4c-95b2-489017fb7875.png)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/DWZPSM45VZFT4FXEGOSQOQ6H34.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/TLNWH3VCLUPIGEDXWWQ2BPM4FA.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/4C6FCDMEQQAMEO2KMDIFBMCW7A.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/PSWKK37PALBM4EIONZSRLOMAQ4.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/BGTZGGZXHTWHB5LUSHSSUCNXOY.jpg)

:quality(70):focal(3967x1565:3977x1575)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/4WEQMWNPQELRFVRFLGORMJMIL4.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/VNO2BRIXQPWAGRTTH5VRM7CORQ.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/A655IS7LE7CBJDHTLBCSQ3PECY.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/AA3W34T6GLCYHWLVD4U6AJX7VM.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/ORKIV6RZWXCTHDT2LULCBXX52Y.jpg)

:quality(70):focal(-5x-5:5x5)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/2QTOLXASPGRVTESHZOUOOFAVXU.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/2GA3JA4XNUBJ3ED5NQPOGVHYD4.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/Y6OMWWFJ2RUGJ7BX7VUODWMUHI.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/H5QVJB3OO6R3LSF2MVIGSDQ7PY.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/2OSCRGMATC2YADRKXO262UH22Q.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/PK5RA4XJXRTJYVHDXELJ5KEWII.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/7NPXZFE37KX2JTSHQQ2C3LY53M.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/EHIYVX3Z7MM2JRX6BQCTBZJZ3A.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/ZL2IKALB477XCWAW4SROOWVVVA.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/OWEN7VPWUWMRNOFDP4XAXALVJQ.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/EQZOVI6YX5FFTZZ6ZU2A26NATQ.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/3TKFPCDS5EUDJ2BFINAUXOQ4ZQ.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/FIKXSWMFZDAWX2VPFWTO7Q4CXQ.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/KI6Z52Y6FLJW6QV5XKDZZB2FBI.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/NU6DFGNXKO3TQUEQ4ZVKISD7NU.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/IF32D33BQXT3TSLTPR2L6DYDGI.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/MLCJQLE7VUYRHC26K2EQX7E6GA.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/S6SJ6OJDAZTEURIJNOBVDXSQRE.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/6QEELNRZNBQXEHLIHZHRL67PII.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/LHPWETGHMFWSDO6NREKGZ4AFZ4.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/2S6LMH7DVOPOTRENJT6445XDVI.jpg)